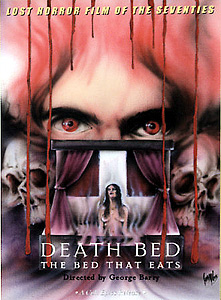

Death Bed: The Bed that Eats (1977/1983/2003) -***½

Death Bed: The Bed that Eats (1977/1983/2003) -***½

Writer/director/producer George Barry never managed to secure a distribution deal for Death Bed: The Bed that Eats, at least not when there was any pressing need for him to do so. That’s really very impressive when you think about it: he somehow found it within himself to make a movie that was too weird for the 70’s! It becomes slightly less difficult to believe once you watch Death Bed for yourself, as it truly is a challenge to imagine the natural audience for a horror movie paced and structured like an art film, in which both the monster and the hero are inanimate objects, and which could equally well have been intended seriously or as the most deadpan of black comedies. Barry spent three years or more shopping his odd little movie around without a single taker before learning his stern lesson. Then he stuffed Death Bed into the closet and got on with his life, never again trying his hand at a feature film so far as I can determine. Somebody must have seen merit in the picture, though— perhaps a technician at the lab where the answer print was struck in 1977, or one of the projectionists who screened it for some unimpressed regional distro chieftain during its doomed marketing campaign. I say this because in 1983, an unauthorized print turned up in the UK, making the rounds of whatever Britain’s equivalent to the drive-in and grindhouse circuits was in those days. A second pirate copy surfaced in Spain two years later, and the very faintest whisper of word-of-mouth buzz began to surround Death Bed: The Bed that Eats in Europe. Barry, let us be clear, had no idea any of that was going on. Now flash forward some twenty years. Barry finds himself up late one night, perusing the forums at Scarlet Street, when his eye lands upon a thread whose initiator is seeking information— any information, really— about a horror movie so mysterious and improbable that he can barely believe it exists at all. That’s right— it’s Death Bed. I would love to have been there to see the look on Barry’s face. Thus began a quest by the flummoxed filmmaker to discover how on Earth a picture he had never been able to sell, which to the best of his knowledge existed nowhere outside his own possession, had developed the tiniest of cult followings. Thus also began a second attempt to make at least a few bucks on the thing for himself, an attempt which happily culminated in Death Bed: The Bed that Eats receiving legitimate release on DVD fully 26 years after its completion. Amazingly, it was almost worth the wait! (To the extent that anyone ever realized they were waiting, that is…)

Once upon a time, there was a demon who lived in a tree. It’s boring being a tree, though, so one day the demon turned himself into a wind and went exploring. While out and about, he saw a human girl with piercing gray eyes (Linda Bond) and fell instantly in love with her. The demon blew himself all over and around her, passing his ethereal body through her hair and under her clothes and across her skin, but it simply wasn’t enough. The fiend’s passion would not be sated by anything less than mutually carnal contact, so he took human form and then conjured up a bed fit for an empress in which to romance the girl. Even then there was one rather serious problem, for although the object of the demon’s affections surrendered herself willingly to his overtures, the fact is that infernal and material physiologies are just not compatible. The girl died of the demon’s lovemaking, even as enough of his immortality rubbed off on her to render her corpse incorruptible forever, and to trap her soul within it in a state of dormancy. The demon was distraught, and wept tears of hellish blood all over the bed that he’d created before returning to his tree, never to emerge again.

The girl had family, of course— a large and wealthy family who lived in a beautiful mansion far out in the country. Eventually they found her, and brought her body home for interment in their private cemetery along the bank of a lazy stream. Unfortunately for them, they also brought home the bed in which the dead girl lay, incorporating it among their own similarly lavish furnishings. I call this unfortunate because the demon’s blood had imparted life to the bed, together with a sort of dull cunning, and because those attributes came from a demon, it was inevitable that they would be put to the service of evil. The bed killed and ate everyone who lay down upon it, exterminating first the family and then the associates of each person who acquired the property thereafter. The house and its grounds took on an ever more sinister reputation, often sitting unoccupied for years at a stretch. Eventually no one could be persuaded to buy the place, and the asking price for rental dropped so low that it came within the reach of an artist (David Marsh, with the overdubbed voice of Patrick Spence-Thomas) in search of a peaceful and aesthetically pleasing venue for the final stages of his losing battle with consumption. The bed would not eat this tenant no matter how long he lay in it— I mean, ew. Starving artist in tuberculosis sauce? Even creatures from Hell have some standards! Nevertheless, the evil of the house still ensnared him, for his last drawing was a portrait of himself in his demon-possessed deathbed. The triangle of mystical connections thereby established was such that the artist’s spirit became imprisoned in the drawing— which has hung ever since on the wall across from the killer bed, affording him a grimly perfect vantage point from which to observe its continued depredations. The bed is also the only being with whom the captive shade can communicate, except during the brief period once each decade when the demon in the tree goes to sleep, bringing the bed’s power to a sympathetic ebb. Then and only then can the artist manifest himself in a manner visible or audible to the human world.

The thing is, we won’t know about any of that until the movie is almost half-over! All we know when the legend, “Breakfast,” announces that the pre-credits teaser sequence is about to begin in earnest is that there’s a stuffily Byronic-looking guy sitting in a tiny alcove hidden behind a wall-mounted drawing, glowering at the huge canopy bed that dominates an otherwise austere room and complaining that he’s spent most of the last 60 years listening to the thing snore. That’s right. The bed snores— oh yes it does. Anyway, “Breakfast” refers to a young couple who aren’t half as young as they’re probably supposed to be (Marshall Tate and Dessa Stone) snooping around the mansion’s somewhat overgrown grounds. Evidently the male half of the couple has convinced his paramour that the old house would be a great place for a sex picnic. Their arrival rouses the bed from its slumber, and it uses its powers of telekinesis to bolt all the doors into the mansion proper, so that only the outbuilding to which it was transferred after the place was briefly taken over by a quack impotency clinic (it’s a long story…) remains accessible. The couple let themselves in, spread out their food on the coverlet, and begin making out. The bed first helps itself to their apples, fried chicken, and wine, and then devours them too. Apparently it’s still hungry, though, because immediately thereafter, it throws a telekinetic temper tantrum which the ghost in the portrait eggs on until the whole main house is demolished— off-camera, of course. Why do I get the feeling that detail was hastily written in when George Barry learned at the last minute that he wasn’t going to be allowed more than a single day’s shooting at the mansion location?

After a deeply bizarre interlude in which the bed dreams that it has been moved to a big-city hotel (the accompanying 40’s-style newspaper headlines are one of the very few hints Barry ever drops that he might actually be kidding us), we cut to three young women driving down a country road. Their leader, Diane (The Temp’s Demene Hall), is a friend of the lawyer whose thankless job it is to manage the legal affairs of Death Bed Manor, and it was from him that she apparently found out about the place— which of course she and her friends won’t be seeing now that the bed has torn it down. The reason for the trip is rather mysterious, but the next half-hour makes the most sense if we assume that Diane and Sharon (Rosa Luxemburg— no, really) are lesbian lovers sneaking off for a get-together away from disapproving eyes. Certainly that’s the best way I can think of to account for why Sharon’s mother has dispatched her older brother (William Russ, from The Unholy and American History X, billed as “Rusty Russ” here) to track her down and bring her back home. The third girl, Suzan (Julie Ritter), is one of Diane’s coworkers; from the sound of things, the other two sort of wish she wasn’t there, but Diane didn’t have the heart to say no when Suzan found out about the trip, and asked to be brought along. In any case, Suzan keeps to herself while the other two prowl the property trying to figure out how it’s possible for a fucking mansion to go missing, moping about how she should never have horned in on the venture in the first place. Eventually, she retreats to the still-intact out-building, and lies down for a nap. That makes her “Lunch,” but not until after the bed has amused itself for a bit by sending her dreams about being made to eat bugs.

I’m sure it’s obvious at this point that either Sharon, Diane, or possibly Sharon’s shaggy-haired brother is destined to be “Dinner,” but it quickly becomes equally obvious that the next meal is likely to go a bit differently than the others. The bed is terrified of Sharon, you see, so much so that it develops ulcers. That gets the ghost of the artist thinking, and eventually he makes the connection that Sharon’s creepy, gray eyes must remind the bed of its “mother”— that is, of the supernaturally preserved, dead-but-still-fully-ensouled girl whose fragility in the face of demon-cock is ultimately responsible for the bed’s malign sentience. That in turn leads the artist to suspect that she could be the person he’s been hoping would arrive for some time. Don’t ask me how, but the ghost in the drawing knows a magical rite that will free both him and the dead girl from their respective limbos and destroy the bed, and that demon in the tree is long overdue for a nap. If Suzan can just keep herself from getting eaten until the fiend falls asleep, he could contact her and set the process in motion at long last.

So you see what I mean, right? If ever there were a movie that no one was going to want to see, Death Bed: The Bed that Eats looks like a fair enough contender for the title. What the distributors of 1977 failed to realize was that that itself could— and ultimately would— become an affirmative draw for people of a certain type. It’s just a matter of knowing who your customers are. Of course, it’s entirely possible that the audience Death Bed needed didn’t yet exist in 1977 on a scale sufficient to make back the money that was spent on it, but I don’t really believe that. The very fact that pirate copies escaped into circulation shows that somebody out there had more vision than any of the moneymen Barry talked to about distribution, and Death Bed’s success in accruing a cult following on the basis of what appears to have been two lousy prints demonstrates the validity of that vision in the face of every seemingly sensible objection.

Death Bed: The Bed that Eats is a film that I find myself appreciating more and more the longer I think about it. My initial impression was that it was merely a misbegotten folly, but while I still believe that to be a more or less fair characterization, I also increasingly see commendable hints of a Frank Henenlotter sensibility at work in it— of a desire, however imperfectly realized, to play fair with and to do right by a concept so crazed that it seems fit only for comedy. To be sure, there is some obviously deliberate levity in Death Bed. I’ve already mentioned the parody of the old newspaper headline routine during the bed’s dream of moving to the city, and the flashback sequence about the impotency clinic is unintelligible except as a foray into sick farce. There’s also a bit where the bed absorbs Suzan’s purse so that it can drink her Pepto Bismol in the hope of soothing the ulcers caused by its superstitious dread of Sharon. But mostly, Barry treats this strange and silly story as if he really means it, and while a lot of his choices are more than questionable, a few are also clever and fairly effective. You might ask, for example, how exactly one depicts people being eaten by a bed. Whenever the bed absorbs something into itself, the camera cuts to an internal perspective, showing the enveloped object floating in a body of corrosive yellow fluid. It makes for a few really striking images, and for some very impressive low-budget gore (often both at the same time). Barry also succeeds from time to time in creating a dreamy atmosphere that dovetails nicely with the fairy tale-like origin stories of the killer bed and the sentient drawing. He is unsurprisingly let down by all of his actors (no fortuitously good-bad Kevin Van Hentenryk in this cast), and the languid pace and insistently non-linear story structure are occasionally unhelpful. Nevertheless, I can’t help but be won over by a movie that takes a premise so utterly bonkers, and then really puts its back into it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact