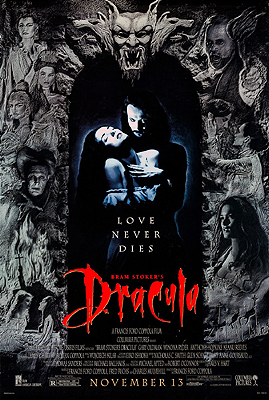

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) -**½

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) -**½

One of my favorite forms of movie ephemera, and the only one that it’s plausibly within my price range to collect at all seriously, is the making-of paperback or magazine touting the supposed virtues of this or that infamously bad film. I’ve got a few such publications for good movies, too, but there’s nothing like reading some freelancer who plainly knows better attempting to work up a head of breathless enthusiasm for the likes of Exorcist II: The Heretic or the Dino De Laurentiis King Kong. One example that I used to own, but lost somewhere along the way, was the behind-the-scenes magazine for Bram Stoker’s Dracula, patient zero in the notorious 1990’s plague of glossy, expensive re-imaginings of classic horror properties that were hysterically desperate to be taken as anything— ANYTHING!— but the fright films they so obviously were. I dearly wish that I could re-read that magazine now, because my dominant memory of it is its step-by-step confirmation that nothing in Bram Stoker’s Dracula was a mistake. The film’s every element, feature, and characteristic may be misguided, dumb, and disastrous, but everything you see here is by all accounts exactly what director Francis Ford Coppola really wanted.

Above all, Coppola was adamant, during the run-up to Bram Stoker’s Dracula’s release, that his was going to be the most faithful version of the oft-filmed story ever attempted. So of course the very first thing he shows us is a prologue sequence set during the 15th-century wars of Ottoman expansion into Europe, which not only appears nowhere in the book, but also sets up an interpretation of the title character antithetical to the author’s. One morning in 1464, Prince Vlad Draculea of Wallachia (Gary Oldman, from RoboCop and Lost in Space) rides out to face what looks on paper like a greatly superior Turkish force. Vlad’s army, outnumbered though it is, breaks the back of the invasion, and as a reminder to any Ottoman soldiers who might march that way again, the prince leaves the battlefield thickly forested with the impaled corpses of his enemies (earning thereby the nickname by which history mainly remembers him). Those Turks, however, sure are sore losers. A survivor of the battle spitefully forges a letter reporting Vlad’s death in action, and that letter reaches the Princess Elizabeta (Winona Ryder, of Alien Resurrection and Lost Souls) before her husband does. Elizabeta promptly hurls herself into the river that courses below the castle’s battlements. Naturally, it’s an uncomfortable surprise for everyone when Vlad returns home safe and sound, only to find his wife broken, bedraggled, and quite thoroughly deceased. I’m not sure that excuses the local bishop (Anthony Hopkins, from Magic and Transformers: The Last Knight), however, when he smugly and tactlessly reminds the bereaved prince that Elizabeta, as a suicide, is inescapably condemned to Hell. Vlad was already pretty pissed off that God would allow such an injustice to befall him while he was actively ramming stakes up infidel assholes in His name, and Elizabeta’s damnation is the final straw. The erstwhile crusader renounces God, drives the clergy from his castle, and performs a ritual of blasphemy that transforms him into a vampire.

433 years later, in London, the law firm for which Jonathan Harker (Keanu Reeves, from Johnny Mnemonic and The Day the Earth Stood Still) works has been engaged to make an extensive real estate buy in the city on behalf of a Transylvanian nobleman by the name of Count Dracula— which doesn’t sound one little bit like Prince Vlad Draculea, right? No, of course it doesn’t. The transaction had been assigned to R. M. Renfield (Tom Waits), but unfortunately the man has gone stark, staring mad right in the middle of the job. By a curious coincidence, the asylum to which Renfield has been committed under the care of Dr. Jack Seward (Warlock’s Richard E. Grant) is right next door to the ruins of Carfax Abbey, one of the ten properties that the lawyer was in the process of purchasing for the count. Renfield’s sudden incapacitation means that Dracula needs a new agent, and Harker’s boss offers him the assignment. It’s a hell of an opportunity, with a huge commission and a chance to impress the senior partners, but it will mean traveling to Transylvania to get Dracula’s signature and seal on the necessary documents. Harker could be gone a long time. It’s something to consider, but the main thing that might stop Harker from taking the job is also his strongest motivation for accepting it: Mina Murray (also Winona Ryder), his fiancée, whom he’d like to marry as soon as possible. Count Dracula’s money could go a long way toward establishing a foundation on which Jonathan and Mina could build their life together.

You know the old saying about no battle plan surviving first contact with the enemy? Well, the longer Harker spends in Transylvania, the less likely it looks that his marriage plans are going to survive this trip. For one thing, the country itself is a lot more hostile than Jonathan was expecting. It’s primitive, remote, underpopulated, and overall threateningly wild— the kind of place the Croats call a vukojebina, meaning roughly “where wolves fuck.” Then there’s the carriage which comes to pick Harker up at the Borgo Pass— and more to the point, its silent, superhumanly strong, armor-clad driver, who looks like he took the post as Dracula’s chauffeur only after his Plan A career conquering the world in the name of Planet Zyklon was thwarted by Kamen Rider Black. But Count Dracula himself naturally beats it all. Although he’s still (just barely) recognizable as Vlad Draculea, he’s changed a lot over the centuries. Indeed, I struggle to find adequate words for the impression he makes in his current guise. John Carradine as the dissipated, septuagenarian, cross-dressing “madam” of the world’s most unappealing geisha house, maybe? Or perhaps the oft-mentioned but never seen Great Leader of the ass-headed Intergalactic Anal Probing aliens from that “Kids in the Hall” sketch about UFO abduction? Either way, he’s nothing like scary, but to paraphrase a later and altogether more convincing Dracula, he is strange and off-putting, and one quickly comes to wish he would go away. Harker is thus most unhappy to learn that the count wants him to remain as his guest at Castle Dracula for an entire month, to familiarize him with the language and ways of England. Nevertheless, Jonathan has spent enough time in Transylvania already to know that around here, titled aristocrats are not accustomed to being denied anything, so he meekly submits to the imposition.

Of course you realize that Dracula’s stated reason for extending Harker’s visit is a crock of shit. What he really wants is a steady supply of human blood on which to build up his strength for the journey to London. Whatever’s left once the count’s needs are met can go to the ladies of his harem (Michaela Bercu, Florina Kendrick, and Monica Belluci, the latter of whom went on to Brotherhood of the Wolf and The Matrix Reloaded). Dracula has acquired a new reason to relocate, too, for Jonathan brought with him a cameo of Mina. The second Dracula saw that, he developed a fixation on the idea that his lost Elizabeta had been reborn in this English girl, and accordingly stepped up the urgency of his preparations. Just how much sooner than planned the vampire sets sail is unclear, but the accelerated schedule leaves his captive drained indeed. Luckily for Harker, the three Mrs. Draculas are not nearly as effective at holding him prisoner as their husband, and even on the brink of death, he is able to sneak away one morning, and seek refuge in the nearest village.

Meanwhile, Dracula (now de-aged to resemble Oscar Wilde trying much too hard to seem butch) has ensconced himself at Carfax Abbey, where his proximity keeps Seward on his toes by making Renfield even loonier than he already was. He also takes to prowling the streets at all hours of the day and night in the hope of bumping into Mina. Eventually he succeeds— and what’s more, he succeeds in striking her as only a little bit creepy. Then even the last scraps of Mina’s trepidation blow away, just as soon as Dracula reveals his impressive family title. (The latter introduction inadvertently but inescapably raises the question of why he’s Prince Vlad, but merely Count Dracula.) The next thing we know, she’s completely succumbed to his wooing, and never mind that schmuck off laboring for her future at the other end of Europe. Mind you, we’ve already seen that Dracula is in no sense a one-woman man, so it won’t surprise us when, at the same time as he’s carrying on his affair with Mina, the count also makes a habit of visiting her friend, Lucy Westenra (Beyond the Rave’s Sadie Frost), in the middle of the night to hypno-fuck her in the form of a bigfoot that’s probably supposed to be a wolf man. There’s reason to believe that the vampire regards these concurrent relationships differently, however, for Lucy, unlike Mina, invariably winds up losing a little blood whenever she and Dracula play Legend of Boggy Creek together. Soon enough, Lucy’s health takes enough of a turn to be noticed by all three of her human suitors: the aforementioned Dr. Seward, front-runner Lord Arthur Holmwood (Cary Elwes, from Saw and The Bride), and pinhead American cowboy Quincy Morris (the Outrageous Okona himself, Billy Campbell).

That’s when Mina receives a letter from the clerics who are nursing Jonathan back to health, and remembers that she’s at least nominally engaged to be married. She hurries off at once to Transylvania to join Harker, leaving Dracula with a “dear John” letter that drives him into a frenzy. The count steps up his depredations on Lucy, so that Seward grows sufficiently worried and flummoxed to seek aid from his old mentor, Dutch physician and high-functioning batshit crazyman Abraham Van Helsing (also Anthony Hopkins, although this time there’s no apparent purpose behind the dual casting). The call for backup goes out too late, however. Lucy is circling the drain by the time Van Helsing arrives, and she dies not much later. The elder doctor sees enough of her, however, to recognize her affliction as one in which he has long taken an interest for no obvious reason— the unnatural scourge of vampirism! Naturally the others take some convincing, but it’s fairly persuasive when the dead girl gets up out of her mausoleum, and starts snacking on the neighborhood children. Dracula can’t help but realize that he has clued-in enemies once Lucy is sent back beyond the grave, which makes this perhaps not the best time for the newly hitched Mina and Jonathan to make their return to London. The vampire may be prepared to concede the city as an inhospitable environment, but no way in hell is he going back home without Mina.

I was quite taken with Bram Stoker’s Dracula the first time I saw it, in the company of the closest thing my high school had to a contingent of goth girls. But when I came back the following weekend with a different group of friends, to whose tastes it was less directly calibrated, I realized that I had been too busy looking at the movie that first time to watch it. No longer bedazzled by a hundred forms of visual flimflam, I was able to recognize Bram Stoker’s Dracula for the try-hard turkey that it is. Indeed, even many of the imagery tricks that had so ensorcelled me before stood revealed upon second exposure as both silly and diegetically illogical. Francis Ford Coppola originally conceived the picture as an exercise in primitivism. Even after the studio balked at his plan to shoot it entirely on an empty, undressed set, Coppola remained committed to using no special effects techniques that would not have been available within a few years of the date when the film was set. Everything that couldn’t be built for real on the soundstage was to be rendered with miniature models, forced perspective, stationary matting, conventional animation, and so forth whenever possible. Occasionally— as in the sequence in which the three Mrs. Draculas conjure themselves from the very sheets and pillows of their bed— Coppola even had recourse to the gimmickry of stage magic. About the only concession to modernity was the foam latex makeup appliances used to transform Gary Oldman into Dracula’s Geisha Geezer, Man-Bat, and Fucksquatch guises. As a technical exercise, it’s extremely impressive all around, and when it actually works, it makes Bram Stoker’s Dracula look like nothing else on Earth.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t work very often, save at the level of mere overwhelming excess, and the main reason why is that Coppola let all the designers who worked on the project run totally feral. None of the pieces fit together right, and many of them are ridiculous even in isolation. Consider, for example, the process that gave us Count Dracula, Geisha Geezer. Coppola wanted Harker’s first impression of Dracula to reflect Stoker’s portrayal of the count aging in reverse as he adds vigorous Western European blood to his diet, and to play up the Orientalism of the extinct Wallachian court (which Stoker had also been at pains to emphasize). But when costume designer Eiko Ishioka heard “Oriental,” she understandably thought not “Byzantine” but “East Asian,” and Coppola either didn’t know enough or wasn’t thinking clearly enough to correct her. Thus we end up with Dracula lounging about his ruined Carpathian castle in a silk kimono with a train as long as any wedding dress, his hair done up in both the sculptured coif of an Edo courtesan and over two feet of Manchu pigtail. Remarkably, Ishioka afforded the count only slightly more dignity as a young man and a Knight of the Order of the Dragon. Prince Vlad’s armor, although intended to suggest a flayed wolf-man, really just leaves him looking like he’s clad head to toe in melted-together Twizzlers. The latter is but one manifestation of another pervasive design problem in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which is that practicality was simply never a concern anywhere. So long as a thing looked cool, Coppola seems not to have cared whether it made any sense in its supposed function. Witness Castle Dracula, built in the shape of a man sitting on a throne, and wanting so desperately to be spooky that it loses all utility as a base of operations for late Medieval warfare.

Casting is another place where practicality clearly never entered consideration. Seriously, who the fuck thinks it’s a good idea to cast the kids from Heathers and Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure as bourgeois Victorians?!?! Who thinks, “You know who’d make a great Renfield? That scratchy-voiced honky blues nutter who sings ‘I Don’t Wanna Grow Up’?” Who goes in search of the definitive Count Dracula, and returns beaming with pride holding a contract signed by the guy who played Sid Vicious? About the only casting decision that wasn’t unreasonable on its face was to put Anthony Hopkins in the role of Van Helsing— and Hopkins is the only actor in the film whose performance is both memorable and more or less okay. I do want to give Oldman some credit, however, insofar as it’s plainly not his fault that he’s awful. His problem is that Dracula here is a fundamentally incoherent character, variously required to be both romantic antihero and embodiment of absolute evil, Promethean sexual liberator and source of spiritual contagion, ultimate fantasy boyfriend who’ll “cross oceans of time” to reunite with his beloved and callous rape-monster who’ll kill his beloved’s best friend slowly and painfully without ever thinking twice about it. Oldman did his damnedest to give Coppola every mutually irreconcilable thing he wanted, even when that meant sim-banging Sadie Frost on top of a crypt while made up as the Abominable Snowman.

And with the incoherence of the title character, we’re finally beginning to close in on the central failure of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Coppola didn’t just want to have it both ways— he wanted to have it all the ways. He wanted his Dracula to be the final word on the subject and the most faithful ever mounted, but he also wanted to pay tribute to everything he enjoyed in every previous version, while also showing for the first time aspects of the story that even Stoker only sort of vaguely hinted at. When we’re lucky, that impulse results merely in distracting bits of ill-considered fan service, like when Dracula pops impossibly out of his coffin like Max Schreck’s Count Orlock just in order to supervise the gypsies packing his bags for the trip to England. (It’s a moment that belongs in What We Do in the Shadows— which did in fact turn the same trick into one of its signature sight gags.) More often and more seriously, it results in destructive lunacy like a Mina who can’t seem to make up her mind whether or not she really is the reincarnation of Princess Elizabeta, and a Dracula who is ultimately granted a redemption which he never seemed to want, and certainly never worked for. If you really want to make Bram Stoker’s Dracula, then you have to forget about Dan Curtis’s. You have to forget about F.W. Murnau’s, and Tod Browning’s, and Terrence Fisher’s, and John Badham’s. And you sure as hell can’t succumb to the temptation to make Secret Origins: Dracula, revealing that the count was a good guy all along, and that it’s really God who’s the big, old stupidhead. I mean, go ahead and make that movie if you want to, but don’t then come around telling me that it’s the most faithful adaptation ever. Not even if Quincy Morris is in it. And not even if Dracula has a moustache.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact