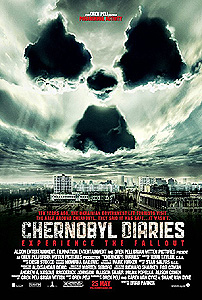

Chernobyl Diaries (2012) ***

Chernobyl Diaries (2012) ***

Occasionally I’ll see a movie that makes me marvel over how it’s possible that nobody ever thought of it before. Well, perhaps I should qualify that a little. Obviously the direct-to-video realm is so vast at this point, and its constituent films so little exposed to media scrutiny, that there’s almost certainly no way of knowing anymore whether an idea has really never been tried. But the fact remains that some premises cry out to be used for years if not decades before anyone takes them up on the offer. Take, for example, a survival-horror movie set in the dead zone around Chernobyl. The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone almost has to be the creepiest place on Earth— the site of one of history’s most infamous nuclear disasters and at least three major ghost towns, the largest of which once held a population of nearly 50,000. The evacuation, when it was finally ordered the day after the explosion of Reactor #4, was conducted on terms which guaranteed that Pripyat, the biggest and most seriously contaminated settlement within the fallout area, would remain filled with the refugees’ personal belongings, looking eerily lived-in even after indomitable nature had begun to reclaim what man rightly fears to use. The Exclusion Zone encompasses some of the most radioactive places on Earth, including some where a human will start to sicken literally within minutes, even with the best protective clothing and equipment. Striking mutations of plant and animal life have been reported within the Zone, together with several new species of fungus that apparently use melanin to convert gamma radiation into chemical energy the way photosynthetic plants use chlorophyll to harness sunlight. The Exclusion Zone even harbors mineral substances found nowhere else on this planet, most notably a crystalline zirconium silicate dubbed “chernobylite,” with a uranium content as high as 10%. It’s a place where reality has been rendered so fantastic that nearly any form of dark fantasy could take flight from it. There’s room in the Exclusion Zone for everything from atom-age hauntings to mutant bears that would make the one from Prophecy look like Teddy Ruxpin, and yet somehow Chernobyl Diaries is the first film I can remember to do anything with this diabolically fertile plot of nightmare real estate.

Mind you, the specific premise of Chernobyl Diaries is one that could not have been used until relatively recently, since only in the mid-1990’s did the Ukrainian government begin permitting any non-official access to the most heavily affected parts of the Exclusion Zone. Before then, a Chernobyl-based horror film would have had little choice but to feature scientist or soldier protagonists, and although a very interesting movie could have built around such characters, the makers of this one were aiming closer to The Hills Have Eyes than to The Hills Have Eyes 2. The central figures in Chernobyl Diaries are a young American expatriate named Paul (Friday the 13th’s Jonathan Sadowski); his little brother, Chris (Jesse McCartney); and two girls who have accompanied Chris on a European vacation which is set to climax in Moscow after the travelers link up with Paul at his home in Kiev. One of the girls is Chris’s paramour, Natalie (Olivia Taylor Dudley, of Chillerama), who will soon be upgrading to fiancee status if Chris gets his way. The other is Amanda (Devin Kelley), a friend of Natalie’s whom Paul is under fraternal orders not to hook up with under any circumstances (although it’s clear enough that Paul means to spend the Russian leg of the others’ trip angling for chances to disobey those orders). The relationship between the brothers is familiar from horror movies dating back at least to Dracula, Prince of Darkness: Paul is the Teflon-coated risk-taker, while Chris is the pathologically responsible tight-ass who invariably winds up paying the consequences whenever one of Paul’s schemes goes awry. Their sojourn in the former Soviet Union will be the ultimate example of the pattern, in both senses of the word.

To his credit, Chris attempts to put his foot down the very second Paul comes to him and the girls at breakfast one morning to ask, “Have you ever heard of ‘extreme tourism’?” What Paul means is that he recently met an ex-special forces operative named Yuri (Dimitri Diatchenko, who provided the voice of seemingly every Russian character in an English-speaking video game for the last ten years or so), who now makes his living conducting tours of the ghost city of Pripyat. There is some indication that what Yuri does is not quite strictly legal— that perhaps he exploits both his old military connections and his country’s post-Communist inuredness to corruption to gain him and his tour groups access to places they shouldn’t technically be allowed to see— but he’s been at it for five years with no trouble thus far. I can’t fault Chris for feeling a little betrayed when Amanda and Natalie both go along with Paul’s plan to engage Yuri’s services, but the fact is I’d jump at the chance for a day trip to Pripyat, too. When the foursome arrive at Yuri’s office, they meet another couple who will be coming along with them: the Australian Michael (Nathan Phillips, from Wolf Creek and Snakes on a Plane) and his Norwegian girlfriend, Zoe (Ingrid Bolsø Berdal, of Cold Prey and Going Postal). Chris can’t seem to make up his mind whether to be reassured that someone other than his thrill-crazy brother trusts Yuri enough to take part in the venture, or irritated at having to spend the day with a pair of strangers.

The first sign of serious trouble comes right at the checkpoint marking the edge of the Exclusion Zone. The guards manning the gate won’t let Yuri and his passengers through, no matter what blandishments or bribes the former soldier offers them. They say military maneuvers are underway in the Zone, but Yuri knows enough to recognize that line as almost certain bullshit. Bullshit or not, though, the guards stick to their story, and refuse to open the roadblock. Paul and Michael in particular don’t take this setback graciously, and Yuri is in any case reluctant to part with the tourists’ money. Since he happens to know other, less closely watched routes to Pripyat, he proposes to sneak his customers into the ghost town via one of them. Again Chris objects (and this time he has Natalie backing him up), but again he is voted down. Sneaking into Pripyat it shall be.

Just as Yuri anticipated, there is no sign of any army maneuvers in Pripyat— just a lot of spooky, deserted, Soviet-era apartment blocks painted with patriotic murals in naïve Socialist Realist style, and a park still tricked out for a May Day celebration that will never take place. Amanda, photographer that she is, is in heaven. There’s one major scare, when the tourists surprise a brown bear rummaging in one of the apartment buildings, but even that, in retrospect, seems more exhilarating than threatening. After all, the poor bear was plainly every bit as freaked out as they were. Yuri, however, keeps noticing things just slightly out of place— things suggesting that he and his customers really aren’t the only people in Pripyat this afternoon, despite the apparent lack of drilling soldiers. He keeps whatever suspicions he’s forming to himself, but becomes very forceful about the need to clear out of the dead city well before sundown. And really, why mention the animal carcasses in places they shouldn’t be or the piles of warm ashes indicative of recent campfires when he has the more abstract menace of radiation to hustle the others along? The Exclusion Zone may be safe enough for short visits, but more than a few hours in it at a time is asking for trouble.

You can imagine, then, the reactions all around when everyone climbs back into Yuri’s van, and the fucking thing won’t start. The gas tank is full and the battery has plenty of charge, but when Yuri lifts off the engine’s access cowling, he finds that every single lead from the distributor cap is melted. That’s not something he can fix on the spot, so unless he can raise the checkpoint guards on his handset radio, he and his tour group will just have to camp out overnight in the van. Calling the checkpoint avails them nothing, which is probably only to be expected, what with all the electromagnetic interference oozing out of the melted-down reactor up the road. Camping out is not a popular course of action, but the memory of that bear in the apartment quickly makes hiking the twelve miles back to the guard post even less so. In fact, however, peckish bears are the least of anyone’s worries out in the Exclusion Zone tonight. The feral dogs, to begin with, are much more actively predatory than a bruin, even if they’re less impressive on a one-for-one basis, and the glow of the interior dome light (which Paul and the others insist on keeping lit) has made those dogs very curious about the van. But the real trouble has more to do with those extinguished campfires and whatnot that Yuri has scrupulously avoided mentioning. Distributor cap leads don’t spontaneously melt in a turned-off automobile, and neither bears nor dogs nor soldiers on training exercises are in the habit of sabotaging engines.

I was somewhat worried, going into Chernobyl Diaries, that it was going to be another “found footage,” faux-verite horror film. There was the title, for one thing, but also the advertising ballyhoo attributing Chernobyl Diaries to “the makers of Paranormal Activity.” (In fact, it was co-scripted by— get this— Paranormal Activity writer/producer Oren Peli and Asylum hacks Carey and Shane Van Dyke, the latter of whom wrote the Asylum’s Paranormal Activity cash-in film, Paranormal Entity!) There was enough interest and value inherent in “The Exclusion Zone Has Eyes” as a premise that any extra gimmickry would just get in the way, so it pleases me to report that Chernobyl Diaries limits its footage-finding to the opening montage, which is quickly revealed to be Chris watching videos of the vacation thus far on his iPad. It also pleases me to report that although Chernobyl Diaries might as well be the movie for which the word “unassuming” was coined, it nevertheless does a respectable job of realizing its very modest ambitions. Undeniably, this sort of “young people make bad decisions and pay with their lives” story has been done very nearly to death (and we had The Cabin in the Woods to remind us of that just a month or so ago in case we were inclined to forget it), but Peli, the Van Dykes, and director Bradley Parker do at least run through the routine competently enough. The kids in the tour group act like dumb-asses with a consistency I don’t think I’ve seen since the short-lived slasher revival of the late 90’s, which makes them difficult to stomach at times. However, their dumb-assery takes forms that seem believable coming from unprepared people in the grip of total panic, and this cast is much better at their jobs than most of those I recall from the likes of Urban Legend or (looking back a bit further) Friday the 13th, Part VII: The New Blood. The evocative setting is used very well indeed, and considerable thought clearly went into the perils that an abandoned pocket of radioactive wilderness, in a foreign country with a recent history of brutal and corrupt government, would present even before factoring in a tribe of brain-damaged mutant cannibals newly escaped from a secret military hospital.

I’m a little ambivalent on the handling of the mutants themselves, though, and the mixture of respect and frustration they provoke from me is almost a microcosm of my reaction to the movie as a whole. At no point are the mutants ever characters in the full sense, like their counterparts in either version of The Hills Have Eyes. That makes for a lot of unutilized potential, especially since squatting in less polluted parts of the Exclusion Zone than Pripyat (like the cities of Chernobyl and Poliske) is a significant real-world phenomenon. It also nudges Chernobyl Diaries in the direction of the zombie movie, which seems like the least compelling thing that could possibly be done with an Exclusion Zone horror film in 2012. At the same time, though, treating the mutants strictly as a depersonalized, hostile Other serves to keep the focus tightly on the protagonists and their situation, creating an effect of gritty immediacy similar to that of the “found footage” technique, but without incurring the disadvantages associated with it. In fact, the best scene in the movie reminds me a lot (in a good way) of the climactic top-floor sequence in [REC]. I still think I would have liked to see more of the enemy, but I can understand and respect what the filmmakers were trying to do by keeping them on the periphery.

Generalizing that mixed assessment to Chernobyl Diaries overall will require some major spoilers, so consider yourself warned. Simply put, this movie actually plays too fair with its scenario. The deck is stacked very heavily against the tour group from the moment Yuri’s van refuses to start, and the odds grow longer still when the guide is killed and Chris seriously injured shortly thereafter. By the time it becomes obvious that the vacationers are going to have to spend a second night in Pripyat, it is equally obvious that there is simply no way for any of them to survive, barring some egregious cheating on the writers’ part. That Peli and the Van Dykes resist any temptation to cheat is most commendable, but their creative scruples sharply limit the amount of suspense that the second and third acts can generate. Inescapable doom, to be truly effective, must sneak up on characters and audience alike. Paul, Chris, Natalie, Amanda, Michael, and Zoe are all too obvious from the outset as people who would stand no chance in the face of real danger, so when Yuri is the first to die, there’s no question but that it’s as good as over already. Now contrast, say, John Carpenter’s The Thing or Dan O’Bannon’s The Return of the Living Dead, in which the inevitability of disaster is apparent only in retrospect. Looking back from the ends of those films, you can see how everyone in them was actually fucked from the word go, but in any given scene along the way, it seems superficially as though the protagonists have a fighting chance. In Chernobyl Diaries, the only reason I ever anticipated a casualty rate below 100% was because I mistakenly didn’t trust the filmmakers to have the courage of their convictions.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact