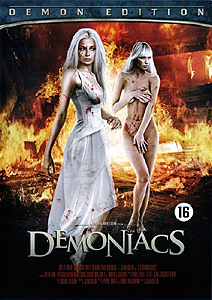

The Demoniacs / Demoniacs / Curse of the Living Dead / Les Demoniaques (1974) **½

The Demoniacs / Demoniacs / Curse of the Living Dead / Les Demoniaques (1974) **½

Since I began this crash course in the early works of Jean Rollin by saying that he was more than just the Sexy Vampire Movie Guy, I probably ought to review something of his that isn’t a sexy vampire movie. The Demoniacs should do the trick. This is one of Rollin’s least classifiable horror films. Although it falls broadly within the occult horror category that was reaching its peak of international popularity in 1974, The Demoniacs is not a devil-cult movie or a possession story or an “Oh no! My baby is the Antichrist!” tale. Instead, it’s more of a supernaturally enhanced, period-piece rape revenge picture, and the devil here is one of the good guys. In crass High Concept terms, it’s a bit like “Sugar Hill meets I Spit on Your Grave on the set of Night Creatures.”

Somewhere off the Belgian coast, in what we’d identify as powdered wig days if any of these characters had the social standing to pull off that affectation, sits a little island where a band of pirates make their lair. Actually, it seems the place isn’t always an island. It and a few other plots of land like it are surrounded by rocky shoals that are fully submerged only at high tide; when the tide is out, they become effectively part of the mainland. That unusual topography explains how such a small crew— just the captain (John Rico, from Blood Orgy of the She-Devils), Le Bosco (Willie Braque, of Schoolgirl Hitchhikers and Fly Me the French Way), and Paul (Paul Bisciglia, from House of 1000 Pleasures and Lips of Blood), plus the captain’s sexually rapacious lover, Tina (Joelle Coeur, of French Undressing and Erotic Diary of a Lumberjack)— can get any proper buccaneering done. Obviously the four of them aren’t going to be storming any freighters by themselves to put their crews to the sword, and modern business practices like outsourcing and subcontracting haven’t been invented yet. Instead, the pirates set bonfires after nightfall on their nastiest stretch of beach in the hope of luring passing ships onto the shoals. Then they board the wrecks as the tide recedes, finish off any survivors, and help themselves to the cargo. Needless to say, the captain and his followers are not a popular bunch in the nearest mainland settlement, but the people there are too well cowed to give them any trouble.

One night, the pirates’ usual activities yield unusual results, in that the survivors prove as interesting as the goods salvageable from the wreck. Washed up along with a chest containing fine clothes and jewelry are two lovely, twenty-ish blonde girls (Lieva Lone and The French Love’s Patricia Hermenier). Naturally they’ll have to be killed sooner or later, just like any other witness to the gang’s crimes, but there’s no reason the pirates shouldn’t have some fun with them first. The castaways are raped and beaten pretty much all night long, until eventually they’re left for dead on the shoals. Then, an hour or two before sunrise, the pirates withdraw to the village for a visit to their favorite tavern, which apparently keeps the same hours as From Dusk Till Dawn’s Titty Twister. Their carousing is not nearly as relaxing as it’s supposed to be, however, for the captain keeps seeing the reproachful ghosts of the two girls from the wreck hanging around the saloon. Even a pirate captain is expected to keep his behavior within certain limits at a bar, and his ever more belligerent freaking out eventually gets the whole crew thrown out just before last call.

This is where things first turn properly Rollinesque— which is to say that it becomes difficult to be certain what’s really meant to be happening. Either the girls actually survived their ordeal, and the captain was just having a most uncharacteristic attack of conscience at the tavern, or they are now resurrected by unknown means and for unknown purpose. Whichever it is, they are seen roaming around the pirates’ island the next day, displaying no sign of physical injuries, but behaving as if entranced or in deep shock. Of course the captain and his crew can’t allow that, so they spend the following evening trying to catch them. They chase the girls first to the wrecking beach, where the pileup of shattered hulls turns the contest into a tense cat-and-mouse game, then across the shoals in the direction of another intermittent island. The pursuit lasts the whole night through, but even then does not end in success for the buccaneers. As dawn breaks and the tide comes in, the girls reach the relative safety of that second isle, where the treacherous combination of shoals and current will prevent the pirates from following until the next low tide.

It happens that there’s a second force restraining the captain and his minions from venturing onto the other island. In local lore, the forested isle has an unsavory reputation for supernatural habitation, and only Tina has it in her to scoff at demons, ghosts, and witches. The most haunted spot on that haunted ground is a ruined Medieval church, which is where the fugitive girls go in search of shelter and a place to hide. There, they meet an enigmatic woman in jester’s motley (Mireille Dargent, from Paris Porno and The Iron Rose) and an even more enigmatic man who bears a rather comical resemblance to Jim Henson (Ben Zimet). These two have been standing guard over an imprisoned devil (assistant director Miletic Zivomir), who apparently knows all about what the girls have been going through lately. The devil feels the castaways’ desire for revenge, and he persuades his jailers to let him temporarily loose to facilitate it. By having sex with the devil, the girls will gain access to all his power for a day and a night. That should more than suffice to give the captain and his crew what-for.

The Demoniacs is a remarkably off-kilter film, even for Jean Rollin. The plot is put together sideways, the characterizations are upside down, and the moral (the movie fairly explicitly has one of those, believe it or not) is installed backwards relative to the net vector of the story. I said before that it’s difficult to be sure whether the girls from the wreck are living or undead when they reenter the narrative for real during the second act. On the one hand, we’ve already seen their ghosts, but on the other, those manifestations could be explained away as figments of the captain’s conscience-haunted imagination. None of the other pirates see the specters, and the whole crew might well have been too drunk to tell the difference between death and severe shock by the time they were through brutalizing their victims. Normally, that uncertainty would become either the central mystery of the film (if it were the product of deliberate ambiguity which subsequent action was meant to resolve) or the defect that causes the whole thing to unravel (if it were instead the result of a lazy, sloppy mistake on Rollin’s part). In The Demoniacs, though, it somehow doesn’t matter one way or the other. Live or revenant, the castaways remain just a couple of vulnerable kids until the devil in the old church fucks his infernal might into them. Meanwhile, the major set-pieces are distributed very strangely, throwing off the pace and frequently failing to have the expected structural effects on the narrative. The scene with the captain seeing the ghosts, for example, is a total fakeout, even if the girls really are dead at that point, because The Demoniacs turns out not to be concerned with that form of revenge from beyond the grave. That incident’s real purpose is to initiate the process whereby Tina emerges as the true leader of the pirates, because she, unlike the captain, harbors no superstitious fear of the girls.

That leads me to my second point about The Demoniacs’ peculiarity, that the only characters who play anything like the roles we would expect of them are Paul and Le Bosco, who remain loyal but unreliable henchmen throughout. Actually, even that might be just a tad subversive, because the pirates theoretically embody archetypes imported from the swashbuckler genre, in which the number-two villain (Le Bosco for our purposes) often seeks to usurp his leader’s position. The captain’s fear of the castaways is odd to say the least, especially if we take the ghost scene to reflect only his own subjective experience. This is a man who has killed hundreds over the course of his criminal career; what on Earth could make these two victims so special? Are we simply to assume that all his prior murders were of mature men, capable at least in theory of fighting back? Then there’s Tina. Although she doesn’t participate directly, she’s the real instigator of the opening brutality on the beach, because seeing the castaways raped to death (or to what she assumes is death, anyway) gets her hot. (Apparently it got her even hotter in the original cut of the film, too. According to Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs, a shot of Tina masturbating to her colleagues’ rampage was edited out of The Demoniacs before its release.) Tina takes it nearly as a personal affront when the victims turn up alive the next day, and she grows almost suicidally reckless in her determination to finish the job. A character I haven’t mentioned yet, Louise the tavern madam (Louise Dhour, of Requiem for a Vampire and Dracula and Son), looks like the comic relief at first, but eventually emerges as a Cassandra-like prophetess of doom. The captive devil is the movie’s most compassionate figure, and the only one with both the power and the will to see justice done (although as we’ll see shortly, Rollin seems to take issue with the demon’s ideas of what justice means). The devil’s keepers are not monks, nuns, or priests as you would expect, but rather representatives of some ill-defined neo-pagan cult. And weirdest of all, the two girls at the center of this story are otherwise not the movie’s protagonists in any normal sense. At no point until the second act are they treated as viewpoint characters, and then only long enough to set up and perform their Satanic menage-a-troi. Furthermore, because they’re both mute (whether congenitally so or as an effect of their ordeal), there remains a mysterious aspect to their behavior. They can’t tell us what they’re thinking, and Rollin plays their cards very close to the vest at all times.

It’s in the final act, though, that Rollin’s decision to show us the castaways’ story through their enemies’ eyes becomes truly audacious, for reasons related to that moral I mentioned. It should be obvious by now that despite the supernatural trappings, The Demoniacs can be usefully thought of as belonging to the same genre as I Spit on Your Grave, Ms. .45, and Last House on the Beach. And this movie’s heroines, in their way, go further in pursuit of revenge than their counterparts in any other such film that I know of; I mean, say what you want about Thana’s descent into predatory vigilantism, but she never fucked a devil to acquire the powers of Hell! The vengeance these girls dish out must really be something to see, right? Nope. In fact, when the time comes, they dish out no vengeance at all. Oh, there’s some Carrie-like psychokinetic furniture-tossing that pretty thoroughly trashes Louise’s tavern, but at the moment of truth, they apparently can’t bring themselves to unleash their borrowed hellfire, however deserving the prospective targets. This sudden squeamishness has realistically tragic results for them, but neither does it help the pirates much in the long run. The idea seems to be that the girls realize at the last that revenge is a cheap and shoddy form of justice, and that the demonic power coursing through their systems can never really be used for good— justified evil is the best it can manage. So instead of exacting their eye for an eye, they permit the 24-hour deadline to lapse, and adopt a sort of quasi-Tolstoyan non-resistance, trusting in evil to be its own destroyer. I can’t overstate how breathtakingly weird it is. Who the hell ever heard of a rape revenge movie about the renunciation of revenge?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact