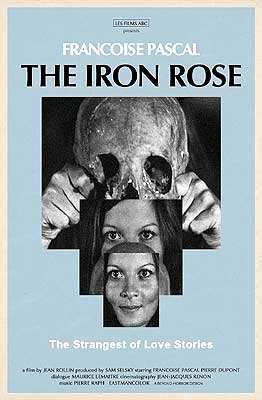

The Iron Rose /La Rose de Fer (1973) ***½

The Iron Rose /La Rose de Fer (1973) ***½

Now that we’ve seen the beginning of Jean Rollin’s career as a pornographer, let’s take a step back, and have a look at the reason why he got involved with porn in the first place. Understandably weary of the bloodsucking undead after Requiem for a Vampire, Rollin sought to stretch out into new territory. At the same time, he was growing eager to conduct another experiment along the lines of The Nude Vampire— but whereas that film was designed to embody the concept of mystery, Rollin wanted his next project to be driven purely by atmosphere. Perhaps he too had noticed that the movies he’d made thus far were at their best when they were basking in the mood of an especially evocative location. He discovered the perfect place on a scouting mission to Amiens with his cinematographer friend Jean-Jacques Renon, when the two men got themselves lost in that city’s famous Madeleine Cemetery for some 20 minutes as the sun went down. By the time they blundered their way to the exit, both of them were half-convinced that they’d become trapped in some Neverland of the dead. With the help of Maurice Lemaitre, Rollin extrapolated his eerie experience into a screenplay and got to work, shooting in the very boneyard that had inspired him.

On the surface, The Iron Rose looked like it would be too cheap not to turn a profit. The project called for no sets, no special effects, no props that couldn’t be bought at a corner store, no costumes so unusual that they couldn’t be rented somewhere, and only two actors (a crewmember pulling double duty would suffice for any of the small supporting parts). No problem, right? But Amiens is far enough away from Paris that Rollin and company couldn’t just drive out to the cemetery every morning and come home every night— or vice versa, since most of The Iron Rose was filmed after dark. Producer Sam Selsky therefore had to arrange lodging in town for everybody, and all those hotel bills quickly multiplied the expected cost of the picture. Worse yet, the finished product found itself torn between the countervailing prejudices of the horror and art film audiences. The latter, who might have appreciated the experiment at the movie’s core if they’d allowed themselves to, were not prepared to give any fright film an even break unless it could cover itself with the respectability of age. And the former had no patience for anything with so attenuated a story, or with so little violence and sexual content. The Iron Rose was shown almost nowhere, and provoked mass walkouts wherever it did play. Five years after Rollin’s success de scandal with The Rape of the Vampire, French moviegoers had had enough of him. For the rest of the decade, the only way Rollin could raise money for the movies he wanted to make was to accept work-for-hire gigs in the skin flick market (generally hiding behind the pseudonym Michel Gentil).

The Iron Rose of the title is a piece of ornamental metalwork such as might adorn the fences or handrails of a cemetery; the first time we see it may not actually be happening in objective reality. A girl whom we will later come to know as Karine (Françoise Pascal, of School for Sex and Keep It Up Downstairs) finds it washed up on the beach where she’s taking a stroll (Is it that beach on the outskirts of Dieppe with the snaggly old jetties? What do you think?), and is disturbed by it for some reason. She tosses it into the surf, and watches until she’s satisfied that the waves have carried it away again. What seems unreal about that, you ask? Well, nothing at the moment. But once you’ve seen the end of the film, the opening scene starts to look like a flash-forward set inside Karine’s head, in which the rose represents something she’d prefer not to remember.

Anyway, we next encounter Karine as a guest at a wedding reception in a crummy neighborhood in Amiens; I gather she’s a friend of the bride. One of the groomsmen (Hugues Quester, from The Flesh of the Orchid)— we never do learn his name— stands up to recite an ironically depressing poem in honor of his friend’s farewell to bachelorhood, gazing intently across the room at Karine all the while. Later, he tells her it was the only way he could think of to get her attention. The guy also says that he likes to go bike-riding on Sundays, and invites Karine to join him the following day. She thinks that sounds like fun, and agrees to meet him at the train station at 11:00 in the morning.

Strictly speaking, the pair seem to do more making out than bike-riding, but no matter. At some point, they do mount up and get moving, although Rollin has the decency not to ask us to watch much of that. Eventually, in the late afternoon, the guy leads Karine to stop outside Madeleine Cemetery. Neither of them have ever been inside its walls, but to judge from the jungle of huge, old trees visible over them, it should be a fine place to eat the picnic supper they packed. Karine’s date doesn’t fully process her reluctance to enter the graveyard, and he’ll keep right on not processing it throughout the rest of the day. He, you see, is a materialist, to whom the cemetery is nothing but a restful pocket of countryside which the city he hates has permitted to take root inside it. The centuries’ worth of overgrown tombs, meanwhile, are merely monuments to the folly of those who believe that a statue, a cross, or a slab of marble will suffice to make the future remember. But to Karine, the graveyard seems a nexus of malign power. She’s not saying she believes in ghosts, mind you, but she’s not saying she doesn’t believe in them, either. Besides, the few living people the couple see during their explorations are creepy enough all by themselves: the cross-dressing clown (Paris Porno’s Mireille D’Argent, who also played an inexplicable clown in The Demoniacs), the fop in the Dracula cape (Requiem for a Vampire’s Michel Delesalle), the sour-faced man with the accusatory stare (Rollin himself), the lady in black who lays flowers on what feels like half the graves in the cemetery (unsung Rollin sidekick Natalie Perrey, who did everything from typing up scripts to serving as Rollin’s assistant director during their long association). The most disconcerting thing of all, though, is just the way the graveyard’s size, age, and overgrowth combine to filter out any evidence that Amiens even exists. It might feel like being out in the country to Karine’s new boyfriend, but to her, it feels like being in the Twilight Zone.

Nevertheless, Karine lets herself be persuaded not merely to eat supper in the necropolis, but also to sneak down into one of the underground mausoleums to have sex. The sun is on its way down by the time they finish, and the light is gone altogether once they find their way to what they think is the main path through the cemetery. Either they’re mistaken about that in the first place, though, or they take a turnoff without realizing it, because soon the lovers are totally lost. Neither one reacts well to the situation. Karine grows more and more hysterical, while her boyfriend grows more and more furious with her hysterics. When their efforts to find the caretaker’s cottage turn up some kind of charnel workshop instead, Karine snaps completely. Her guy doesn’t recognize that at first, though, because the main outward symptom of her snapping is a sudden calm. Inside, however, Karine has decided that she likes the cemetery after all. In fact, she now thinks she and her date should take up residence there, as it were…

This is going to sound like damningly faint praise, but I mean it in all sincerity: The Iron Rose is the best movie I’ve ever seen in which absolutely nothing happens. I don’t recommend it for everyone— shit, I don’t recommend it for myself ten years ago— but if Rollin’s notion of a horror movie that works by atmosphere alone sounds to you like anything other than a fool’s errand, you ought to give it a try. At its best, it reminds me a little of Long Weekend, insofar as it’s about a couple under trying circumstances coming unhinged with deadly results. But in The Iron Rose, there’s no external threat to the protagonists whatsoever, and Rollin never remotely suggests that there might be. There’s just an oppressively spooky place and two people whose psyches are not up to dealing with it— there is literally nothing to fear but fear itself. Many if not most viewers are going to find that boring, and at the very least, The Iron Rose demands that you lay aside all preconceptions of what a horror movie is supposed to do or be. In my case, it may have been the very fact of Rollin’s involvement that opened me up to this movie’s contrarian approach. His early vampire films taught me that all bets are off when he’s running the show, so my attitude going in was basically, “Okay, Jean— what fucked-up, screwball thing have you got for me this time?”

If you’ve seen any of Rollin’s other movies (well, maybe any of them except Zombie Lake), you’ve already got some idea what makes The Iron Rose tick. Think of the crypt and the ruined castle in Lips of Blood, the condemned chateau in The Rape of the Vampire, the torture gazebo in Schoolgirl Hitchhikers, the mudflats strewn with shipwrecks in The Demoniacs. Most of all, think of that beach of his in practically everything. Think about how he and his cinematographers turn the moods of those places into something virtually tangible, and make of them the foundations on which the rest of the movies stand. It’s the same thing here, only the mood of Madeleine Cemetery isn’t just the foundation for The Iron Rose. In this film, that mood is the entire edifice. And while it might seem unlikely that any mere location could be up to that challenge, this graveyard is nothing to dismiss with an adjective like “mere.” If you wanted a place to represent the concept of the past as a living force, bending the present to its will, you couldn’t do much better than the Amiens necropolis. And since that’s really just a very abstract way of saying “haunted,” I think you can understand why the cemetery is so perfectly suited to this project. As always, though, Rollin’s genius as a location scout is only part of the story. The other part is that he and Renon knew how to make you feel like you’re there, right alongside the doomed lovers.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable focusing on less reputable side of French cinema. Click the banner below to read the rest of the gang’s contributions.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact