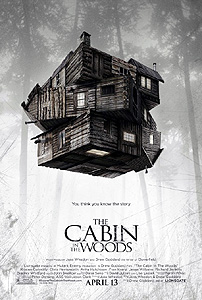

The Cabin in the Woods (2009/2012) ****½

The Cabin in the Woods (2009/2012) ****½

You might think that the author most responsible for “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” would basically be able to write his own ticket for the rest of his career— especially since he had a hand in launching the Toy Story franchise as well! I mean, if Joe Eszterhas could shrug off Showgirls for years because the industry still remembered him as the Basic Instinct guy, then surely creating a TV show so widely and intensely adored that a different network brought it back for two more seasons after its initial cancellation ought to earn Joss Whedon forgiveness for the Buffy the Vampire Slayer movie and Alien Resurrection! Instead, though, the aughts were for Whedon a rough patch of “Holy crap! Which deity did you piss off?!” proportions. Executive meddling during the final season of “Angel;” “Ripper” and a “Buffy” spin-off cartoon turned down by everybody in the business; “Dollhouse” picked up only in half-season increments and dumped prematurely; “Firefly” killed off after half a season and aired out of order, with the last three episodes never broadcast at all; Wonder Woman cast into Development Hell. The pre-release misadventures of The Cabin in the Woods stand out even in that company, however. Shot in the spring of 2009, The Cabin in the Woods was originally slated for release the following February. Then some dope got it into his head that all the cool kids were putting out their horror, sci-fi, and fantasy movies in 3-D, and ordered it shelved temporarily so that the possibilities of post-production conversion could be explored. That exploration (and arguments attendant thereupon with Whedon and director/co-writer Drew Goddard) dragged on for months, so that the next “official” release date announced was in January of 2011. Then the fucking studio went out of business. We’re not talking about some pissant indie production house, either— this was MGM, once the biggest, richest, and most powerful movie studio in the world! MGM had been looking for many years like the Habsburg Empire of the film business, though, and by that analogy, November 10th, 2010, was the company’s 1918. The firm’s bankruptcy made orphans of at least two completed pictures (and a hearty Nelson Muntz “Hah-hah” to those of you who were drooling with anticipation over the prospect of a new Red Dawn), but fortunately for Whedon and Goddard (and for us too, as we’ll soon see), Lionsgate happened to be in the market for horror movies right about then. They’d just released Saw 3-D: The Final Chapter, and no businessman likes to see the demise of a perennial cash cow like that series had become. The Cabin in the Woods, for reasons I’m not going to say a single word about, offered no franchise potential even for the people foolhardy enough to make American Psycho 2, but it did offer something else of value to a post-Saw Lionsgate: a metric shitload of street cred with horror fans, and with it a continued hand in the pocketbooks of an avid and loyal niche market. The price was right, too, and so The Cabin in the Woods’ travails have at least come to a happier ending than those of most Whedon projects. Maybe between it and The Avengers, Whedon can build up enough studio goodwill to spare his next undertaking the usual hassle.

So how does one acquire street cred with horror fans? It’s simple enough, but “simple” is not the same thing as “easy.” You have to shake us up. You have to jar us out of our complacent and arrogant assumption that we’ve basically seen it all— but (and this is the hard part) you have to do it in such a way that our expectations are still met. As Carol Clover astutely observed, there is a ritual aspect to horror fandom, and creators working within the genre neglect that ritualism at their peril. Much as we might complain about them, we like our Final Girls and our silver bullets and our zombie-killing head shots. We like radiation, we like crosses and garlic, and we like it when the mad scientist is destroyed by his own creation. Conversely, we really don’t want our serial killers to use guns; we’re still not totally sold on the whole “running zombies” thing; and we absolutely fucking hate it when vampires’ skin sparkles in direct sunlight. And of course we do have a tendency to watch any old shit at all in the hope of encountering that one particle of interest— one shiver down the spine, one image we can’t un-see, one dreadful fate we’d never before thought to be thankful not to suffer except vicariously. It’s easy to grasp, then, why so many writers, artists, and filmmakers in the horror field don’t bother trying to go beyond the ritual. If fans want the familiar in any case, it’s ever so much easier just to give it to them, and to forget about pushing the limits past that. The greatness of The Cabin in the Woods lies not merely in that it does go beyond the ritual, but that it is indeed overtly about going beyond the ritual, on levels both textual and subtextual. It takes one of the most familiar setups of the past 40 years and blows it wide open, becoming in the process a horror movie about horror movies— about making them, about watching them, and most of all about demanding more from them.

Surely it is no coincidence that the setup in question was also that from which The Evil Dead proceeded, itself a once-revolutionary film that attained its classic status by doing more than fans expected with a commonplace premise. The cousin of a college upperclassman named Curt (Chris Hemsworth, from the relaunched Star Trek) has recently acquired a long-disused cabin in a remote stretch of mountains, and Curt and his girlfriend, Jules (Anne Hutchinson), think that sounds like a terrific place to spend spring break. Also along for the trip will be their stoner friend, Marty (Fran Kranz, of The Village and Rise: Blood Hunter); Jules’s newly single roommate, Dana (Kristin Connolly); and a recent acquaintance of Curt’s by the name of Holden (Jesse Williams), with whom Jules hopes to set Dana up. Dana, for her part, has other ideas about that, but her resolve softens just a bit when she actually meets the guy. Obviously we’ve seen this sort of thing not just in The Evil Dead, but countless times before: young people who can be roughly sorted into a set of crude character stereotypes head out to the middle of nowhere, oblivious to the horrible fate that will soon befall them despite a panoply of portents they’d have to be imbeciles to miss. We can even be reasonably sure what’s going to happen to whom. Jules and Curt will be ambushed in the middle of an amorous embrace, probably at the very beginning of the second act. Marty will wander off on his own while stoned out of his gourd, and that’ll be the last we see of him— unless maybe he meets his end instead while playing a practical joke on someone who he doesn’t realize is the villain. Holden will die heroically just before the climax, sacrificing himself in defense of Dana. And Dana, at the last, will face down the threat alone, perhaps triumphing only to be killed off in the sequel’s pre-credits sequence. The only thing that still seems completely up in the air at this point is what specifically is going to slaughter these kids. Cannibal family? Satanic cult? Vengeful ghost? Retarded hermit serial killer? Militant vegetarian goblins? A jovial devil played by Victor Buono? Does it even matter, really?

Ah, but something isn’t normal here. Our “virginal” Final Girl candidate is newly single because she was just let go from a hugely unethical affair with her economics professor. Our nitwit jock alpha-male is a straight-A sociology major on a full academic scholarship, who downplays his intelligence and sensitivity merely in jest. Our brainiac, conversely, is an even more adept athlete than our jock. Our slutty dumb blonde is pre-med. Even the pothead is a misfit genius with the problem-solving mind of an engineer and the searching curiosity of a philosopher. Oh— and the inevitable unseen personages surreptitiously watching the protagonists’ every move? Well, we do see them, and Mordechai the ersatz Crazy Ralph (Tim De Zarn, of Tales from the Crypt Presents: Demon Knight and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning) notwithstanding, they’re all way the hell off-model for this story as we’ve been encouraged to understand it. For one thing, the watchers aren’t in the woods at all, but rather in a high-tech underground installation beneath the cabin, and they effect their peeping via spy satellites, audio bugs, closed-circuit fiber-optic television cameras, and heaven knows what else. “Buffy” fans will find this outfit distinctly reminiscent of the Initiative, the secret government program to contain and combat the supernatural that figured in that show’s fourth season. Whatever this lot are up to, we get to know them mainly through the interaction of four technicians. Sitterson (Richard Jenkins, of Let Me In and The Broken) and Hadley (RoboCop 3’s Bradley Whitford) are old hands in what appears to be the organization’s main control room. Truman (Brian White, from In the Name of the King: A Dungeon Siege Tale) is the new guy in central control, whose presence provides an excuse for more exposition than would otherwise be plausible; had The Cabin in the Woods been made 50 years earlier, he would surely be portrayed as an annoying boob from Brooklyn. Lin (Amy Acker, of Fire and Ice: The Dragon Chronicles and “Angel”) works in the chemistry department; there seems to be some bad blood between her unit and the aforementioned men’s. As those folks and a few others of lesser significance squabble, posture, and horse around like any bunch of coworkers in a stressful, high-stakes field, a picture gradually emerges of just what their field is, and just how high those stakes are.

You remember what I said about rituals? Well, what’s going on at the cabin is exactly that, and Sitterson and his colleagues are, for lack of a better term, the priesthood charged with conducting it. Specifically, it’s a ritual of sacrifice designed to prevent the rising of the Ancient Ones, and evidently it’s been going on at regular intervals for quite some time. (“Remember when you could just throw a girl into a volcano?” Hadley muses at one point, reflecting on all the rigmarole that the modern version entails.) Not only that, but other sacrifices broadly akin to this one are in process all over the world— in Tokyo, Stockholm, Buenos Aires, who know where else? The details are unique to each culture, and have clearly shifted over time, but the modern North American version calls for five archetypal youths— the Virgin, the Scholar, the Athlete, the Fool, and the Whore— to be lured out to a cabin built in the late 19th century by a family of insane backwoods penance fanatics called the Buckners. Once there, they are tempted into the cellar, which is packed to the rafters with strange artifacts, each one a summoning device for some terrible creature or creatures. The Ancient Ones, you see, require that their sacrifices be volunteers in a sense. The victims must choose of their own free will (albeit obviously not by informed consent) the means of their destruction, and it must be their own actions that determine whether they live or die. The “priests” may stack the deck against the offerings as heavily as they wish, but there must always be a way, however far-fetched, for the latter to prevail. Thus all the redundancy— the Ancient Ones demand a sacrifice on the appointed date, but they don’t require a one-for-one success ratio. There’s only one problem with this mechanism for securing the continued survival of the species (I mean apart from how human sacrifice is just generally a dick move). The youth of today, for whatever reason, are a lot better at outwitting, outfighting, and out-whatever-ing monsters than their counterparts in previous generations. The North American sacrifice program, for example, has had to rely ever more heavily on psychoactive drugs (which is to say that chem department Lin works for) to make the chosen victims stupider, hornier, and more arrogant in order to maintain its high success rate, and poorer nations without access to such technologies are now finding it very difficult to do their parts in keeping the Ancient Ones mollified. Things are going especially badly this year, with only Japan and North America still in play as the kids at the cabin inadvertently call the Buckner family forth from their graves— and as I’ve already observed, Jules and her friends are an exceptionally sharp bunch.

What I find myself thinking of most now that I have to start analyzing The Cabin in the Woods (instead of just bouncing up and down in fanboyish glee over it) is an earlier attempt to deconstruct some of the horror genre’s more outmoded tropes, Wes Craven and Kevin Williamson’s Scream. As 1996 recedes deeper into the past, carrying away with it that initial rush of euphoria at seeing, for the first time in what felt like ages, a slasher movie that didn’t really aggressively suck, consensus among thoughtful fans seems to have shifted toward the position that Scream didn’t truly accomplish its stated mission. That is, although it took the crucial first step of articulating the unspoken rules of the post-Halloween horror movie in terms that even non-fans could immediately grasp, it had no follow-through whatsoever. Largely abandoning the criticism of the genre that was supposedly its reason for being, it retreated during the final act into a lazy rehearsal of the very clichés that it had just spent an hour or so exposing. The Cabin in the Woods doesn’t have that problem, or at least not to anything like the same extent. Although it does function for roughly two thirds of its length as a composite copy of The Evil Dead, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and the later Friday the 13th sequels, Whedon and Goddard never lose sight of their aim to examine and to comment upon (sometimes literally, via the dialogue in the control room scenes) nearly every one of the tropes they employ, from the mad harbinger of doom whom no one ever heeds to the incorrigible knife-dropping habit of Final Girls. And crucially, The Cabin in the Woods becomes less formulaic as its story progresses, and the events in and around the cabin wane in direct importance. The only commonplaces which Whedon and Goddard can be meaningfully accused of falling back on in earnest are those of their own writing, and complaining about that is a bit like Saul Zaentz suing John Fogerty for plagiarizing himself.

The Cabin in the Woods also avoids a rather subtler trap that Scream fell into. When the characters in that film talk about the clichés of horror movies, what they really mean for the most part is the clichés of slasher movies, but The Cabin in the Woods is serious about taking on the entire broader genre. After all, going to the Bad Place is so basic a starting point that there’s really only one alternative within the context of a horror story— either the protagonists go where the evil is, or the evil comes to them. And when the breadth of the sacrifice program’s monster menagerie is revealed, we see that almost literally anything could have come in answer to the kids’ unwitting summons, even if some threats are apparently invoked more often than others. (Nobody in the bunker who didn’t have money on “Zombie Redneck Torture Family” in the staff betting pool is happy to see the Buckners get picked yet again, and Hadley in particular laments that he’s never once seen the merman called into action in all his years on the project.) Furthermore, what glimpses we’re allowed of the other rituals underway pull in even those subgenres that are totally incompatible with the Spam-in-a-Cabin framework. In Tokyo, for example, they’re doing the post-Ring Stringy-Haired Ghost Girl thing, and I have no doubt that the avenues not taken over there would include giant, radiation-breathing dinosaurs and infestations of umbrella goblins. The Cabin in the Woods is thus practically without peer as a game of Spot the Reference, but mere nodding and winking at the audience is the least of this movie’s concerns. Rather, by finding a plausible way to tie together nearly every horror story told in the West for the last 40 years using only the often unnoticed similarities that already exist between outwardly unconnected premises, Whedon and Goddard invite us to ask ourselves how long we can really be content to hear, read, and watch minor variations on those premises over and over again. With Hollywood more devoted to remakes now than it’s been at any time since the early 1930’s, that’s a distinctly germane question— even if my own personal answer is almost certainly, “indefinitely, so long as the minor variations keep being sufficiently interesting.”

Looking over what I’ve written so far, I think maybe I’ve made The Cabin in the Woods sound more like a formal exercise than a proper movie. It is a formal exercise, really, but as any fan of Whedon’s TV shows knows, he has a long habit of using such experiments as a goad to his creativity, and his track record with format stunts is largely one of striking success (although the exhaustingly hyper-serialized fourth season of “Angel” and the detestable “Once More, with Feeling” are instructive exceptions to that rule). The 80’s-horror pastiche portion of this film owes a lot of its effectiveness as satire to the fact that it’s genuinely a good 80’s-horror pastiche. The ready wit and sharp dialogue characteristic of Whedon’s TV productions (in which Goddard often had a hand) is very much in evidence here as well, and the cast includes several of Whedonvision’s most capable familiar faces. (It includes Tom Lenk too, alas, but his role is at least a minor one.) Apart from the Buckners, there are no clear-cut villains in this story, and those protagonists who last long enough to learn what’s really going on are thereby put in a position guaranteed to revoke their status as clear-cut heroes no matter how they choose to deal with that knowledge. And most importantly, The Cabin in the Woods partakes of the quality that made “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” seem so revelatory in the late 1990’s, a seemingly effortless tonal agility. It repeatedly turns on a dime from action to bathos to that indefinable sensation of “Whoa…” that I associate most strongly with the best science fiction, all while maintaining its sense of humor, and it earns at the same time the right to treat the utterly ridiculous (like Marty beating the shit out of a hillbilly zombie serial killer with his gigantic, stainless-steel bong) seriously. The one mood it never really manages to hit is fear, ironically enough, but given the main paratextual theme of present-day horror cinema’s senile incompetence, I half-suspect that that might actually have been part of the point all along.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact