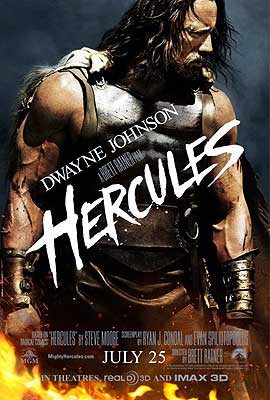

Hercules (2014) **Ĺ

Hercules (2014) **Ĺ

I hate to be bamboozled; so does everyone, I expect. I also expect that everybody learns early onó like about the first time they see what the toy at the bottom of the cereal box really looks likeó that advertising is to a great extent the art and science of bamboozlement. So we should all know by now not to trust what we see in TV commercials, even when it looks like thereís little opportunity in them for marketing sleight of hand. And yet sometimes you just want what theyíre selling so much that you let your guard down, and fail to notice that what theyíre selling isnít what youíre buying until itís already too late. Right before Juniper and I went to see Hercules, we were talking about how much fun it was going to be to see a movie about a legendary hero that didnít shy away from the legend in favor of pretending to tell the ďtrueĒ story. I mean, look at that trailer. Thatís the Hydra! Cerberus! The Nemean Lion! The Erymanthian Boar! Four of the actual twelve laborsó and four of the most fantastical, at tható crammed into one 30-second TV spot! And then the movie started, and a montage of exactly the footage from the ads unspoiled while a voiceover grumbled, ďYou think you know Hercules? You know the legend. Let me tell you the true story of HerculesÖĒ Thatís right. Weíd been bamboozled. But over the next hour and a half, a funny thing happened. While Hercules remained committed as ever to permitting only the tiniest trace amounts of fantasy to intrude upon itself, it did enough right on other fronts to win back a fair amount of my goodwill. It wasnít the movie I wanted, nor was it the movie Paramount and the reanimated corpse of MGM promised, but it was a fair enough update of the more grounded style of peplum, which is something we havenít seen much of lately, either. And since itís more a Gladiators 7 for the 21st century than a proper Hercules movie, I donít have to feel awkward about reviewing this Hercules before the Steve Reeves and Lou Ferrigno versions.

Right, so weíve already established that this Hercules (Dwayne ďthe RockĒ Johnson, from Doom and The Scorpion King) isnít really the son of Zeus, but he does have one thing in common with his mythological counterpart beyond his sweet lionskin hoodie. His life of itinerant adventure is dictated at least partly by the ghastly deaths of his wife and children. Hercules was blackout drunk at the time, so he doesnít know what actually happened, but when he came out from under all the wine, his loved ones were all ripped to shreds. It was generally assumed that he committed the murders himself, so King Eurystheus (Joseph Fiennes) ordered him banished from Athens. Ever since then, Hercules has wandered the Mediterranean basin, earning his keep here and there with his titanic strength and fearsome skill at arms. Along the way, he has drawn to himself a small but formidable company of fellow mercenaries: his nephew, Iolaus (Reece Ritchie, from 10,000 BC and Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time), who isnít much good in a fight, but is a master of the mythological ballyhoo that keeps the teamís asking price nice and high; his oldest friend, Autolycus (Rufus Sewel, of She-Creature and Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter), who got him into the soldier-of-fortune business in the first place; Amphiarus of Argos (Ian McShane, from Death Race and Too Scared to Scream), who claims the power to foretell the future; Atalanta the Sythian (Ingrid BolsÝ Berdal, of Cold Prey and Chernobyl Diaries), archer and charioteer; and Tydeus (Aksel Hennie), a mad foundling who is as much Herculesís attack dog as he is his friend and colleague.

One evening, while the gang are unwinding in a tavern after chasing off a nest of pirates, Hercules is accosted by a Thracian princess called Ergania (Rebecca Ferguson). Her father, Lord Cotys (John Hurt, of Immortals and Snowpiercer), rules the most powerful city-state in the region, but his domains have lately come under attack from the warlord Rhesus (Tobias Santelmann). Rhesus commands great armies, but that is said to be the least of his strengths. Centaurs serve as his cavalry, if you believe the rumors, and some even credit Rhesus with the power to bewitch whole cities, so that the men he conquers fight for him as loyally as if he were their own kin. All in all, a challenge truly fit for the son of Zeus, donít you think? If Hercules will lead the army of Cotys against Rhesus and defeat him, he and his companions will be paid twice his considerable weight in gold. Theyíd be set for life with that kind of money, and Hercules could at last realize his cherished dream of retiring to a farm in one of the Black Sea colonies, where heíd never have to don his armor or heft his war club again. Ergania has a deal.

Mind you, Lord Cotysís strategos, Sitacles (Peter Mullan, from Session 9 and Children of Men), isnít thrilled about playing second fiddle to a mercenary, but itís not like heís been able so much as to slow Rhesus down, so who gives a shit what he thinks? A quick review of the troops pinpoints the most serious problemó the Thracians are skirmishers unschooled in the formation-fighting techniques that make the armies of the great southwestern city-states so effective. The first thing Hercules and his companions will have to do, then, is to teach them how to form a phalanx with a firm shield wall. That takes time, but it doesnít look like Rhesus means to allow his enemies any. Cotysís agents report that the warlordís forces are marching even now on the lands of a primitive tribe called the Bessi. Little more than savages, the Bessi are under Cotysís protection, so an attack on them is effectively an attack on Cotys as well. At the lordís insistence, Hercules leads mercenaries and unprepared regulars alike into what turns out to be a clever trap. Perhaps thereís something after all to the rumors of Rhesus wielding mind-control powers, for far from greeting Cotys and Hercules as defenders, the Bessi ambush the Thracian forces at a village rigged to look like the site of a massacre. The Thracians fight their way out of the killing box (even a poorly maintained phalanx is more than a match for a bunch of guys with sickles, clad mainly in tattoos), but itís a much closer call than Hercules likesó or than Cotys can afford.

The poor performance of his soldiers against the Bessi persuades Cotys to sit down, shut up, and let Hercules do his job, no matter what provocations Rhesus might offer. Itís a smart move, for when the Thracians and the barbarian horsemen meet in battle at last, the contest goes all Cotysís way. Rhesus himself is among the captives led back to the Thracian capital in chains, and the whole city rises in celebration. The defeated warlord says an odd thing to Hercules before heís hauled down to the dungeon, though. Rhesus tells Hercules that heís backing the wrong sideó that Cotys is a cruel tyrant against whom all the less civilized people of Thrace are ready to rise in rebellion if only they could be organized. Thereís no reason for Rhesus to make such a claim unless he sincerely believed it, because he comes from a culture that valorizes conquest as something manly and heroic. If the warlord sought merely to steal Cotysís throne, he should be boasting of how close he came to success, not pleading extenuating circumstances.

Then Ergania comes to Hercules in secret (or so she hopes, anyway), begging him to smuggle her son, Arius (Blackwoodís Isaac Andrews), out of Thrace when he and his followers depart in the morning. Evidently the reason why Lord Cotys doesnít call himself King Cotys instead is because the latter title rightfully belongs to Arius. Cotys murdered the boyís fatheró which his to say, his own son-in-lawó in order to gain control of the city-state. Arius was safe until now, because his need for a regent gave Cotys legitimacy despite his regicide. But now that Hercules has furnished the usurper with an army strong enough to subdue even the most restive barbarians on the frontiers of Thrace, the old man can derive legitimacy from success at arms instead, and Arius starts looking like a danger to his grandfatherís position. Yeah, slick move there, son of Zeus. Mercenary or not, Hercules has enough sense of justice to be horrified at how heís been tricked into fucking things up. Autolycus and the others donít have to join him (after all, no oneís going to be paying for this job), but Hercules himself will be sticking around in Thrace for however long it takes to set things right again. Iolaus, Amphiarus, Atalanta, and Tydeus each owe enough to their leader to back him without hesitation, even in the absence of an attendant payday. Autolycus, however, will take some time to come around. As for Cotys, heís got a pretty strong hand to play. For one thing, Ergania and Arius live with him in his palace, well within convenient seizing distance. For another, heís the one with the army, and Hercules has seen to it that itís a deadly army indeed. Letís also not forget Sitacles, who has plenty of reason to keep a sharp eye on Hercules, and to report any irregularities in his behavioró like, say, a sotto voce conversation in the corridor with Erganiaó to the regent. And finally, the wily old bastard had the foresight to anticipate that his relations with the mercenaries might not stay friendly. Turning on Cotys is going to buy Hercules a reunion with an old enemy from back home.

Hercules began working its way back into my good graces very subtly. The tavern scene that introduces Ergania feels strange for a peplum movie, but it would be perfectly in keeping with an 80ís barbarian film. Indeed, itís very much like the bit in Conan the Barbarian that precedes the heroesí arrest by King Osricís soldiers. Almost subliminally, that scene reset my expectations in a pulp adventure direction, giving me a frame of reference to replace the mythological one that had lured me into the theater in the first place. And within that pulp adventure frame of reference, Hercules is fairly successful. Most of the characters have attributes instead of personalities, but thatís to be expected in this genre. There was a time when one could also have said the same of the mercenariesí tight teamwork, mutual loyalty, and general readiness (Autolycus excepted, obviously) to go to the mat for whatís right, but these days, it actually counts as a refreshing change of pace to see a movie thatís so comfortable with the basic concept of heroism. Similarly surprising, even though it shouldnít be, is Herculesís approach to the major action set-pieces. Although the fight scenes are frenetic enough to suit the most exacting modern taste, theyíre carefully orchestrated with an eye toward audience comprehensionó even to the extent of including long-range overhead shots of the biggest, most complicated battles. And those who left 300 griping about the absence of authentic Classical Greek warcraft despite an entire subplot hinging on one characterís physical unsuitability for phalanx fighting will find a tonic in Hercules. Not only do we get to see the ancient Greek phalanx correctly formed and deployed, but the combat scenes in this movie even show how and why the formation so dominated the battlefield in Classical Antiquity. The practiced eye will also note a mostly accurate depiction of how other troop types (massed archers, charioteers, light cavalry, etc.) were employed in and around ancient Greece. Thereís even a nod to the hypothesis that the centaur legend grew out of early contact between Greek colonists on the north shore of the Black Sea (for whom the main military application of horses was to haul chariots) and the peoples of the Eurasian steppe (who were among the most accomplished horse-riders the world has ever known). If youíre going to disappoint me by telling the ďtrueĒ story behind a myth that someone should finally make a no-fucking-around movie about, then you can at least make it up to me by getting this much stuff recognizably right.

At the same time, Hercules offers itself as an antidote to another annoying tendency in recent action-adventure cinema, in that it isnít relentlessly gloomy. To some extent, I mean that literally; I canít remember the last time I saw a first-run movie so blessedly free of That Damned Blue Filter and its kindred affronts to the eye, Ash-o-Vision, Rust-o-Vision, and Bile-o-Vision. But Iím also talking about the tone of the film, which rarely indulges in brooding, moping, or scowling. Thatís pretty astonishing, considering that there isnít one person among the core cast who lacks a tragic past of one sort or another. Thereís a snarky sense of humor at work here that reminds me a lot of ďHercules: The Legendary Journeys.Ē Like that show, the movie is able and willing to laugh at itself without descending to the level of spoof or self-parody. Indeed, self-deprecating humor is explicitly built into the premise, because the mercenaries are shown to have a carnival barkerís attitude toward their carefully cultivated reputations. Itís arguably anachronistic, but so much effort has been put into establishing the Greek milieu in other ways that Iím willing to roll with it. Dwayne Johnsonís spirited, charismatic performance has a lot to do with making Hercules work in not-quite-comedy mode. He has terrific timing, and like a lot of pro wrestlers who have gone on to conventional acting, he seems instinctively to know just how seriously to take himself. Meanwhile, I suspect his wrestling background also provided him with some valuable insight into other, more serious aspects of the character. After all, Hercules too puts on an exaggerated persona and relies heavily on showmanship and shit-talking to overawe his opponents, but still has to fall back on his strength, agility, toughness, and stamina at the end of the day. The stakes for his performances are higher, thatís all.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact