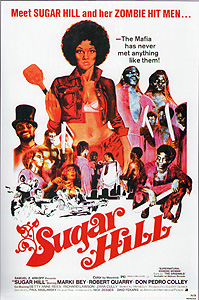

Sugar Hill/The Zombies of Sugar Hill/Voodoo Girl (1974) -***

Sugar Hill/The Zombies of Sugar Hill/Voodoo Girl (1974) -***

Voodoo had served American International well in 1973, when writers Maurice Jules, Raymond Koenig, and Joan Torres used it to revive a popular but decisively slain villain in Scream, Blacula, Scream, but clearly much more could be done with the Western Hemisphere’s most dreaded and misunderstood religious tradition than simply bringing vampires back to life. Especially if the studio meant to go on making blaxploitation horror movies, the bastard offspring of Roman Catholicism and the ancestral faiths of Africa represented a rich vein of fright-flick premises just waiting around for somebody to mine it. Voodoo had blood-rites, curses, spirit possession, menacing sorcery, a pantheon of weird and unfamiliar gods— and of course it had the zombie, which had just recently taken theater screens by storm in a form detached from its West Indian roots. Also, because Voodoo was most strongly associated with Haiti, the first majority-black country to throw off the bonds of European colonialism, it should have seemed a more natural fit than anything for a horror film aimed at a black audience. Sugar Hill, alas, comes nowhere near to realizing the potential inherent in a melding of blaxploitation and Voodoo-based horror, but even its worst failures are entertaining, and it offers enough glimpses of what it could have been to retain substantial interest above and beyond its kitsch appeal.

Somewhere on the outskirts of New Orleans, there is a popular night spot called Club Haiti. A white gangster by the name of Morgan (Robert Quarry, from Madhouse and Dr. Phibes Rises Again) would very much like to buy the place, but Langston the proprietor (Larry D. Johnson) isn’t interested in selling. Morgan leans on Langston with everything from better offers to veiled threats to open intimidation, but all without success. Finally, he sends Fabulous (The Black Gestapo’s Charles Robinson)— his top enforcer and, shall we say, his liaison to the local black community— around with a bunch of goons to let Langston know that the mob is through fucking around. When Langston still won’t agree to sell Club Haiti, Fabulous and his boys corner him in the back lot after hours, and beat him to death. Although Morgan’s girlfriend, Celeste (Betty Anne Rees, of Deathmaster and The Unholy Rollers), plausibly asks how he intends to buy the club from a dead man, the crime lord figures he can worry about that later.

In point of fact, Langston did have a will, and said testament confers ownership of Club Haiti upon his fiancee, Diana “Sugar” Hill (Marki Bey, from Gabriella and The Roommates). That seems doubly appropriate because Sugar is of Haitian extraction, although she broke with the culture and traditions of her forebears when she was very young. Langston’s death, however, has put her in mind to renew the old ties. Nevermind that Sugar’s ex-boyfriend, Valentine (Richard Lawson, from Scream, Blacula, Scream and Black Fist), is now a detective lieutenant with the Calais Parish police department, and has been assigned to cover the case; the justice Sugar wants is surer and more final than anything the law can offer. She goes out into the swamps, to the ruined plantation house where Mama Maitresse (Zara Cully) is said to live, in the hope of securing an audience with the reclusive centenarian. Mama Maitresse was the neighborhood Voodoo priestess when Sugar was a child, and while Sugar was never a believer even back then, the power of wishful thinking should not be underestimated. The old witch leads Sugar deeper still into the bayou, to a forgotten slave cemetery where she invokes Baron Samedi, the Loa of Death. The offering of Sugar’s engagement ring tickles the avaricious god’s fancy, and Baron Samedi (Don Pedro Colley, of Black Caesar and THX 1138) deigns to appear in person. Amused by Sugar’s lust for vengeance and her total fearlessness in the face of him, the Loa agrees to be of assistance. He calls the long-dead slaves from their graves and pledges them to Sugar as her private army; “Use them for evil,” he exhorts, “It’s all they know.”

One of Morgan’s thugs, Tank Wilson (Rick Hagood), mostly works at the dockside, running a crooked and exploitive cargo-shipping business between New Orleans and various ports in Latin America. Sugar and her zombie minions catch up with Tank while he’s rounding up a crew, and the reanimated slaves hack him to pieces with their cane-chopping machetes in his own warehouse. Valentine ends up working this case, too, and he is greatly puzzled by what little evidence can be found at the scene. Somebody left a 19th-century slave shackle near part of the corpse, and the medical examiner finds traces of mold and extremely dead skin on Wilson’s body wherever he was touched by his assailants— it’s like the perpetrators were literally rotting on Tank while they held him down and cut him up. Then a day or two later, another of Morgan’s men gets fed to some pigs, and a third turns up with a knife in his heart. It’s enough to make Valentine wonder if Sugar’s earlier statement that she’d like to see every one of Langston’s killers die slowly and painfully was more than just an idly vengeful musing. Valentine also finds some of the evidence— particularly the stuff seeming to suggest that the victims were killed by dead men— vaguely familiar from the days when he used to spend most of his time chasing after swindlers peddling fraudulent Voodoo medicine. He goes to see an old friend of his from back then, Professor Parkhurst of the Voodoo Library and Research Center (J. Randal Bell), to see if the clues really do add up to what he’s starting to think they do.

Meanwhile, Morgan is still trying to get his hands on Club Haiti, entering into negotiations with Sugar even as he orders Fabulous to step up his efforts to find and eliminate whomever it is that’s been preying on his men. Not for one second does it occur to Morgan that Sugar Hill is the enemy he has Fabulous hunting, nor does he suspect that her willingness to bargain with him is merely a delaying tactic with which to keep him busy while she works her way through his remaining subordinates. Once she finishes with them, Sugar is going to come for Morgan himself, and if Valentine and Parkhurst should get too close to the truth before she’s done, then she’ll just have to toss a little bit of Baron Samedi’s power their way, too.

The neat thing about Sugar Hill is that despite its frequent ridiculousness, it digs a bit deeper into Voodoo lore than the typical exploitation horror picture, and manages to sneak a wee bit of authenticity into the usual Hollywood confection of generic black magic. We do get the expected snakes, Voodoo dolls, and zombies, of course— in fact, we get some of the scariest non-flesh-eating zombies to be seen anywhere— but we also get Baron Samedi, and a portrayal of him that isn’t too far from accurate, at that. For one thing, the costume and makeup people have him looking exactly right, with his shabby tuxedo jacket, enormous top hat, and ashy, corpse-like complexion. This movie captures the Loa’s character pretty well, too, especially his paradoxical combination of immense power, petty venality, and curious devotion to earthly pleasures. Mama Maitresse describes him as the mightiest of the Voodoo gods, and yet he can be called to the material plane by an offering of jewelry, and he is willing to place himself at the service of a mortal in return for what turns out to be the promise of another woman to add to his harem. (By way of comparison, the “real” Baron Samedi is all-knowing and controls all passage between the worlds of the living and the dead, but is also a sexually voracious libertine with a pronounced weakness for tobacco and spiced rum.) And where this version of Baron Samedi diverges from authentic Voodoo tradition, he does so in the direction of the various African trickster gods, which is at least a defensible departure. (The Loa as a group evolved from assorted African deities, although Baron Samedi himself has no widely recognized antecedent in the Old World.) Unfortunately, the budgetary limitations of Sugar Hill are such that the more godlike Baron Samedi attempts to appear, the sillier he becomes. He’s fine when he’s impersonating taxi drivers or groundskeepers, shucking and jiving and generally putting one over on Whitey, but things go more badly awry the more of his true nature he displays. The low camera angles meant to suggest gigantic stature never succeed in making him look any taller than Don Pedro Colley’s already impressive 6’4”, the fog effects implying a rent between the dimensions would be more appropriate to an early Alice Cooper concert, and the electronic echo on Colley’s voice recalls nothing so much as Zandor Vorkov in Dracula vs. Frankenstein.

Luckily, we’re on firmer footing with the zombies. As with Giannetto de Rossi’s work on Zombie five years later, the makeup here is so cheap and simple that it probably shouldn’t work, but does anyway. The most effective elements of the zombie character design are the bulging, silver eyes and the thin film of cobwebs that shrouds their upper bodies. The total impression is roughly halfway between the undead in Plague of the Zombies and I Walked with a Zombie’s statuesquely menacing Carrefoure, and the scene in which the living dead crawl forth from their waterlogged graves might be the creepiest thing American International came up with in the whole 1970’s. Sugar Hill also subtly underlines an important but easily overlooked distinction between the standard movie zombie and its folkloric counterpart— Sugar’s undead followers are not mindless so much as they are will-less. They can understand instructions, stage an ambush, and use tools effectively, but they can do nothing whatsoever on their own initiative. Sugar commands and they obey, but left to their own devices, the zombies are little more than inanimate objects.

What most lets Sugar Hill down is the acting. Robert Quarry is good enough that I didn’t recognize him until the closing credits, and Don Pedro Colley does as much as could be asked with the Baron Samedi he was given, but everyone else seems to have been under the impression that they had signed up to compete in an ass-sucking contest. Marki Bey has a couple of okay moments, but even her overacting is stiff. Betty Anne Rees has nothing to do but be insulted by Morgan and get into a catfight with Sugar, and she can’t even do that convincingly. Charles Robinson demonstrates throughout that it is indeed possible to be the poor man’s Tony King. Most surprisingly, Richard Lawson looks for all the world as if he’s reading his lines off of cue cards, despite having a fairly decent track record both before and after Sugar Hill. Normally, he can be counted upon to deliver a solidly workmanlike performance, but in this movie, he’s pure high school drama club. It’s shameful. And while it’s frequently so shameful that it becomes a lot of fun to watch, it’s also rather frustrating in light of what might have been.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact