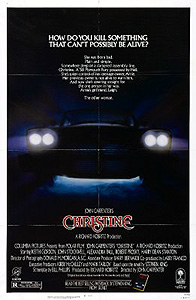

Christine (1983) **

Christine (1983) **

My original plan had been to review Christine as part of the previous update, the one devoted to Stephen King movies that don’t suck. Then I watched it again— let’s just say that my decade-old memories, and the assessment of the film’s quality that followed from them, proved to be rather at variance from reality. That being so, it shall fall to Christine to kick off the Stephen King Suck-a-Thon instead.

Actually, that might not be completely fair, as Christine is not so much notably bad as it is stunningly mediocre, the obvious product of its creator’s inability to come to grips with the novel on which it was based. Christine was yet another example of the early-80’s vogue for major-studio horror movies directed by filmmakers who made their names working outside the studio regime. This time around, the studio was Columbia Pictures and the outsider director was John Carpenter. The film was a work-for-hire project, pure and simple, and Carpenter has openly admitted that he never understood either the appeal of Stephen King’s novel, or what exactly was supposed to be scary about a haunted Plymouth. His incomprehension is evident throughout the movie, which is competently shot, composed, and edited, yet smacks of winging it at practically every turn.

Arnie Cunningham (Keith Gordon, from Jaws 2 and Dressed to Kill) is not cool. In fact, he’s about the farthest thing from cool that has ever walked the hallways of an American high school. He has ugly and unflattering glasses, a bad complexion, worse hair, no athletic prowess, no luck with girls, and significantly more intelligence than his peers consider seemly in a teenage boy. His parents (Robert Darnell, of Malibu Express, and Christine Belford) dominate his life almost completely, his mother especially. He gets picked on constantly at school, particularly by Buddy Repperton (William Ostrander, from Stryker and Red Heat) and his band of low-wattage goons. In fact, just about the only things stopping Arnie from being the perfect textbook nerd are his extraordinary skill as an auto mechanic and his unexpectedly close friendship with Dennis Guilder (John Stockwell, of Radioactive Dreams and My Science Project), the star of his high school’s football team.

The 1978-1979 school year opens on a pair of curiously intense notes for Arnie. Cunningham has shop class right before lunch, putting him into close contact with Repperton and his boys. While Moochie Welch (Malcolm Danare, from Popcorn and The Curse), Richard Trelawney (Island of Blood’s Steven Tash), and Don Vanderberg (Friday the 13th, Part 2’s Stuart Charno) block all potential paths of escape, Buddy seizes Arnie’s lunch, and attempts to goad him into a hopelessly one-sided fight. Odds are this sort of thing has happened often enough to Arnie over the years that he has developed his own name for it— you know, something like “Tuesday”— but on this particular occasion, the stakes climb a great deal higher than they ever have before. Buddy pulls a switchblade on Arnie, and Dennis (who intervenes as soon as he hears that his friend is in trouble again) is unable to talk Repperton down. In fact, Moochie Welch moves in on Dennis to prevent him from coming to Arnie’s rescue, and it takes Mr. Casey the shop teacher (David Spielberg, from The Henderson Monster) to prevent the situation from escalating all the way to serious bloodshed. Repperton gets expelled, and his three accomplices are put on administrative probation. Something even more significant happens on the way home from school. While Guilder drives Cunningham home, the latter boy excitedly demands that his friend stop the car and back up so that he can look again at something he spotted through the rank weeds that pass for the lawn around a catastrophically dilapidated shack. The object of Arnie’s sudden interest is a 1958 Plymouth Fury, and “catastrophically dilapidated” would be a pretty fair description of the car, too. Its red-and-white two-tone paintjob (in the real world, all 1958 Furies were painted a rather lame Buckskin Beige overall) has faded and oxidized to a muddy orange and the dull yellow of decaying teeth; most of its chrome trim (real ‘58 Furies had ugly gold-anodized brightwork instead) has rusted away or just plain fallen off; the windshield is filthy and spiderwebbed with cracks; and God alone knows what must be wrong with the old Plymouth, mechanically speaking. Nevertheless, Arnie is smitten. He wants that car, and he won’t let Dennis take him home until he’s bought it from George LeBay (Roberts Blossom, of Deranged), the broken-down recluse who effectively inherited the ancient Fury when its real owner— his older brother, Roland— died a short while ago. Along with the title and the junker itself, LeBay passes along the name his brother had bestowed upon the machine— Christine.

Christine is no ordinary car, even leaving aside her decidedly non-standard coloration. First, one factory hand was maimed and another killed while assembling her back in the fall of 1957. Then, Roland LeBay’s daughter choked to death while riding in her back seat. Finally, Roland himself committed suicide by running a hose from her crumbling exhaust pipe into the passenger compartment, gassing himself to death behind the wheel. The site of the old man’s suicide seems reasonable enough, for George will later tell Dennis that Christine was the only thing his brother (whom he characterizes as having been even meaner and crankier than himself— quite an achievement if it’s true) ever loved. But for the moment, neither Arnie nor Dennis knows any of that stuff. Right now, Cunningham’s main concern is to hang onto the car in the face of his mother’s disapproval, and to find somewhere to keep Christine when his parents refuse to let him park her anywhere within sight of the house. Arnie winds up taking her to the do-it-yourself repair garage owned by Will Darnell (Robert Prosky, from The Keep), where he manages to endure Darnell’s abuse for long enough to arrange Christine’s long-term storage and permission to scrounge for parts in the junkyard out back.

The plot basically splits into three parallel threads at this point. As Arnie repairs Christine— much more rapidly and effectively than ought to be possible, even for him— the rest of his miserable life seems to sort itself out, too. Darnell acquires a grudging respect for him, and hires him as a sort of combination mechanic and personal assistant. Arnie becomes more assertive, finding a will and ability to stand up for himself that he has never possessed before. Even his appearance changes for the better; his complexion improves, he starts dressing more stylishly and trades in his slicked-back geek-do for a late-70’s interpretation of a rock-and-roll pompadour, and even his hideous glasses inexplicably fall by the wayside. While all that’s going on, Dennis attempts, with a startling lack of success, to court the new girl in school, Leigh Cabot (Alexandra Paul, from House of the Damned and the 1995 version of Piranha), who has been turning the head of every boy in town since she arrived at the beginning of the term. Finally, Buddy Repperton devotes his greatly expanded leisure time to thinking up ways to get back at Arnie for getting him expelled. Not that Repperton misses the old high school grind, mind you— it’s just the principle of the thing. The three strands come back together at the high school’s homecoming game, when Dennis sees to his astonishment that Arnie has arrived in an essentially good-as-new Christine, and with Leigh Cabot, of all girls, on his arm. Indeed, his astonishment is such that he allows himself to get tackled extra-hard, winning himself a hospital stay that will put him out of action until after the New Year. Buddy Repperton (watching the game from the other team’s bleachers and pointedly cheering his erstwhile school’s setbacks) notices Arnie, his car, and his girlfriend, too, and Moochie Welch volunteers the information that he knows where Cunningham keeps Christine.

Guilder’s confinement to the hospital is doubly unfortunate, in that it prevents him from seeing more than fleeting glimpses of the weirdness that now starts erupting around Arnie and his car, or from doing anything about what little he does see. Leigh is the first to have a brush with Christine’s supernatural malevolence. While she and Cunningham are on a date at the local drive-in, an odd scene develops between the two of them, hinging on Leigh’s jealousy of the car and Arnie’s fixation upon it— a jealously which Arnie’s actions underscore even as his words refute it. But more importantly, Leigh becomes convinced that Christine is also jealous of her. As the couple’s argument is winding down, Christine’s windshield wipers seize up and Arnie rushes outside to try to get them working again. That’s when Leigh begins choking on her popcorn, and at just that minute, Christine’s interior dome light flashes on with impossible brilliance, the radio begins blasting some raucous old 50’s greaser anthem, and the car’s doors suddenly won’t seem to come unlocked. Leigh very nearly dies, and in the aftermath, she tells Arnie that she isn’t riding in that car again, skating right up to the edge of issuing an ultimatum to the effect that either Christine goes or she does. Arnie’s contemptuous reaction worries her enough that she goes to Dennis, tells him about her terrible experience, and shares with him her impression that Arnie is changing in frightening ways. Leigh’s near-miss is not nearly so alarming as what follows after Moochie leads Repperton and his gang to Darnell’s garage in the middle of the night to vandalize Arnie’s car, though. The boys trash Christine almost as thoroughly as Darnell’s car-crusher could, but Arnie refuses to accept that that’s the end of her. And no sooner has Cunningham obstinately taken up his tools to repair the obviously hopeless damage than Christine begins magically fixing herself. During the days and weeks to come, Christine also takes to driving herself, hunting down and killing both those who attempted to destroy her and anyone else who seems poised to discover her secret. Rudolph Junkins (Harry Dean Stanton, from Alien and Escape from New York), the detective assigned to investigate the sudden spate of vicious hit-and-run slayings, knows something weird is going on, and that Arnie Cunningham is at the center of it all, but he doesn’t seem to be making sufficient headway toward the seemingly impossible truth to protect Leigh and Dennis from the repercussions when their efforts to save Arnie from Christine (and himself) draw them closer to each other at Cunningham’s expense.

The first car that ever belonged expressly to me (as opposed to being a unit of the tri-generational family fleet) was a 1977 Ford LTD that I bought for $500 the summer after I graduated from high school. It was only three years younger than I was, and while it wasn’t quite as ragged-out as Christine is the first time we see her, it was still plenty fucked up. In my eyes, however, it was a thing of beauty in its sheer hideousness, and I very quickly developed a totally unwarranted and irrational affection for the evil-smelling old rust-bucket. There are times when I still miss it, and I miss the slightly less crappy 1973 Cadillac that replaced it even more. Consequently, I completely understand where Arnie is coming from when he is seduced at first sight by the car that Will Darnell aptly dubs “that mechanical asshole” the first time it darkens his door (and fills up his garage with opaque, blue exhaust smoke just like my LTD used to generate). I also regard it as a self-evident truth that an old car almost inevitably develops a kind of inanimate personality over time, and probably for that reason, I find it baffling that John Carpenter should have been at such a total loss to find the hook in a story about an antique automobile that is not simply quirky or ornery, but actively evil. And on a separate but related note, I don’t understand how a person can look at a fin-tailed 50’s land-yacht, hear the growl of its high-compression V-8, and not get a predatory vibe off of it, as if it were some sort of land-going robot shark.

But be that as it may, Carpenter really didn’t get it, and in not getting it, he made a fairly big mess of everything about Christine that didn’t have directly to do with the technical craft of filmmaking. His central and most serious mistake was to abandon Stephen King’s explanation for why Christine is the way she is. In the book, Christine is essentially a rolling haunted house. Like the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, the car stored up negative psychic energy from its occupants— specifically, the cruelty and misanthropy of Roland LeBay— until it attained an unnatural life of its own, the key event apparently being the choking death of LeBay’s daughter in the back seat. The girl was effectively the blood-sacrifice completing the spell. Some part of LeBay continues to inhabit the car, and when Arnie’s personality starts to change in alarming ways after he gets Christine up and running, it’s because his spirit is slowly being assimilated to that residue of LeBay’s. In the film version, Roland LeBay never appears at all, and Christine is shown to be not so much haunted as cursed, inexplicably deadly even before the final touches were put on her at the factory. What makes this change a nearly fatal misstep is that Carpenter has retained most of the plot points from the book that hinge upon the haunting, even though the haunting itself is no more. Fair enough, Arnie changes under Christine’s influence— but why should he change to become more like George LeBay (who has more or less the personality which the book attributed to Roland)? Why should his dialogue and mannerisms begin echoing those of a character whose only connection to the car was to sell it off as part of an effort to make some cash from his no-good brother’s estate? Why bother to have Will Darnell remember knowing LeBay, or imply that he had kept Christine at the garage sometime during the 60’s? These things either no longer matter or no longer make sense under the revised terms of the now-ghostless story, and Christine is weakened considerably by transforming the title character from a spookhouse on wheels into a mechanical slasher.

That gutting of the story’s core also has the effect of undermining what would otherwise have been an extremely potent performance from Keith Gordon, which is all the more unfortunate because Arnie is the only major character to undergo any meaningful development. In Christine, Gordon must remain convincing all the way through an arc which takes his character from the most pitiable depths of geekdom, through a blossoming of newfound competence and self-assurance, and finally into outright arrogance coupled with seething and unfocused rage at the entire human race. He comes very close to pulling it off, too, but since Christine spends very little time on the peak of Arnie’s development, and since there’s no longer any reason for the form his final decline takes, all that effort on Gordon’s part amounts to tragically little. Meanwhile, the relationship between Arnie and Dennis gets short shrift, and John Stockwell’s abilities are pretty thoroughly wasted. The collapse of the boys’ counterintuitive friendship, which had somehow withstood all the buffeting and corrosion that comes naturally with adolescence, is the central tragedy of the novel, but it receives barely a nod here. Meanwhile, Alexandra Paul might as well have been a department-store mannequin for all the movie gives Leigh to do, and the human villains are downright embarrassing. I find it interesting, given that Stephen King’s Buddy Repperton was basically a reworking of the Billy Nolan character from Carrie, that Carpenter’s casting department would hire William Ostrander, a John Travolta lookalike with bigger biceps and even less talent, for the role— but I can’t say I’m surprised to see Ostrander make just as big a hash of the part as Travolta had of Nolan in Brian DePalma’s film version of Carrie. With all that going wrong, Christine is basically left to get by on a couple of very well-composed scare scenes (the stalking of Moochie Welch is especially impressive), a typically brilliant Carpenter soundtrack making judicious use of a good many old rock and roll songs, and the astonishing special effects attendant upon the car’s supernatural repair work. Alas, it isn’t quite enough.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact