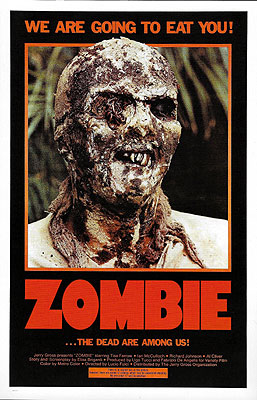

Zombie / Zombie 2 / Zombie Flesh-Eaters / Island of the Flesh-Eaters / Island of the Living Dead / Zombi 2 / Gli Ultimi Zombi (1979) ****

Zombie / Zombie 2 / Zombie Flesh-Eaters / Island of the Flesh-Eaters / Island of the Living Dead / Zombi 2 / Gli Ultimi Zombi (1979) ****

I remember when I first started renting a lot of horror movies on video tape. Weíre talking 1987 or thereabouts, when I was in the latter half of seventh grade. One of the first things I noticed was the astonishing number of zombie movies that were out there, and one of the first things I noticed after having watched a few of them was how many of them were of Italian origin. The movie to which I now direct your attention was my own first exposure to the Italian zombie gut-muncher, and while it wasnít quite the first of its breed, it is easily the most important. Zombie/Zombie 2/Zombie Flesh-Eaters/etc. not only kick-started a genre but also put director Lucio Fulci back in the spotlight for the first time since his previous star-turn as a director of gialli flamed out, putting a decisive and well deserved end to several years of unacknowledged toil in the subterranean basement of the Italian movie industry.

The origin of Zombie is a fascinating tale in and of itself. You might think it odd, for instance, that this movieís array of alternate titles includes a couple suggesting that itís the sequel to some other movie. Indeed, it almost seems that we are being asked to believe that Zombie is its own sequel! This, of course, is absurd, but the truth is not much less fantastic: Zombie was made as a sequel to Dawn of the Dead. How can this be possible-- how can it be that Lucio Fulci shot a sequel to George Romeroís movie for an Italian production company? Welcome to the wonderful world of international licensing agreements. In Italy, Dawn of the Dead was presented not as a sequel to Night of the Living Dead, but as a free-standing movie all its own. Flora Film, its Italian distributor, treated it much the same way that American companies usually treated Japanese monster movies. It was given a new score, a new title-- Zombi-- and even a new director; Dario Argento, one of the biggest names in Italian horror cinema, was hired to re-edit the film in order to bring it more into line with the perceived tastes of an Italian audience. Argento must have done a good job, because Zombi was a huge hit, and Floraís bosses instantly began itching for a follow-up. The trouble was that Romero had no such plans for the immediate future, and indeed seven whole years would go by before the release of Day of the Dead. But the studio heads at Flora didnít want to wait, and so, secure in the knowledge that they held all rights to the movie in Italy, they took it upon themselves to make their own sequel to Dawn of the Dead! (In fact, by 1990, there would be several such sequels, and nearly every zombie movie made with money originating between Sicily and the Alps would end up being called Zombie [pick a number] at some point in its lifetime.) That was all well and good inside Italyís borders, but when the studio responsible for this act of barely-legal subterfuge started shopping the movie around for foreign release, the companies that owned the distro rights to Dawn of the Dead in Spain or England or Germany-- to say nothing of the United States-- were sure to raise a fuss. How this played out in the rest of Europe I wouldnít even care to guess, but a resolution proved easy enough in the English-speaking world. Fortunately, there was not yet an American flick called Zombie, so Zombi 2ís American distributor could just remove the numeral and still have the name recognition necessary to take advantage of whatever buzz the movie had generated abroad. The English, meanwhile, decided that wasnít lurid enough, so the movie goes by Zombie Flesh-Eaters in the U.K.

Given its rather shady origins, the quality of this film is nothing short of staggering. The story is, like that of its model, simple but effective. After an enigmatic but attention-getting prologue in which a backlit man fires a pistol into the head of a bound and shrouded figure as it slowly rises from its bed, the movie jumps to a sailboat negotiating the waters around Manhattan Island. This boat appears to be abandoned, but when two men from the harbor patrol board to investigate, one of them is killed by a stinking fat man who tears out the policemanís throat with his teeth before the dead copís partner empties his revolver into him, blasting him clear overboard. The boat is registered to a doctor named Bowles (in the American version, anyway-- other versions call him Bolt), whose daughter Ann (Tisa Farrow of The Grim Reaper/Anthropophagous the Beast) claims not to have heard from him in several months. The last she knew, he was on the island of Matul, in the Antilles.

The curious story attracts the notice of a newspaper reporter named Peter West (Ian McCulloch, who would appear later the same year in Dr. Butcher, M.D./Zombie Holocaust), and he and Ann meet when they both have the same idea at the same time, and sneak aboard the boat under cover of darkness within mere minutes of each other. The only clue they turn up is a letter from Dr. Bowles to his daughter, in which he tells her that he is dying of some mysterious illness, and that he knows he will never leave the island alive. The letter also makes veiled reference to Bowlesís business on Matul, something about helping a colleague of his study the very disease to which he apparently succumbed. Armed with this tantalizing information, West contacts his boss at the newspaper, who secures airline tickets to the Antilles for him and Ann on a hunch that a really big scoop is lurking behind the strange turn of events.

The plane to the Antilles naturally does not land on Matul, and so West and Ann are forced to look for passage by boat. After a short search, they come across a pair of American vacationers, by the names of Brian Hull (or Bryan Curt, depending on which version you see-- either way, heís played by Al Cliver from Black Velvet and Forever Emmanuelle) and Susan Barrett (Auretta Gay). The couple had been meaning to spend their vacation cruising the waters of the archipelago anyway, so they donít require a whole lot of convincing before they agree to give Peter and Ann a lift. All concerned will have cause to regret this later. The first indication of trouble (that is, if you disregard the whole missing father/dread disease/man-eating fat guy angle) is the fact that Matul does not appear on any chart of the Antilles. If you ever find yourself in an Italian horror movie, stay the hell away from uncharted tropical islands! The next hint comes when Susan has Brian stop the boat so that she can go scuba diving for a bit. (You can tell sheís in for it because she strips down to just a g-string before donning her diving gear.) Itís bad enough when she finds herself face-to-face with a tiger shark, but when a hideously scarred man with no scuba gear joins the fray, things get even worse. Not only is there no sign of how this guy could have gotten so far out to sea without an air tank or even a snorkel, but when the shark bites his arm off at the elbow, he doesnít really seem to mind, and his blood is brown! More alarming still, the guy then goes and takes a great big bite out of the shark! You bet your ass Susan gets back on the boat, and she does it fast, too.

What the four travelers find when they finally reach Matul has got to be the most unsanitary hospital Iíve ever seen. (And Iíve seen it at least twice. The same set was used again for Dr. Obreroís lab in Dr. Butcher, M.D.) Seriously, thereís no suspension of disbelief necessary at all to accept that dead people could start rising up to eat the flesh of the living in a place like this. And as it is gradually revealed, that is indeed the nature of Matulís problem. Dr. Menard (Richard Johnson, best known to horror fans from his role in The Haunting, but who would eventually be reduced to appearing in movies like this and The Great Alligator) has been studying the problem, hoping to find a cure for what he understandably assumes is some sort of exotic disease. Annís father had come to Matul to assist him. Menardís wife Paola (Olga Karlatos, who, and Iím completely serious, would show up in Purple Rain five years later) wishes he would give up and go home. She seems to think the natives of Matul are on to something in their belief that the islandís zombie problem has nothing to do with disease and everything to do with voodoo. But nobody listens to her, and she ends up on the receiving end of the most famous eyeball-gouging in the history of Italian horror cinema when a pack of zombies infiltrates the Menard villa while everyone but Paola is off at the so-called hospital. This, of course, means that the zombies have now spread to literally every part of Matul, and that body count time has officially begun. Eventually, it will all come down to whatís left of the cast holed up in the rickety old hospital while hundreds of zombies close in from all sides. And in true Romero style, those few who survive the night have a rude awakening in store for them the next day...

For all the flack that Lucio Fulci has taken over the years (and Iíll be the first to admit that a lot of it is justified), the man deserves to be taken seriously as a director if for no other reason than that he made Zombie. Sure, the movie is in some ways just a rip-off of Romeroís earlier work, and there can be absolutely no question but that thatís how its creators saw it, but this film does not at all merit the sort of out-of-hand dismissals it has so often received from those outside the hard core of gore-movie fans. Those who call Zombie derivative fail to notice how greatly it differs from Romeroís movies in terms of style and tone. To begin with, the relocation of the action from western Pennsylvania to a remote island in the Caribbean has a far-reaching effect on the way the movie works. Romeroís zombie movies concern themselves with the unspeakable intruding itself into the settings of everyday life. Zombie has its characters unwittingly go out to meet the unspeakable on its own territory. In Night of the Living Dead, the question is whether the characters can hold out until such time as they can be rescued by the representatives of a still-fully-functioning authority. Dawn of the Dead concerns itself with the efforts of a few well trained and heavily armed people to carve out and defend a small island of order in the face of the chaos represented by the rapidly increasing ranks of the living dead. Zombie, on the other hand, places its characters in a situation of which chaos is already the undisputed master, and challenges them to live long enough to reach safety somewhere outside its reach. Romero wouldnít try this approach until 1985, with Day of the Dead. This is not to say that this difference of approach makes Zombie in any way superior to Night of the Living Dead or Dawn of the Dead; indeed, I reckon it rather weaker than both. But the difference is a significant one, and its presence means that, regardless of its creatorsí intentions, Zombie is more than a mere carbon copy of the Romero living dead cycle. Nor can it be said that Zombie suffers from the pervasive illogic that bedevils so many European, and especially Italian, horror films. Its characters behave plausibly throughout, there are none of the jarring lapses of continuity or baffling expositional gaps that are the usual hallmark of such movies, and the only things that are left unexplained are left that way for good and compelling reasons, and the movie is better for it. Later Fulci films would display more imagination and a bold penchant for the surreal that is absent here, but he also often failed to bring his more personalized visions to convincing life on the screen, and prosaic though it may be, Zombie is surely his most satisfying and compelling work.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact