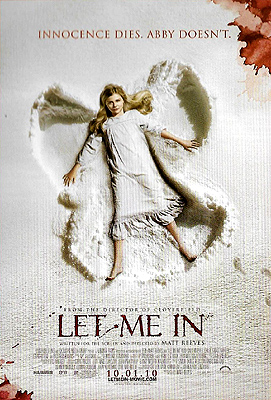

Let Me In (2010) ***½

Let Me In (2010) ***½

It’s fitting, I suppose, that Hammer Film Productions has been since the late 1970’s a sort of undead company. Officially, Hammer survived the financial debacle of To the Devil… a Daughter, but that movie’s failure marked the end of their sustained operation as a feature filmmaking firm. Three years passed before the Hammer logo was next seen on a movie in its first run, and that picture (a calamitously ill-received remake of The Lady Vanishes) was the last for three decades. Throughout that time, Hammer remained in theory a going concern, but in practice, it only rarely did much of anything. An hour-long anthology series called “Hammer House of Horror” ran for thirteen episodes on British and American television in 1980. A further thirteen “movie of the week”-format episodes aired under the collective title, “Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense” in 1984. “The World of Hammer” followed in 1990, but that sad series of horn-tooting reminiscences on the studio’s past glories was deemed so exciting that it was not picked up for broadcast (or VHS release in the United States) until 1994. And that was it until quite a few years into the 21st century. Hammer was traded around from one group of investors to another throughout the next decade or so, each revolution promising the revitalization of the once-prestigious company, but none of the buyers ever got as far as making an actual film. But now, at last, we can say it in all seriousness: Hammer has risen from the grave. The current owners have indeed made four movies, with a fifth in the works, and what’s more, they’ve managed to secure at least limited theatrical runs for three of them. Let Me In, made in partnership with the American Overture Films, spent the longest time on theater screens, and not surprisingly, either. Whereas Beyond the Rave, The Resident, and Wake Wood had only the largely notional nostalgia value of the Hammer name to help sell them, Let Me In was able to ride the buzz generated by Let the Right One In, the superb Swedish film of which it is a very close remake, which had justly breached the normally impregnable critical prejudice against horror movies two years before. As an ardent fan of the old Hammer, it pleases me to report that Let Me In is very nearly as good as its Scandinavian model, even if it doesn’t add much to the original template.

Let Me In opens on a really nifty flash-forward. It’s a winter night in 1983, and a squadron of police cruisers are convoying an ambulance through the desolate countryside around Los Alamos, New Mexico, toward Memorial Hospital. Inside the ambulance is a criminal suspect, deep in shock and suffering severe acid burns all over his face, arms, and upper torso. As we learn when the detective handling the case (Elias Koteas, from Lost Souls and The Haunting in Connecticut) arrives at the hospital to interview the patient, he apparently inflicted those burns on himself— and deliberately, at that! The detective believes the disfigured man to have some connection to a recent spate of murders in which the victims were completely drained of blood, and the first thing he asks when the nurse allows him in is whether the suspect belongs to some sort of Satanic cult. (The acid destroyed the man’s tongue and melted his lips together, but the policeman brought along a pen and notepad to facilitate any testimony his suspect might be in the mood to give.) Just then, a call comes in from the front desk, alerting the detective that the suspect’s daughter was just in the lobby, looking for her father. While the cop pumps the reception nurse for anything she can tell him about this turn of events, the machines monitoring the patient’s vital signs start going bugshit, drawing every staff member within earshot to see what’s the matter. What’s the matter is that the burned man has left his room— through his tenth-floor window and down to a squishy ending on the pavement below. The sole clue left behind is the message, “I’m sorry, Abby,” scrawled on a page of the policeman’s pad. Let Me In will now spend roughly half its length explaining how we got here.

That story begins not with cops, murders, chemically self-immolating men who may or may not be Satanists, or disappearing little girls, but rather with a twelve-year-old boy named Owen (The Road’s Kodi Smit-McPhee). Owen lives with his emotionally distant, gravely depressed, and not-altogether-with-it mother (Carla Buono, from Cthulhu and The Unquiet) in a scruffy Los Alamos apartment complex. His parents split up a couple months ago, and although it’s an open question whether Mom’s psychological problems and vehement religiosity are more a cause or a symptom of the marital meltdown, it’s clear enough that both are now major factors driving the forthcoming divorce. Owen is not coping well with this state of affairs, nor is he coping well with the panoply of social ills that small, weak, withdrawn, bookish children are prey to. He has literally no friends, but three implacable enemies in the band of bullies led by a sadistic kid called Kenny (Dylan Minnette), who can be counted upon to make life as difficult and humiliating for him as possible at every turn. Owen responds to these pressures by retreating into a combination of voyeurism and violent fantasy. On the one hand, he uses his low-power telescope and the commanding vantage point afforded by the placement of his bedroom on one of the building’s corners to spy on his neighbors— especially Virginia (Hellraiser: Inferno’s Sasha Barrese), the sexy young woman who lives across the courtyard on the ground floor, and her randy, middle-aged boyfriend, Jack (Chris Browning, of Terminator: Salvation and Beneath the Dark). And on the other, he likes to put on a mask and smuggle carving knives out of the kitchen to play at being one of the slasher characters so popular in contemporary horror movies. One night, his pervy surveillance catches the arrival of a 50-ish man (Richard Jenkins, from Wolf and The Core) and a pretty but alarmingly skinny girl about his own age (Chloe Moretz, of The Eye and The Amityville Horror), the latter of whom shockingly tromps through the fresh snow barefoot while hauling her meager luggage in from the taxi.

The girl is named Abby— yes, that’s right— and Owen meets her in the courtyard playground the following night. At first, he’s sort of guardedly excited at the prospect of a kid in the neighborhood who knows nothing about the seven years’ worth of personal history that cements his place as a loser, but Abby shuts down any expectations the boy might be forming by telling him bluntly that they can’t be friends; her voice when she says that holds a note of weariness that no child her age should be able to produce. Owen has no way of realizing this yet, of course, but Abby has very good reason for wanting to avoid social entanglements. She’s a vampire, perhaps centuries old, and the man who lives with her in the flat next to Owen’s is not her father, but her Renfield. Every few days, when Abby’s hunger for blood grows too strong to be denied, he goes out and murders somebody so that the girl will have something to eat. Small wonder the pair relocate often and travel light! If the photographs in Abby’s flat are any indication, she and her human familiar met up when he wasn’t too much older than Owen is now, and it would appear that the pressure of being a serial killer is finally starting to get to him. The murders he commits in Los Alamos are clumsy, slovenly affairs, and when Abby calls him out on his poor performance of late, he openly admits that he halfway wants to be caught. As you’ll no doubt have surmised on the basis of the opening scene, he will be soon enough.

As if they hadn’t been already, things get very perilous for everybody from there. Abby’s companion, sloppy as he’d become, was a necessary part of the system because he possessed something that she does not: an adult’s capacity for sober judgement and self-control. Abby may be older than any human alive, but her cerebral physiology is still that of the twelve-year-old girl she was when she became a vampire. No matter how much she learns, no matter how much experience she acquires, she will always have the thought process of an impulsive child, and the attention-getting murders she commits when she is forced to fend for herself clearly demonstrate this mental shortcoming. Abby starts preying on her own neighbors, and when she attacks Virginia, she does so in full view of Jack, who chases her away before she’s had a chance to sever Virginia’s spinal cord. When Virginia bursts into flames while trying to guzzle her own blood in her hospital bed the next morning (the windows in her room afford lovely eastern exposure), it gives that detective we met earlier a lot to think about. Meanwhile, Abby and Owen do indeed become first friends and then… well, whatever it makes sense to call a couple of pre-teens who are more than friends, which has the effect of drawing him ever deeper into the vampire’s bloodstained world even before he accidentally discovers what she really is. The conflict between Owen and Kenny’s gang escalates, too, when the put-upon boy takes to heart Abby’s advice that the only way to deal with bullies is by meeting the threat of violence with its actuality. Owen’s initial victory leads Kenny to enlist the aid of his older brother, Johnny (Bret DelBuono)— and let’s just say that Kenny had to learn his antisocial behavior from somebody. Eventually, Abby decides that the time has come to hit the road again, but that’s yet one more thing for which she’s been accustomed to relying on Renfield to get right.

It’s a crying shame that a movie this good should have so little reason for existing in the first place. Let Me In is an almost-brilliant film, but most of the ways in which it is almost brilliant are also ways in which Let the Right One In actually did achieve brilliance. Chloe Moretz and Kodi Smit-McPhee turn in breathtaking, heartbreaking performances, but then so did Lina Leandersson and Kåre Hedebrant. The relationship between Owen and Abby could teach a thing or two to the creators of every film, book, and TV show about human-vampire romance to emerge since the early 1990’s, but again so could the relationship between Oskar and Eli. When Let Me In began with the Renfield guy already on his way to the hospital, I got excited over the possibility that the remake would address the need to establish a personality distinct from Let the Right One In by structuring the story in a radically different way, but in the end, the Anglo-American version settles for minor tweaks here and there. Most of those tweaks involve tradeoffs, too, rather than solid improvements on the Swedish interpretation.

To begin with the most obvious adjustment, Let Me In has little time for or interest in grownups. Let the Right One In’s pub crowd has been pared back to just Jack and Virginia, and we see them almost solely through the children’s eyes. Owen’s parents are minor presences indeed, his mom never both fully in the shot and in focus at the same time, and his dad no more than a seldom-heard voice on the telephone. Even Abby’s companion has had his role reduced in comparison to Håkan in the Swedish version. This singleminded focus on the kids is appropriate in the sense that twelve-year-olds really do mostly inhabit worlds of their own, in which adults outside the family figure only when they are actively demanding attention, and the treatment of Owen’s parents further plays up the totality of his isolation from normal life. That last is an important consideration, given that we will eventually be asked to root for him running away from home to become a vampire’s pet serial killer. Concentrating on Owen and Abby at the expense of the adult characters also makes for a more streamlined narrative than we got from the occasionally rambling Let the Right One In (to say nothing of the compulsively rambling novel from which both movies ultimately derive). But at the same time, the paucity of adult perspectives in Let Me In inadvertently soft-pedals the moral weight of the choice Owen faces. He’s just a kid, and a troubled kid at that. He can’t begin to imagine the life that lies ahead of him as Abby’s consort— the decades of slaughtering his fellow men on her behalf, or even more so the decades of growing misery as he matures while she does not, rendering his love for her ever more untenable and unconscionable. Director Matt Reeves succeeds admirably at making us see Abby as Owen does, but that’s only half of the picture. We need to see her as she really is, too, and for that we need the perspectives of characters whose perception of Abby is not clouded by the emotional turmoil of first love. Let the Right One In did that by dwelling on the regulars at the pub, showing how their lives were disrupted first by the death of Jocke, and then by transformation of Virginia into a vampire. And by making Håkan a viewpoint character in his own right, the Swedish version also encouraged a deeper pondering of the Renfield lifestyle, even if Tomas Alfredson and John Ajvide Lindqvist stopped short of explicitly stating that Håkan was once in Oskar’s position.

That leads us to another subtle difference between Let Me In and Let the Right One In: the remake is a great deal less ambiguous than the original. This extends not merely to the writing and direction, but to the performances of the principle players as well. Håkan might have been a child when he and Eli met; Abby’s companion certainly was. Oskar’s parents divorced long enough ago to have reached a new equilibrium in their relationship, and neither one is clearly in the wrong for the inadequacy of Oskar’s home environment; Owen’s mom is a basket case, and the state of her relationship with his father is one of open warfare. Alfredson’s direction was introverted to the point of minimalism; Reeves is flashy— often ingeniously so— and he’s not at all ashamed to employ conventional Hollywood scare tactics when he thinks they’re called for. On those scores, I very much prefer Let the Right One In (although I wouldn’t trade Let Me In’s car crash shot from inside the back seat for anything), but the divergent effects of the two different acting styles is a far tougher call. A close comparison between Lina Leandersson and Chloe Moretz is the easiest way to see what I mean here. Nearly everything Leandersson does can be read in several ways. When Eli tells Oskar that they can’t be friends, she might be trying to protect herself, either from outside scrutiny or from the emotional torment of an impossible relationship. Or she might be speaking from her conscience, seeking to keep Oskar from getting involved in something that can only hurt him in the long run. Or it might just be that Eli hasn’t been human in so long that she can’t remember how to talk to another child any more than she can remember how it feels to be cold. Leandersson’s reading of the line is as distantly matter-of-fact as the staging, lighting, and cinematography, and it’s up to us to extract whatever nuances of meaning we can from it. When Moretz delivers the same line, though, we know exactly what Abby is feeling. We can hear how badly she wants what she’s saying not to be true, but we can also hear her resignation to the fact that it is. Abby has done this before, after all— probably many times— and she knows how any friendship that might develop between her and Owen is doomed to end. Neither approach is obviously superior to the other; Moretz’s technique grants more access to the character’s interior life, but Leandersson’s leaves more leeway for active engagement between the audience and the film. Either way, both actresses demonstrate a virtuosity far beyond their years. To one extent or another, the same dichotomy applies all across both casts, and from what I can see from reviews and comments elsewhere on the internet, people who strongly favor one of these movies over the other are largely reacting to this stylistic cleavage. Let the Right One In’s fans accuse the Anglo-American version of too much hand-holding, while Let Me In’s grumble about the non-acting of those affectless Swedes.

There are, however, two small points on which Let Me In holds a clear advantage over its predecessor. First, you may recall me praising Let the Right One In for minimizing the plot thread from the novel in which Eli is eventually revealed to have been a boy during his mortal life. Well, Let Me In dispenses with it altogether. (I refer you to my review of the Swedish version for an explanation of why I think that’s a good thing.) Secondly, Let Me In makes more and better use of the early-80’s setting than either the previous film or the novel, in which it was little more than an excuse to have Oskar’s Rubix Cube serve as an ice-breaker between him and the puzzle-loving Eli. Let Me In has a much stronger sense of period, with which it makes up to some degree for the environmental shrinkage caused by the winnowing of the cast. Ronald Reagan is constantly on the TV news. The radio plays Greg Kihn, Culture Club, the Vapors, and the Blue Öyster Cult. The kids’ first date, if you can call it that, is at a video arcade. Owen doesn’t just fantasize about turning the tables on Kenny’s gang— he fantasizes about doing so as a Michael Myers wannabe. And in the cleverest period touch of all, the cop leading the investigation of the Los Alamos exsanguination murders leaps immediately to the hypothesis that a Satanic cult— possibly employing ritual child abuse in its sacraments of blasphemy— is behind the crimes. That’s exactly what would have happened under these circumstances in 1983, and it works tremendously as a way to get the detective thinking about things that might lead him to Abby without pushing him so far as to believe in vampires. I’m still not convinced that any of that is enough to justify remaking a top-notch film that’s only two years old, but I suppose Let Me In at least offers those who are allergic to subtitles a chance to appreciate this story.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact