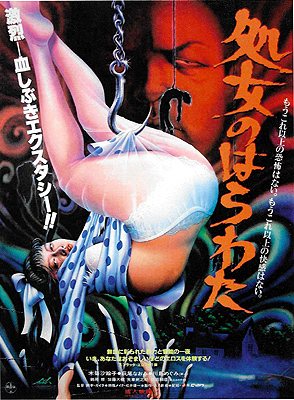

Entrails of a Virgin / Guts of a Virgin / Shojo no Harawata (1986) **Ĺ

Entrails of a Virgin / Guts of a Virgin / Shojo no Harawata (1986) **Ĺ

In the West, we usually like to maintain a boundary between horror and eroticism. To be sure, that boundary is often pretty porous, so that monsters routinely become sexual metaphors or even objects of attraction, but itís rare for it to collapse completely. Like, thereís certainly no shortage of sexy vampires in Western film and fiction, but they tend to look more like Ingrid Pitt or David Boreanaz than Max Schreck or Reggie Nalder, and their fatal kisses arenít normally accompanied by arterial spray. In general, our erotic horror is either sexy (with a bit of spooky spice) or horrible (with sexual anxieties at the root), and only the most transgressive and disreputable artists ever attempt to achieve both effects simultaneously, in a single image, scene, or turn of phrase. In Japan, though, horror and erotica have been allowed to flow into and through each other so completely and so often that the confluence needs a name. Ero-guro, they call itó the erotic grotesque.

The term itself dates to the 1920ís, when Japan was undergoing a phase of headlong cultural liberalization broadly analogous to the more famous one going on in Germany around the same time. (Japanís Taisho-era liberalization came to a bad end not unlike the Weimar Republicís, too, in 1936.) Ero-guro was mainly a literary movement in those days, associated with writers like Rampo Edogawa and Kyusaku Yumeno, and with magazines like Shinseisen (New Youth), but the visual arts got into the mood as well. Because of course they did, because Japanese visual artists had already been doing ero-guro for about 60 years by the time it got dubbed that. As early as the 1860ís, there had been a genre of woodblock prints known as muzan-e, or atrocity pictures, and while many of them were just straight depictions of extreme violence, often in a military context, plenty of others got morbidly kinky, too. Most famously, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, widely regarded as the last great master of woodblock art, included among his contributions to the print series, 28 Famous Murders, with Verses, several images that prefigure ero-guro in its most extreme form as startlingly as Katsuhiko Hokusaiís The Dream of the Fishermanís Wife prefigures the Naughty Tentacles subgenre of hentai anime.

So ero-guro has a history, but if you consider the specific creators I namedropped aboveó Edogawa, Yumeno, Yoshitoshió youíll see that it has a pedigree as well. Those are names that serious students of Japanese arts and letters will recognize, and not just some bunch of knuckledraggers financed by gangsters, catering to the lowliest dregs of society. And the same held true when ero-guro came to the movies in the mid-to-late 1960ís, once Japanís postwar film-censorship regime had relaxed sufficiently to allow fairly explicit depictions of violence and sexuality. Nearly all of Japanís major studios invested heavily in erotic cinema throughout the 60ís, 70ís, and 80ís, and most of them at least dabbled in ero-guro. 1968 seems to have been the watershed year for that sort of thing. Daiei released Womenís Prison, anticipating what would become a worldwide genre in its own right during the following decade. Toei offered Shogunís Joy of Torture, a period-piece anthology film about Tokugawa authority figures doing ghastly things to women. Even Nikkatsu, Japanís oldest and occasionally biggest film company, got into the act that year with Womenís Bathhouse of the Floating World*ó which sounds innocuous enough by that name, but was perhaps more accurately summed up by the title it carried in Italy, Sadistic Violence Against Ten Virgins. As sex films in general became more and more important to Nikkatsuís business model (the company released over 800 of them between 1971 and 1988!), it stood to reason that ero-guro would remain a recurring subtheme of both their own in-house productions, and the independently produced films which they increasingly picked up for distribution as their fortunes declined in the 80ís.

And that, at last, brings us to writer/director Kazuo ďGairaĒ Komizu. Komizu got his start in the movie business in 1967, as an associate of leftist gangster turned filmmaker Koji Wakamatsu. After working on several early Wakamatsu Productions pictures in a variety of capacities (actor, assistant director, still photographer, etc.), Komizu wrote the script for one of the bossís most notorious movies, Go Go Second Time Virgin. He then wrote two more screenplays for Wakamatsu, and directed a film of his own under the Wakamatsu Productions banner, before taking his leave of the firm in 1972. He resurfaced in 1979, writing and directing for a variety of porno studios, ranging from short-lived, rinky-dink outfits like Danei to Kokuei, one of Japanís most important and enduring skin-flick factories. Now as you might expect of a guy who took his nickname from the anthropophagous giant in War of the Gargantuas, nearly all of Komizuís ero pictures were also at least a little bit guro. So no one should have been too surprised when he started making disturbingly sexy horror movies alongside his usual disturbingly violent sex films. Komizuís maiden voyage into his new field was a shot-on-video short called Guzoo: The Thing Forsaken by God, Part I, in which a quartet of high school girls vacationing together at the country home of a favorite teacher are variously stalked, killed, and orally violated by the tentacle monster living in the basement. Guzoo went straight to video, but Gairaís next three horror films were all of sufficient length and professional enough workmanship to be picked up for theatrical release byó thatís rightó Nikkatsu, who at that point were willing to try pretty much anything to keep the lights on another day. The first of these was Entrails of a Virgin, which is much smuttier than Guzoo, while also being comparably strange and gory. Imagine a Fantom Kiler movie with both the stark irrationalism of Takashi Miikeís Gozu and the dreamy arthouse esthetics of Death Bed: The Bed that Eats, and you wonít be far off from the vibe of Entrails of a Virgin.

Asaoka (Daiki Hato, from Climax: Raped Bride and Whitepaper on Passionate 18-Year-Olds: My Favorite Teacher) is a photographer specializing in pinups ranging from the mildly titilating to the openly pornographic. Tachikawa (Hideki Takahashi) is his apprentice, who mostly does stuff like operating the flash gun and keeping track of whatever equipment is needed for a session when it isnít actively in use. Iím not sure what you call people like Itomura (Osamu Tsuroka, of Angel Guts: Red Porno and Semi-Document: Fake Gynecologist) in the photography business, but his role seems to be roughly analogous to that of a producer in the movies. And Kei (Megumi Kawashima) is the model that Itomura is currently pushing. Theyíve all driven out to the country for a photo shoot, accompanied by a pair of makeup artists named Rei (Saeko Kizuki, from Eveís Flower Petal and Female Bank Teller: Rape Office) and Kazuyo (Naomi Hagio, of Pink Curtain and Wife Collector), the latter of whom seems to be studying under the former much as Tachikawa is studying under Asaoka.

All the relationships here are more complex than they appear, however. Kei is dating the photographer. Rei, meanwhile, is one of Asaokaís former girlfriends, and has never really gotten over being callously dumped by him in mid-coitus some unspecified but evidently not far-distant time ago. Kazuyo is conspicuously infatuated with Asaoka as well, apparently turned on by his gruffly commanding demeanor on the job. And Itomura, the bastard, has an arrangement with Asaoka whereby he periodically gets to borrow whatever girl the photographer is currently screwing. Tachikawa, for his part, is disgusted by pretty much all of them except Kazuyo, but lacks the power to act on his disgust in any effective way. All he could do is to walk out, strangling his own career in its cradle without posing more than a temporary inconvenience to Asaoka, Itomura, Kei, or Rei.

Driving back to the city through the mountains after the shoot, the sextet encounter a dense fog bank, reducing visibility to near zero. Combined with the darkness of the night, the density of the woods, and the steepness of the slope on the downhill side of the road, itís obvious that to drive in that fog is just asking for troubleó and indeed Asoka hits something with the van in no time at all. He never saw clearly what it was, but Tachikawa is pretty sure it was a man. They find no trace of anyone when they get out to look, however, although Iím not sure they would under the circumstances, unless the presumed victim were either directly in front of or under the vehicle. In any case, Asaoka and company clearly need to find somewhere to put up for the night, and quickly. The first place they come to is a large, unoccupied house undergoing extensive renovations. The front door is unlocked, and better still, the water and electricity are both in service despite the mess the house is in at the moment. Thereís even food and booze in the pantry! The only question is how to pass the time until the photographer and his associates are ready to sleep. This being the kind of movie that it is, what Asaoka and Itomura ultimately settle on is to heap psychosexual abuse on Rei, Kei, and Kazuyo, using their authority over Tachikawa to lever him into playing along.

What none of these people realize, though, is that something awakened in the swamp at the foot of the mountain when they hitÖ well, whatever it was they may or may not have hit back there. This entity adopts the form of a nude man (Kazuhiko Goda) smeared in black mud over every square inch of his body. And now that itís active, it makes a beeline for the half-rebuilt house, where it proceeds to pick off the people who so rudely disturbed it one by one. And this being the kind of movie that it is, the swamp creature wreaks appalling sexual violence on the women either before or while it kills them, whereas the men are merely bludgeoned with hammers, run through with spears, or strung up and gutted.

For all that Kazuo Komizu professes to have disdained contemporary American horror movies, Entrails of a Virgin unmistakably owes a great deal to them. In plot terms, itís distinguishable from a fifth-rate US slasher movie only insofar as one of those would almost certainly have explicitly revealed that the swamp killer was either the pedestrian Asaoka ran down in the fog or his vengeful ghost, revenant, etc. This movie not only doesnít do that, but indeed never makes it entirely clear whether there ever really was a man on the road, or whether the accident sequence was meant to depict what Asaoka and Tachikawa imagined in their growing unease as they drove through the forest under increasingly hazardous conditions. Nor is that the only time when Komizu makes the audience work to interpret what they think theyíre seeing, either. That comfort with ambiguity goes a long way to elevate Entrails of a Virgin above its sophomorically crass subject matter and crudely minimalist narrative.

Entrails of a Virgin also kept me pleasantly off balance with its frequent recourse to a sort of visual poetry starkly at odds with the grotty misanthropy at its core. I donít mean just the unusual amount of attention that Komizu paid to atmospherics, either. Although the film presents itself (and not unjustly) as a hardcore gore flick, Komizu was surprisingly selective about when and how to live up to that promise. The simple fact is that he had very little money to spend here, while four of the five murders called for in the script would have been quite expensive to show in the expected manneró at least if Komizu wanted to do them right. So what he did instead was to devote the great bulk of his special effects resources to the single most flagrantly outrageous killing, in which the swamp creature pulls out the victimís intestines through her vagina after fist-fucking her. The other murders all got treated very differently. At first glance, it appears that Komizu is employing the perennially popular and economical workaround of cutting away just before the killing stroke, so that he can reveal the aftermath later, when one of the other characters stumbles upon it. In fact, though, heís doing something much weirder and more imaginative. Instead of jumping to some other scene as youíd expect, when the camera averts its eyes here, weíre shown some symbolic representation of the victimís death: a hammer slamming down on a slab of raw beef, a pitcher of water spilling all over the place, etc. Itís as if weíre seeing not the physical facts of all this slaughter, but rather the internal ďdoes not computeĒ signals fired off by the charactersí dying brains at the moment of expiration. Gorehounds will be annoyed, I expect (which I concede is rather a big problem for a movie like this one), but I almost always enjoy it when someone sidesteps the obvious solution in favor of something Iíve never seen before.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact