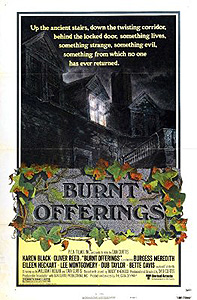

Burnt Offerings (1976) **

Burnt Offerings (1976) **

It isn’t often that you encounter a filmmaker— or at least not one of any noticeable ability— whose natural environment is television, and those who do their best work for TV are even rarer within the horror genre. Dan Curtis, however, is unquestionably an individual of that exceedingly scarce breed. His made-for-TV horror films are deservedly highly regarded, but on those rare occasions when he branched out onto the big screen, the results invariably kind of sucked. Burnt Offerings is much more frustrating than the Dark Shadows movies, simply because there are so many respects in which it is almost good. It has a potentially great cast, a premise that puts a clever new spin on the haunted house scenario at a time when it was already undergoing an enormous conceptual shift, a few moments of exquisite creepiness, and a pleasingly wicked ending employing exactly the kind of aggressive shock tactics that Curtis was enjoined from using on TV. But somehow, those elements never really come together the way they should.

Let’s start by meeting the Rolf family. Ben Rolf (Oliver Reed, from These Are the Damned and Gor) is probably a teacher of some sort, most likely at a college or a well-funded private school. What we know for certain is he’s interested in pursuing some manner of doctorate, that he doesn’t have to work during the summer, and that he’s paid well enough to make the household finances very flexible, albeit not infinitely so. His wife, Marian (Karen Black, from House of 1000 Corpses and Invaders from Mars), has no apparent job outside the home, but her appetite for housework is positively Stakhanovite. Ben and Marian’s marriage seems just a bit strained, although there’s nothing you could point to and say, “Here— this is what’s going to land these two in divorce court if they don’t watch themselves.” Their son, Davey (Lee Montgomery, of Ben and Mutant), is a more or less perfectly ordinary twelve-year-old boy, with nothing really noteworthy about him save perhaps that he entertains athletic aspirations that are just a bit incommensurate with his actual capabilities. As an appendage to the main family unit, the Rolfs also live with Ben’s aunt, Elizabeth (Bette Davis, of Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte and The Nanny). Elizabeth is a spry old lady, her health and vigor making her seem closer to 60 than to her true age of 74.

Anyway, the Rolfs, seemingly at Marian’s instigation, have decided to get out of town for the summer, and rent a nice, peaceful house somewhere in the country until the start of the next school year. Marian has found an advertisement for just such a place, and as the movie opens, she, Ben, and Davey are on their way to check it out and discuss rental terms with its owner, Roz Allardyce (The Bad Seed’s Eileen Heckart). Evidently Roz and her brother, Arnold (Burgess Meredith, from Clash of the Titans and The Sentinel), also want to spend the summer away from home, but that’s all Marian knows thus far. Ben and Marian are taken rather aback when they first set eyes on the house; it’s about five times the size they expected— a real country manor— and its condition is just a shade closer to dilapidated than they would have liked. Also, the owners turn out to be a little batty. Nevertheless, the Allardyces assure their prospective tenant/caretakers that the house requires far less maintenance than it would appear, and that it and its grounds possess glories that are not yet apparent this early in the year— “You should see how it comes alive in the summer!” Roz gushes. And Lord knows the price is right. The $900 figure Roz quotes Ben is not the monthly payment, but the rent for the entire summer. The only catch is that the Allardyces’ extremely aged mother lives in an apartment up in the eaves, and she is far too infirm to accompany her offspring when they vacate the house in June. Ben and Marian would need to look after her. Again, though, Roz and Arnold swear that the burden will be a light one in practice, as the old lady sleeps most of the time, and spends her few waking hours puttering around upstairs with her vast collection of antique photographs. Odds are, the Rolfs will never even see her in the main part of the house. Ben, thinking ahead to all the millions of things that could go wrong attendant upon accepting responsibility for an ancient invalid, finds the terms too onerous, and the Allardyces give him the creeps with their insistence that he and his family must love the house as its owners do, but Marian is smitten, and will countenance no other course of action than to move in as soon as possible.

Things turn weird almost at once. Roz and Arnold ship out before the new tenants arrive, and their mom will not emerge from the locked bedroom in her loft even to say hello. As advertised, the house proves much easier to clean and rehabilitate than seems quite possible; true, Marian and Ben apply themselves to the work with great vigor, but anybody who’s seen Christine will find the speed of their progress most suspicious. (For whatever it’s worth, Ben finds it a little unnerving himself.) But more important than any of that are the changes that all three adult family members begin to undergo after just a short time in the Allardyce place. Ben resumes having a recurring nightmare that plagued him throughout his youth— something about a sinister, smiling hearse-driver (Anthony James, from Howling IV: The Original Nightmare and World Gone Wild) at his mother’s funeral— and has a frightening episode while he and Davey are roughhousing in the backyard swimming pool one afternoon. Something comes over Ben as he and the boy are splashing around; the game turns angry and violent, and Davy is able to escape being drowned only by punching his father in the nose and thereby shocking him back to his senses. And as Ben explains to Marian with intense horror later, it was no mere matter of horseplay getting out of hand. For reasons he can’t articulate, he found himself overcome with disgust for his son, wanting with inexplicable intensity to hurt him. Marian, too, begins experiencing surges of unaccountable loathing, only hers are directed at Ben and Elizabeth. She doesn’t want him to touch her, and she reacts with violent distaste whenever he attempts to initiate sex. As for Elizabeth, Marian loses all patience with her, treating her as a doddering old fool. What’s more, such treatment seems alarmingly to be becoming warranted, for Elizabeth begins aging rapidly almost the moment she takes up residence at the Allardyce house. Within perhaps a month and a half, she’s nearly as feeble and senile as the mysterious Mrs. Allardyce herself.

Then come the more overt, haunting-like manifestations, as the house— true to Roz’s word— really does come alive. Marian becomes practically possessed by her commitment to the house and its reclusive upstairs occupant, spending nearly all her time in the loft’s sitting room, looking over the old lady’s photographs and listening to her antique music box. Davey is nearly gassed to death in what could be either an accident with the radiator in his room caused by Elizabeth’s escalating dementia or an attempt on his life by the house itself. Elizabeth dies in a manner as agonizing as it is inexplicable, and the family’s efforts to save her are obstructed by both a sudden malfunction of the phone lines and an intrusion of Ben’s recurring nightmare into his waking consciousness. Finally, Ben catches the house literally repairing itself, and decides that enough is enough. He determines to get his family out of the house at once, but the attempt is thwarted first by Marian’s refusal to go along, and then by what I can describe only as an attack on the family car by the trees lining the driveway after Ben grabs Davey and sets off without his wife. You see, in contrast to most malevolent horror-movie houses, the Allardyce place wants the company, and it has big plans for Marian in particular.

No, I’m not really sure what the title is supposed to mean, either. Certainly the whole Rolf family has been duped into offering themselves in sacrifice to an acquisitive supernatural force, but at no point is anything ever burned by anybody. My best guess is that calling it Burnt Offerings was a bid to seduce the audiences that were then flocking so profitably toward movies like The Omen and The Exorcist. If the 70’s vogue for cinematic Satanism was strong enough to make even Hammer Film Productions try to milk it, then surely it had the power to inspire a misleading title or two. But those who come to Burnt Offerings looking for fashionable diabolism will get instead something like the prototype of every haunted house movie for the next ten years or so. Hollywood hauntings in the post-Vietnam era differed subtly but significantly from their predecessors, especially as regards the relationship of the typical protagonist toward the malign real estate. The traditional spookhouse is shunned and abandoned; the characters are either aware of its reputation, or quick to perceive the likelihood that it has one; and the house represents primarily a puzzle for them to solve— are there really ghosts within its walls, and if so, what do they require from the living in order to rest in peace at last? The newer school, on the other hand, actively pits the living and the dead (or the mortal and the supernatural) against each other for possession of the property, and the haunting itself manifests not as a mystery to be disentangled, but as an attack to be survived. Openly disregarding the conventional wisdom that a ghost can do no direct harm to the living (or sidestepping it by making the haunter something else altogether), movies on this model raise the stakes considerably. Meanwhile, the enhanced danger for the protagonists is further compounded by their own much greater investment in the paranormally polluted house, for these are no stranded travelers or itinerant investigators of the unexplained. Like the Rolfs in this movie, they can be counted upon to have at least a several months’ commitment to the haunted dwelling, and in all probability, they’ll have taken out a mortgage on it. And perhaps most significantly, the haunted house of the 70’s and 80’s generally looks at first like a dream come true— or at least like too good a deal to be turned down. Maybe it’s available for a fraction of its market value, like the Allardyce house or that famous Dutch colonial on Amityville’s Ocean Avenue. Maybe it comes completely unencumbered by the usual monthly payments, like Sally’s inherited manse in Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark or the Freelings’ Cuesta Verde lend-leaser in Poltergeist. Or maybe taking up residence in the Bad Place seems to offer the solution to some other problem in our heroes’ life circumstances, as when Jack Torrence signs on as the Overlook Hotel’s winter caretaker in the hope of finally getting sufficient peace and quiet to finish his stalled-out book. That last aspect of the transformation in the genre explains, I think, why it took firm root when it did, for it was in the 70’s and 80’s that middle-class homeownership— long a cornerstone of the American economic structure— became a major source of unease, as galloping inflation and stagnating wages combined to push suburban real estate beyond the reach of many people who could easily have afforded it ten or even five years before. Although Burnt Offerings doesn’t push those buttons of economic anxiety as determinedly as, say, The Amityville Horror, the Incredible Shrinking Middle Class is nevertheless an obvious part of the movie’s subtext, and while it was by no means the first film of its type (scattered examples can be found at least as far back as 1944’s The Uninvited), Burnt Offerings came near enough to the beginning of the 70’s-80’s cycle, and bears so much detailed resemblance to so many later, more famous movies that it seems fair to credit it with a great deal more influence than its present obscurity might imply.

That makes it doubly unfortunate that Burnt Offerings is such an uneven, underdeveloped film. The subplot involving Ben’s nightmares about the hearse-driver offers the best illustration of how the movie goes wrong. The nightmare scenes are invariably creepy as hell, but we never do find out just what the whole strange business is about, and the moment when the driver seems to show up in the real world to claim Elizabeth beggars comprehension almost completely. I assume it’s supposed to be an allegorical hallucination on Ben’s part, but the way it pops into the story with next to no warning renders it terribly confusing at the time, and once it becomes clear that neither the dreams nor the hallucination are ever going to be mentioned again, you really do have to ask what the point had been. Similarly unexplained are the specific angles of attack which the house takes against each individual occupant. What goes on with Marian makes sense, and her role in the climax comes as confirmation rather than revelation, but the rest of the family is not treated so sensibly. Mainly, there’s no apparent unifying theme to the house’s attacks on Ben, Davey, and Elizabeth, nothing that would serve to create an overall picture of the nature and power of the entity that inhabits it. How and why does it make Ben try to drown Davey? Is there something in their relationship or in Ben’s past that makes him vulnerable to the Jack Torrence treatment? And if so, why the hell aren’t we notified? What enables the house to accelerate Elizabeth’s aging to a lethal pace, and what, exactly, is she dying from when the man in Ben’s dreams comes to finish the job? To a certain extent, keeping the audience as deeply in the dark as the characters is a potent technique for communicating dread, but Burnt Offerings consistently goes beyond that extent, intimating that Curtis and fellow screenwriter William F. Nolan don’t know what’s going on, either.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact