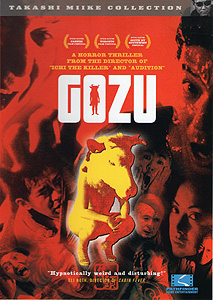

Gozu / Yakuza Horror Theater: Gozu / Gokudo Kyofu Dai-Gekijo: Gozu (2003/2004) ***

Gozu / Yakuza Horror Theater: Gozu / Gokudo Kyofu Dai-Gekijo: Gozu (2003/2004) ***

Even in a country justly noted for its defiantly weird movie industry, Takashi Miike has developed a reputation as a defiantly weird filmmaker. And while I have seen very few of his shockingly numerous movies (he averages better than four per year over a career reaching back to 1991), I get the distinct feeling that Gozu is an extremely peculiar movie even for him. Though it is most commonly classed as a horror film, and though its initial setup would qualify it as a crime drama, it is in fact something to which conventional notions of genre or category are almost completely irrelevant. Best perhaps to say that Gozu is a fever-dream set down on celluloid, and leave it at that.

Ozaki (Sho Aikawa, from Peking Man and Séance) is a small-time yakuza operative, controlling the affairs of a little plot of territory with the aid of his protégé, Minami (Miike regular Hideki Sone). Ozaki is also insane, although what we’ll be seeing later will raise fundamental questions about what “sanity” could possibly mean in a world where a story like this one can take place. The big boss (Renji Ishibashi, of Watcher in the Attic and Tetsuo: The Iron Man) has called a meeting of his subordinates at the restaurant which Ozaki apparently uses as a front for his illegal enterprises. Ozaki interrupts the discussion of the mob’s usual business to ask if his leader happened to see the dog out front. The boss has no idea what Ozaki means. Ozaki leans forward, and instructs his chief to not to pay attention to anything he’s about to say. He leads the boss and several of the other mobsters out front, points to a couple on the sidewalk who are playing with some pocket-sized, Chihuahua-like pooch, and announces that the animal is a “yakuza-attack dog,” trained specifically to hunt and kill gangsters. Then he goes outside, grabs the dog out of its horrified owner’s hands, and smashes it against the sidewalk, the window, and pretty much every other hard surface that’s handy until it’s little more than a thick, hairy paste.

Faced with such clear evidence that one of his men has gone enthusiastically off the deep end, the boss secretly orders Minami to eliminate his mentor. Minami is to drive Ozaki out to Nagoya, where he will hand the condemned gangster over to a special team of killers who operate out of the city dump. These men will then furnish Minami with proof of Ozaki’s death, and Minami will return home to present it to the boss. All very simple, right? Ha. A little over a kilometer outside of Nagoya, Ozaki commands Minami to come to a halt. You see that white car, the one that’s been right behind them since the last intersection? Well, it’s a yakuza-attack car, specially trained to hunt and kill yakuza! Ozaki crouches down behind the bewildered Minami’s Mustang for a moment, and then charges, pistol at the ready. Minami knocks his old friend out by hitting him from behind with a big rock, and then scares the white car’s stunned driver away. Minami figures that should keep him out of trouble for the rest of the drive into town, but then he hits the river. Without warning, the road Minami is driving simply stops at the cliff-like bank of a small, turbid river; there’s no bridge, and with a good twelve feet of sheer drop on either bank, there can be no question of trying to ford the stream. Minami has no choice but to slam on his brakes, and when he does, the unconscious Ozaki launches forward in his seat and cracks his head against the dashboard (which were not yet generally padded in 1964, when the Mustang was built). On the one hand, this saves Minami and his gang a bit of trouble, as the aim was to kill Ozaki anyway, but the body still needs to be handed over in Nagoya, there’s a river in the way that shouldn’t even be there, and anybody who’s ever seen Weekend at Bernie’s knows what a pain in the ass it is to haul around a dead body in a crowded place. As soon as Minami makes it into town, he sticks a pair of sunglasses on his dead partner’s face in the hope that people will assume that he’s merely sleeping, and pulls in to get himself some head-clearing coffee at a little restaurant.

This is where the trouble really starts. This Coffee Shop of the Damned is operated by a shaven-headed cross-dresser and two robot-like companions, and its sole other customer is an obvious lunatic who sits at a pay phone with about four pounds of ¥10 coins, jabbering incoherently about how it’s cold today, but it was t-shirt weather the day before yesterday. The transvestite waiter brings Minami a “complimentary” cup of chicken custard along with his coffee, and eating it immediately makes Minami puke up his guts. When he emerges from the bathroom, Ozaki is gone from the Mustang’s back seat, and none of the weirdos in the coffee shop will admit to having seen anything. In a panic, Minami calls his boss, catching him in the middle of fucking one of his innumerable girlfriends. The boss keeps right on going while he takes Minami’s call (Minami understandably vagues up the nature of his problem just a little), and suggests that the Shiroyama crew might be able to help him out, giving him an address where they can be reached. The address turns out to be a Buddhist temple instead, and the priest responsible for it reasonably professes never to have heard of a yakuza band called Shiroyama. Without a trace of irony, he recommends that Minami ask the police for assistance, and Minami is so near the end of his tether by that point that he actually takes the old man up on his advice, although the one cop he asks has never heard of any Shiroyama crew either. The frustrated gangster finally locates the Shiroyamas by complete accident. When he blows a tire by driving over a bone, there’s a man named Nosechi (Shohei Hino) sitting beside the road who happens to be one of their agents. Minami doesn’t learn this, however, until after he has spent some considerable while in the strange man’s company, having followed him to a dump outside the city in search of a replacement tire, and spying “Shiroyama Crew” scrawled in spray paint across the rusted-out hulk of a Winnebago. The leader of the Shiroyamas agrees to help Minami, but only if he can answer the riddle, “What takes and also passes?” in 30 seconds or less.

With that hurdle cleared, Minami goes with Nosechi to the Masakazu Inn, where he rents a room from the unnervingly weird owner (One Missed Call’s Keiko Tomita) and her only slightly less unnervingly weird brother, Kazu (Harumi Sone, of Message from Space and Battles Without Honor and Humanity). The innkeepers are an intrusive pair, the woman especially. A scene that unfolds between her and Minami while the latter is trying to take a bath is the very definition of the phrase, “boundary issues.” It would also appear that they have some sort of secret (or quite possible several hundred), and the room which they rent to Minami might perhaps be haunted or cursed or worse. From here on out, Gozu is little more than a meandering string of loosely connected vignettes, in which Minami searches for any sign of Ozaki, with the help and despite the hindrance of a cast of characters who are at best insane, quite possibly dead, and in some cases not even human to begin with. Ozaki and a minotaur-like demon will each appear to him in a dream to give him something that will turn up in bed beside him when he awakens, and he will learn never to accept anything from anyone if it is described as “complimentary.” He’ll also learn to think twice about drinking the milk at family-owned inns in down-and-out bumpkin towns. And when he finally tracks down Ozaki… well, let’s just say the subtext rapidly becomes text after that…

Gozu is about as bent as it gets. Like Eraserhead, it seems deliberately designed to make a mockery of any attempt on the viewer’s part to figure out what’s “really” happening, or to fit the events on the screen into any sort of conceptual framework. The ending, most strikingly, is simply impossible to explain, on any terms. It merely happens, and if you can’t accept that (and I suspect a lot of people won’t be able to), then that’s just too bad. Remarkably, however, a close examination will show that what initially looks like a random succession of ever stranger non-sequiturs is actually nothing of the sort. Though Gozu follows no recognizable narrative logic, it definitely possess a unity of theme and what I would be tempted to call an internal web of meaning, were it not for this movie’s seeming rejection of the entire concept of meaning as that term is generally understood. Everything is significant, everything is interconnected, even if it adds up to the purest irrationality once all the pieces are in place, and it is in this respect that Gozu is most dreamlike— in creating sense out of nonsense, only to become more nonsensical than ever when taken as a whole. Gozu also mimics a bad dream in that it is often deeply disconcerting for no obvious reason. It should be ridiculous when Nosechi comes to Minami, trembling in terror because he has recognized the Pay Phone Guy and his buddy from the Coffee Shop of the Damned as the leaders of the bad kids from his junior high school; instead, Nosechi’s terror is contagious because it is so totally irrational. On the other hand, Gozu is just as apt to be blackly hilarious, as when it is revealed that the sexually insatiable yakuza boss has a fetish so dementedly specific you just know it must actually be attested in some case history somewhere. Unfortunately, this movie is also much too long. No film whose plot basically vanishes into thin air at approximately the half-hour mark can afford to run for 129 minutes, and while it is always interesting to see what screwy direction Miike and screenwriter Sakichi Sato are going to drift off in next, the time eventually comes when even the most patient audience will grow weary of wandering from one disembodied surrealistic freak-out to the next.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact