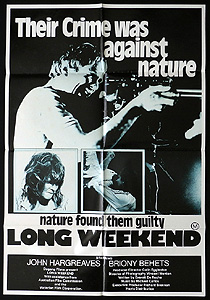

Long Weekend (1977/1979) *****

Long Weekend (1977/1979) *****

If there’s a better venue for a “Mother Nature’s Revenge” movie than the Australian countryside, I can’t imagine what it could be. It doesn’t even have to be the Outback; anywhere you go Down Under, if there’s wildlife around, you’d be only slightly paranoid in assuming that it probably wants to kill you. The coastlines have great white sharks, saltwater crocodiles, stonefish, sea snakes, cone shells, and worst of all, box jellies. The interior has tiger snakes, brown snakes, taipans, death adders, and funnel-web spiders. Even kangaroos and cassowaries can be dangerous to an unwary city-dweller. So basically, baby-eating dingoes are the least of your wildlife-related worries. It’s no surprise, then, that there are indeed Australian animal-attack movies on the standard model, or something close to it. Dark Age and Rogue concern killer salties. Razorback is about a gigantic, freak-of-nature boar. And from most one-liner descriptions (to say nothing of the original theatrical trailer), you would naturally assume that Long Weekend was basically the Aussie Day of the Animals. Long Weekend is actually a great deal more complex and ambiguous than a single sentence can easily encapsulate, however, and comparing it to William Girdler’s magnificent travesty acknowledges only one of several possible interpretations, while selling it miles short as an example of cinematic art.

When we’re introduced to Marcia (Briony Behets, from Night of Fear and Stage Fright) and her husband, Peter (John Hargreaves, of Deathcheaters), it’s immediately obvious that their marriage is in trouble, but the true cause of their domestic strife is shrouded in mystery. We can see at once that the invariably disastrous combination of oblivious, egocentric man and passive-aggressive woman is a factor, yet there also seems to be something else more concrete in play. When Peter and Marcia argue, for example, about what radio station to listen to in the car, or how best to arrange the appropriate standard of care for his dog, Cricket, while the two of them go out of town for a three-day weekend, it always seems like they’re arguing around some other issue too big and too dangerous to be faced directly. In any case, Peter and Marcia are well aware that their relationship is in urgent need of repair, and the aforementioned vacation is supposed to be their Krazy Glue of Love. Unfortunately, the plan for this getaway seems less likely to end the couple’s two-person civil war than to open yet another front in it, and the method whereby they devised said plan reveals a lot about how they got to this point in the first place. Rather than collaborate with his wife on an itinerary that both of them would enjoy, Peter has unilaterally settled on a camping trip to Lunda Beach, an edge-of-nowhere spot auspiciously situated next door to a slaughterhouse, where Marcica is guaranteed to be bored out of her skull all weekend long. And instead of putting her foot down and refusing to go along with a scheme that she justifiably hates, Marcia just picks one petty quarrel after another over her husband’s management of the details. It’s a microcosm of their whole marriage, really. He never thinks about anybody but himself, and she would rather have something to bitch about than be satisfied. It’ll be a fucking miracle if these two make it through three whole days in the wilderness without stabbing each other in the face.

Mind you, the battling spouses may have an even bigger problem on this holiday. Marcia isn’t really paying attention to the TV news while she waits for Peter to come home from carbine-shopping, but if you are, you’ll hear an odd story about people in Sydney’s western suburbs being inexplicably attacked by flocks of normally docile white cockatoos. That report will seem increasingly relevant as the weekend wears on, and the campers face steadily escalating difficulties with the local fauna. There’s a weirdly persistent ant infestation at their campsite, and mold gets into their food with baffling speed whenever Marcia takes it out of the freezer hooked up to their ute’s battery. An extremely aggressive eagle starts hanging out in the trees above their tent, and although some of its behavior can probably be explained by Marcia’s stealing what Peter assumes to be its egg, the bird seems abnormally purposeful in avenging the theft. A possum brazenly scavenges food from the camp one night, and bites Peter hard enough to draw blood when he attempts to capture it. Eventually, the vacationers even experience a mass bird attack like the one described on the news. Meanwhile, as the incidents proliferate, one can’t help noticing how wantonly destructive Peter and Marcia are. I’ve already mentioned the eagle’s egg, which Marcia not only steals, but eventually smashes against a tree. That isn’t the half of it, though. Both campers litter like crazy, and Peter thinks nothing of tossing glowing cigarette butts into patches of visibly inflammable underbrush. He also runs over a kangaroo on the overnight drive to the beach, and he’s so indiscriminate about shooting off his carbine and spear gun that one hesitates to dignify his activities with the term “hunting.” Also, upon awakening for the first time at the campsite, Peter takes an axe to one of the nearby trees, apparently out of sheer boredom. Note that he doesn’t actually cut it down; he just hacks the shit out of it, and leaves it standing in exactly the optimum spot to crush tent or vehicle whenever it inevitably gets around to dying and falling over. If I were Mother Nature, I’d be pretty pissed off at this pair of hooligans, too!

Eventually, though, Peter and Marcia’s growing fears crystallize around three phenomena whose menace is all the more disturbing for being so much less direct than a dive-bombing eagle or a microbial offensive against their food supply: the dark shape in the water, the unearthly howl, and the other campsite farther down the beach. Peter likes to surf, so he naturally spends a lot of his time at Lunda Beach out in the water. Every time he dives in, there’s something out there with him, some big creature that lurks just far enough away to be hidden from him by the turbidity of the breakers. Marcia can see it from the top of the dunes, however, and much as she’s grown to dislike her husband, the thought of that thing getting to him terrifies her. After two close calls, Peter shoots and kills the mysterious animal— which turns out to be a perfectly harmless dugong when its carcass washes up on the beach later. You’d think that would be the end of the issue, but somehow that dead dugong just won’t stay buried. And somehow it seems to be closer to the campsite every time it comes loose from the sand.

The howl begins troubling the campers from practically the moment they first enter the woods separating Lunda Beach from the highway. At first, it’s scary simply because nobody likes to think about being in close proximity to an animal that they can’t identify. As the weekend wears on, though, Marcia begins ascribing it a more sinister significance. The more she hears it, the more the howl sounds to her like the crying of a baby— which happens to be one of her crazy switches just now, on account of that unspoken business she and Peter keep almost fighting about. It’s a long, sordid story, but the short version is that a few months ago, Marcia almost died on the operating table while having an abortion that neither she nor Peter wanted her to have, terminating a pregnancy that neither she nor Peter wanted her to have, either. They’ve been unable to forgive either themselves or each other ever since. Marcia never comes right out and admits that the howl makes her feel like she’s being literally haunted by her dead fetus, but that’s pretty obviously what’s happening here, and her sanity is visibly fraying as a consequence.

Those other campers also take on a darker aspect with the passage of time. When Peter first spots their van parked on the beach in between the tide lines, he and Marcia think of them mainly as an annoyance in waiting. The couple came out here to fix their marriage in peace and quiet, not to make new friends or whatever. The audience, meanwhile, can’t help but wonder if maybe this isn’t where a bit of Deliverance will work its way into the story, and the next scene or two following Peter’s discovery are clearly designed to encourage such speculation. Things look altogether different, however, come Sunday afternoon, when an excursion down the beach reveals that something has gone catastrophically wrong for Peter and Marcia’s largely unseen vacation neighbors. The van is still standing right where it was before, but now the tide had come in, submerging it up to the roofline in the surf. The associated campsite, meanwhile, is deserted apart from a traumatized beagle, but Peter can find no bodies anywhere. Well, none except for the girl who evidently locked herself in the van, and stayed there until the rising tide drowned her.

The mysterious but surely horrid fate of the other campers is as close as Long Weekend ever comes to confirming that something truly out of the ordinary is going on at Lunda Beach. Otherwise, it’s entirely possible to write off Peter and Marcia’s travails as a combination of bad luck, stress reactions, and sheer dumbassery. However much Peter has invested in an image of himself as Jungle Jim Down Under, it’s obvious from the outset that he’s only slightly less of a suburban tenderfoot than his wife. So when he gets jumped by that possum, for example, it might be the natural world punishing him for his human arrogance, but it could also simply be that he’s a fool who messed with a wild animal after smoking a bunch of weed. Marcia’s losing battle with the ants and the mold freaks her out thoroughly enough, but a campsite is much harder to keep sterile than a kitchen. Maybe no more exotic explanation than that is necessary. And by the time the really creepy manifestations begin— like the jack-in-the-box dugong— Peter and Marcia alike are so obviously cracking up that we should think twice about taking anything they experience at face value.

In any case, that cracking up is the main event here, and the couple’s mutually destructive incipient madness is a far greater threat than even the most extravagant interpretation of Nature’s vengeance that the events of this story will support. The true horror of what ultimately happens to Peter and Marcia is that it’s both bleakly inevitable and so, so obviously avoidable. Time and again, opportunities arise for the campers to escape their fate, and time and again, Peter’s pig-headed selfishness and Marcia’s petty vindictiveness combine to draw them another step closer to the grave instead. Fish gotta swim and birds gotta fly, right? And of course for that very reason, neither Marcia nor Peter is exactly wrong in blaming the other ever more stridently as their situation deteriorates— they each merely fail to notice their own contributions to disaster.

Curiously, though, despite their incompetence, their shitty attitudes, and their frequently vile behavior, both of the protagonists remain somehow sympathetic, even (hell, especially) after they go straight-up bonkers, and surrender to their most primal, irrational fears. It may be because early on, the filmmakers remember to offer us at least a few glimpses of them not acting like assholes, and making a good-faith effort at marital damage control despite the glaring misguidedness of their approach to the task. In any case, though, Peter and Marcia seem much more real and nuanced than their counterparts in most horror movies, the sort of characters you take pity on instead of wishing them ill. Furthermore, director Colin Eggleston, writer Everett De Roche, and even cinematographer Vincent Monton on some subliminal level are careful to prevent the couple from ever looking like idiots rather than fools. It’s a subtle distinction, but an important one. A reasonably intelligent viewer without much wilderness experience should easily be able to imagine him- or herself making many of the same basic mistakes in Peter and Marcia’s position. So with each new fuck-up comes a sinking feeling in the pit of your stomach: “Oh, Jesus… Don’t do that. Please don’t do that…” instead of “Oh, come on! What the fuck is wrong with you?!” Toss in some extraordinarily committed performances by John Hargreaves and Briony Behets, made all the more impressive because the two actors have nobody to play off of but each other for virtually the entire film, and you’ve got a movie that I can recommend without hesitation to any but the most impatient and easily bored horror fan.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact