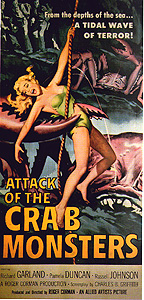

Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957) **½

Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957) **½

A lot of folks who were kids during the late 1950’s will tell you that Attack of the Crab Monsters scared the crap out of them. It’s hard to believe that this could be on the basis of the most commonly circulated promotional still from the film, showing the whole of its fifteen-foot papier-mâché crab sitting inert on the sandy floor of a cave somewhere outside of Los Angeles. But when producer/director Roger Corman commissioned the script for this movie from frequent collaborator Charles Griffith, he specifically instructed that every scene of its hour-long running time be suffused with either action or suspense, and the remarkable truth is that Griffith came pretty close to delivering on the order. Furthermore, Corman wisely shot most of the monster scenes as a succession of tight close-ups, disguising the worst shortcomings of the rather pathetic giant crab. Attack of the Crab Monsters still suffers from uneven acting, irritating comic relief, and a monster origin story consisting of some of the most incomprehensible pseudoscientific gibberish ever uttered, but it’s a remarkably streamlined and fairly effective film— perhaps the earliest to give some indication of what its director would prove himself capable of during the following decade.

The setting is a small island in the South Pacific, not far from the site of a recent US Navy H-bomb test-firing. The island is well placed to have received the worst of the fallout from the explosion, and the military is therefore eager to have some scientists look the place over. The first team they sent vanished without a trace, however; the working hypothesis is that all of them must have been out on the beach just in time to get carried away when a typhoon blew up out of nowhere right on top of the island, but nobody really knows. Regardless, the project is too important to be abandoned, so now nuclear physicist Karl Weigand (Teenage Caveman’s Leslie Bradley) has arrived with four other scientists, a radio technician, and a pair of Seabee demolitions experts to continue the work. Assisting Weigand are meteorologist Jules Deveroux (Mel Welles, from Chopping Mall and The Little Shop of Horrors), geologist Jim Carson (Richard H. Cutting, of Monster on the Campus and The Monolith Monsters), and biologists Dale Drewer (Richard Garland, from Mutiny in Outer Space and Panic in the Year Zero!) and Martha Hunter (The Undead’s Pamela Duncan). The radio man is Hank Chapman (Russell Johnson, of This Island Earth and The Space Children), and the Seabees are Seamen Jack Sommers (Tony Miller) and Ron Fellows (Beach Dickerson, from War of the Satellites and Creature from the Haunted Sea).

The assignment gets off to an alarming start when one of the sailors under the command of Ensign Quinlan (Ed Nelson, from She-Gods of Shark Reef and The Brain Eaters) dies in a puzzling accident while ferrying the scientists’ supplies ashore from the floatplane that brought them in. The unfortunate man falls out of Quinlan’s motor launch in about five feet of water, and almost immediately begins struggling as if entangled with something. By the time one of the other men gets him back aboard the boat, he has been cleanly decapitated! There is no sign of sharks, or of any other species of marine life that ought to be capable of inflicting such damage— in fact, the only living things immediately visible on the island or in its environs are seagulls and land crabs. And as if the decapitation weren’t enough inexplicable misfortune for one morning, Quinlan’s plane explodes just moments after takeoff, killing everybody aboard.

Nevertheless, Weigand and the others have a job to do, and they’re stuck on the island for the immediate future in any case. They set up in the same cottage where their predecessors’ had made their homes and laboratories, and discover the previous team’s journals. The material in those journals almost certainly rules out the Navy’s favored explanation of the vanished scientists’ fate, for the last entry breaks off in the middle of describing an experiment. Whatever became of them, they clearly didn’t get taken unawares by the typhoon. The notebook also reveals that the first group had discovered something very strange during their investigations— a mass of tissue cytologically akin to earthworm flesh, but of such size that only the largest of deep-sea tube worms could possibly account for it. What’s more, that mysterious hunk of worm meat was impossible to cut, not because it was too tough to be penetrated by a scalpel, but because any incision made in it immediately resealed itself behind the passing blade. Neither of Weigand’s biologists have ever heard of such a thing.

The island itself proves equally mysterious. Though it is not known to lie anywhere near either a fault-line or a volcanic plume, it is subject to frequent seismic tremors, which pare away its shores and open great rents in its interior. These tremors are invariably preceded by what sounds like either nearby thunder or a series of powerful explosions, but there have been no storms, and the two demolitionists can account for all of their dynamite and blasting caps. Meanwhile, both Hunter and Carson are convinced that they hear human voices calling to them in the night. These aren’t just any voices, either, but those of the men whose work they have come to the island to finish. It’s a small island, and the Navy already searched it thoroughly for survivors— surely there’s no chance that any of the earlier researchers could have remained there unnoticed! Then the members of Weigand’s team begin disappearing themselves. Jim Carson is the first. He injures his leg while exploring a pit created by one of the curious earthquakes, and is unable to climb back out. The rest of the team tries to reach him through the sea caves to which the pit connects, but although they repeatedly hear Carson calling to them, the would-be rescuers can find no sign of him, alive or dead. Next, something absconds with Sommers and Fellows, together with most of their explosives. (Hot damn! This makes twice in as many years that a screenwriter working for Roger Corman has had the good taste to kill off the comic relief!) Then some enormous beast attacks the cottage while Drewer and Hunter are alone inside it. The hulking intruder spares the scientists, but destroys Hank Chapman’s radio rig. Corman and Griffith go to great lengths to play coy with the identity of the threat, but I seriously doubt that anyone who’s seen this movie in the 50 years since its original release has been even a tiny bit surprised that it turns out to be a pair of colossal land crabs, mutated into monsters by the radioactive fallout. These aren’t just any plus-sized crustaceans, though. By eating the heads of their victims, they are able to absorb those people’s knowledge and consciousness. In addition, the radiation has caused the molecules of the creatures’ bodies to de-cohere somehow; you might say they aren’t so much crabs anymore as two huge, undifferentiated masses of fundamental particles, held together by crab-shaped electromagnetic fields. Not only are they now virtually invulnerable to attack (imagine trying to kill a swimming pool with bullets or blades), they can also channel some of that electrical energy into massive, lightning-like discharges capable of triggering severe but highly localized earth tremors. I believe we can safely say that even a garage-sized steam pot and a barrel of lemon butter aren’t going to get the job done.

If Attack of the Crab Monsters has one glaring weakness (apart, I mean, from the underwhelming monsters), it’s the increasingly desperate pretense that there’s some kind of secret regarding what the scientists are facing on the island. I appreciate the value that Corman placed on suspense, and I applaud his and Griffith’s success in generating a certain amount of it. But let’s be realistic here— this movie is called Attack of the Crab Monsters. We know what the menace is before we’ve even bought a ticket or taken the videotape out of the shrink wrap! Our first look at the creatures isn’t that big a revelation, and treating it as if it were is an insult to the audience’s intelligence. It would have been much better to aim for a more forthright form of suspense, peppering the first act with glimpses of a pincer here, an antenna there, and taking the attack on the biologists in the cottage as the occasion for showing us the titular beasties in all their glory for the first time. Otherwise, Attack of the Crab Monsters is a cut above the average low-budget critter flick of the 1950’s. Unlike practically everything else of its time and type, it makes a good-faith effort to be scary, and Corman demonstrates a great deal of imagination in finding shortcuts and work-arounds to make up for the money he didn’t have. It’s a pretty audacious move trying to make a film involving a disintegrating island on a $70,000 budget, and while I can’t say I ever really bought into the conceit (or indeed, into the conceit that the actors were even on an island in the first place), I got a kick out of watching the filmmakers scramble to suggest what they couldn’t afford to show. Corman obviously still had a bit of growing yet to do before he was ready to give the world X! or The Pit and the Pendulum, but this is nevertheless a great leap forward from the likes of Swamp Women.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact