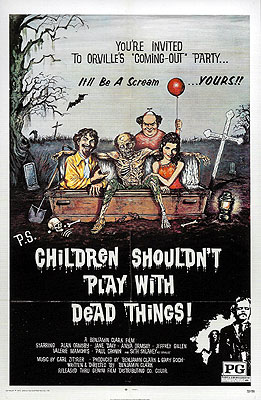

Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things / Revenge of the Living Dead / Things from the Dead (1972) **½

Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things / Revenge of the Living Dead / Things from the Dead (1972) **½

It’s probably fair to say that I like Bob Clark’s Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things more than a sane person has any business doing. The film is as slow-moving as the zombies it depicts, the acting runs the gamut from passable to deeply embarrassing, and every single penny which Clark didn’t have in his budget wound up onscreen. I concede all of those points. But… Let us note, to begin with, that Bob Clark isn’t just any asshole. He also made the pioneering Canadian slasher film Black Christmas— which is regarded by many as second only to Halloween— and the notorious zombie/vampire Vietnam commentary Deathdream. And after leaving the horror genre behind him at the end of the 70’s, he achieved considerable mainstream success by directing the much-loved (if also now grievously overexposed) A Christmas Story. Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things was one of Clark’s earliest movies, and while it’s pretty obvious that he didn’t really know what he was doing at the time, it’s also plain enough that there’s a spark of talent driving this film. Beyond that, Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things was to the best of my knowledge the first North American zombie film inspired by George Romero, and that’s the kind of thing for which I just can’t help but award a few bonus points. Finally, there’s something which Dr. Freex said in his review of this film at The Bad Movie Report: “I swear I went to college with these people.” Now Freex is a good deal older than I am, but there are some subcultures that never seem to go away, and the drama wankers are perhaps foremost among them. I may not have gone to college with the cast of Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things, but I sure as hell went to high school with their descendants (in fact, I dated Terry’s 1991 counterpart for some eight months), and as a consequence, the movie rings true to me in ways that many more technically accomplished zombie flicks don’t. So while I confess to liking Clark’s lumpy and problem-plagued zombie opus far more than it deserves, I also plead extenuating circumstances. I figure I’ll get off with a token fine and a few months’ probation.

You’ve also got to give Bob Clark props for starting the movie off with a nicely stylish and disorienting misdirect. The night watchman (Alecs Baird) of the cemetery which consumes most of the land on a densely wooded little island somewhere notices something suspicious happening in his boneyard. Specifically, there’s a man in a top hat and Dracula cape (Roy Engleman) digging up one of the graves! Obviously the watchman can’t have that, but when he tries to put a stop to the shenanigans, the grave-digger turns around to reveal a rotten-looking face and a set of dentition that matches perfectly with his hat and cloak. A second sharp-dressed revenant (Robert Philip) joins the first after the unfortunate man has been removed from the scene, and assists his partner in excavating the grave. They remove its original occupant (identified on the headstone as one Orville Dunworth) once they have the coffin lid fully exposed, and then the first undead resurrection man lies down inside the vacated casket, which the second proceeds to rebury.

A bit later that night, a boat pulls up to the shore of the island and disgorges six mid-20’s-ish drama wankers. Their leader, Alan (Alan Ormsby, who wrote both Deranged and the 1982 version of Cat People, as well as assisting Clark on the Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things script), is the director of the troupe, and oh my Christ, is he ever a shitbag. If you spent any appreciable fraction of your youth in the company of actors or artists or just about any sort of self-consciously creative type, chances are you’ve met this guy yourself: outwardly far more impressed with himself than he has any reason to be, he secretly uses his smarmy swagger as a shield to cover the inadequacies of which he is really all too well aware. Obviously such a man would not be content as a mere actor, nor could he face the day if he failed to spend every available moment tyrannizing and tormenting his troupe. After all, an actor is nothing but a piece of meat you use to dress your stage— right, Alan? Four of those pieces of meat— Jeff (Jeff Gillen), Paul (Paul Cronin), Anya (Anya Ormsby, from Thunder County and Deathdream), and Terry (Jane Daly, also in Deathdream)— are completely cowed by Alan’s behavior, particularly by the eagerness with which he raises the specter of unemployment in response to any and every assertion of independence. There is one actress in the company who is neither afraid of Alan nor impressed with his bullshit, however. This brave soul is Val (Valerie Mamches), who one suspects is an ex-girlfriend of the director’s, and who was probably the one who took the initiative in ending the relationship, too.

Anyway, the reason Alan and his followers have come to the island is that the director has had what he thinks is a wonderfully transgressive idea, and the only member of the party who would have the nerve to tell him he’s full of shit as usual is rather looking forward to watching him make an ass of himself. If Alan is to be believed, the island was originally a resort for the hyper-rich, but after it fell into disuse (presumably because the city across the water grew until the island stopped seeming remote enough for its clientele’s taste), the land was bought up by the municipal cemetery, which now uses it mainly for interring those who die indigent. The resort building still exists, and remains in relatively good repair, but it has an unsavory recent history— the first caretaker hired by the graveyard folks murdered his family before committing suicide, while his successor went bananas and hanged himself. (Note, incidentally, that this was a good several years before The Shining.) Between the scum of the Earth buried in the surrounding graves and the heavy investiture of evil in the abandoned inn, the island is now the perfect site for practicing diabolical magic, and that is precisely what Alan proposes to do. Inside that big-ass trunk which the director has made Jeff and Paul hump all the way from the shore is a ghastly magician’s robe (pilfered from the costume closet at Alan’s theater, no doubt) and a “grimory”— not a grimoire, mind you, but a grimory. I don’t know if Alan’s mispronunciation was deliberate, or simply a result of nobody involved in the movie’s creation knowing the correct reading, but it’s the perfect touch either way. At the stroke of midnight, Alan and his followers will dig up one of the graves, and Alan himself will read from the book a spell intended to reanimate the dead.

There’s a major complication, though— as I’m sure you’ve already figured out. The grave which Alan has selected is that of Orville Dunworth, the very tomb which the two ghouls already dug up during the opening credits, and thus Jeff and Paul have a surprise in store for them when they pry the lid off Orville’s coffin. But if the joke’s on them, then it’s on us even more so, for no sooner does the one ghoul lunge out of the casket while the other seizes one of the girls than Alan just about pisses himself laughing. The ghouls, you see, are really Roy and Emerson, two more members of Alan’s troupe! Alan really does mean to use the reanimation spell, however, and with that in mind, he has Roy and Emerson fetch Orville Dunworth and drape him over his cruciform headstone. Alan then dons his ludicrous robe and climbs down into the empty grave, where he recites the incantation from the book. The spell, as Val seems to have expected, turns out to be a rather miserable failure, Orville remains as dead as ever, and Alan throws a temper tantrum. Val gives her ex exactly the sort of tongue-lashing he’s been handing out at the slightest provocation all movie long, and then jumps into the grave herself to burlesque the director’s spell-casting in the style of a stereotypical Jewish yenta. Finally, Alan sullenly orders everybody back to the house with the long-suffering Orville in tow, leaving Roy and Emerson to fill up the desecrated grave.

Back at the house, Alan throws what amounts to a big disrespecting-the-dead party, leading his actors in heaping all manner of indignities upon poor Orville Dunworth (and heaping plenty of indignities of his own upon the actors while he’s at it). Eventually, Anya— who has a strong mystic streak, and is the only member of the team to take any of this seriously as anything except an exercise in appallingly poor taste— has a four-alarm wig-out, getting it into her head that the evening’s activities have made Orville extremely angry. She may just be right. While Val, Jeff, and Paul attempt to quiet Anya and begin thinking seriously about heading back to the boat and leaving Alan to fend for himself on the island, Emerson and Roy are confronted with the very thing the director’s spell failed to accomplish. Every grave on the island opens up to pour forth an army of flesh-eating zombies, which chow down on Emerson and the incapacitated night watchman. Roy escapes despite serious injuries, but running back to the old house really doesn’t solve anything. The zombies follow, and Alan and the actors are surrounded in short order.

The biggest problem with Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things is that it’s an 85-minute zombie movie in which the zombies don’t show up until minute 64. Though its main point of reference in plot terms is obviously Night of the Living Dead, it has the structure of a 1950’s monster movie, and the two templates don’t mesh well at all. It takes a nearly superhuman attention span not to give up on Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things well before the arrival of the first true zombies, and it seems to me that your tolerance for the antics of Alan and company will depend almost completely upon how much exposure you’ve had to their real-world doppelgangers. But this movie contains the most convincing portrayal of the artist as manipulative, domineering bastard that I can ever recall having seen, and while I don’t know exactly how much that’s worth, it very definitely is worth something. Also in the movie’s favor are the brief flashes of something akin to quiet brilliance which are scattered throughout its running time. The prologue with the costumed grave-robbers ends on an effectively eerie note, for example, with the camera shut up inside the coffin as Emerson shovels dirt into the grave, recording nothing but utter darkness and the rhythmic thump of the falling earth. Then there’s the wide-angle shot of the cemetery with the animate corpses clawing their way out of every visible grave; it was easily the most ambitious tomb-raising scene ever mounted in 1972, and nothing I’ve seen even tried to match it until The Return of the Living Dead in 1985. Nobody’s calling Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things a classic, and that first hour is undeniably a long, hard slog, but there is indeed a payoff if you’re patient enough.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact