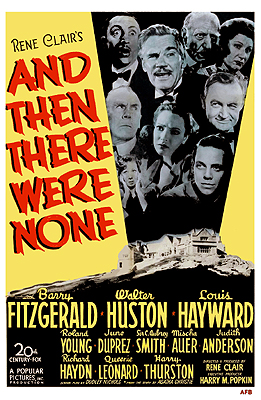

And Then There Were None / Ten Little Indians / Ten Little Niggers (1945) ***

And Then There Were None / Ten Little Indians / Ten Little Niggers (1945) ***

Agatha Christie’s 1939 novel, variously published as And Then There Were None, Ten Little Indians, and Ten Little Niggers (the latter in the UK, where they managed to out-racist the US for once), wasn’t the first body-count murder mystery. Indeed, it wasn’t even the first one to use the sometimes-eponymous nursery rhyme as an organizing framework for all the killing. It might justly be said, however, that Christie’s was the body-counter that every subsequent writer of the things had most in mind until Friday the 13th came along 41 years later. For that matter, Friday the 13th itself might be thought of And Then There Were None filtered through the “avenging the dead son” variant of the Cropsey legend. As you would expect for such an influential novel, And Then There Were None was filmed straight several times in addition to spawning more cinematic ripoffs than anyone could possibly count. The first movie version appeared in 1945, as part of a loose cycle of late-wartime mystery thrillers from 20th Century Fox. Like its stablemates, The Lodger and Hangover Square, the Fox And Then There Were None is a precociously dark and mean-spirited picture, with a closer tonal kinship to the gialli and slasher movies of later years than seems possible for a Hollywood production undertaken during World War II.

We begin with an amiably rude seaman (Harry Thurston) conveying eight sullen and seasick passengers to Indian Island, an out-of-the-way place dominated by a palatial manor house. None of them have ever met before, but they were all invited to a weekend get-together on the island by a certain Mr. U. N. Owen, whom none of them know either. (He could scarcely be U.N Owen if they were acquainted with him, right?) Lest we dismiss this whole crowd up front as a pack of dullards with no instinct for self-preservation, allow me to point out that each invitation was phrased so as to imply a plausible reason for Owen to extend it, and that each was delivered by some friend of the recipient. Strangely for a gathering arranged at the cost of such rigmarole, there are no other guests in evidence than the few who rode in on that boat, nor is the host himself anywhere to be seen. The only other people in the house are Thomas Rogers (Richard Haydn, from Young Frankenstein and Irwin Allen’s The Lost World) and his wife, Ethel (Queenie Leonard, of The Lodger and The Uninvited), who have been engaged for the weekend as servants for the party guests. Also, on the dinner table stands an ineffably ominous bit of decoration, a group of ten figurines (exactly as many as there are guests and servants) in the form of Native American warriors, of all things. No one likes the looks of this very much, except maybe Prince Nikita Starloff (Mischa Auer, from The Drums of Jeopardy and Sinister Hands), who makes a point of never refusing a chance to get good and tanked on somebody else’s vodka. The boat has already departed for the mainland, though, by the time all the causes for misgivings are apparent, and it won’t be coming back until Monday morning.

Owen’s guests are right to be uneasy, of course. Among the duties with which Rogers has been charged is to play a certain phonograph record at an appointed time on the first night. The disc turns out to contain a greeting from the gang’s mysterious host, but then goes on to accuse everyone present— even Mr. and Mrs. Rogers!— of murder. Some of these purported crimes are more direct than others. At the hands-on extreme, the Rogerses are supposed to have poisoned a former employer who had included them in his will for a substantial bequest by their modest standards. And at the opposite end of the spectrum, Emily Brent (Judith Anderson, from Rebecca and The Ghost of Sierra de Cobre) sent her nephew to live in a cruel orphanage rather than accept guardianship of him, and then washed her hands of the boy completely— a state of affairs which no doubt weighed heavily in his eventual suicide. The indictments against the others mostly fall somewhere in between. Starloff ran a couple over while driving recklessly and presumably intoxicated. Dr. Edward Armstrong (Walter Huston, from All that Money Can Buy and Kongo), by no means the prince’s inferior when it comes to drunkenness, botched a delicate operation while in his cups. Judge Francis Quincannon (Barry Fitzgerald) and private detective William Henry Bloor (Roland Young, of Sherlock Holmes and The Unholy Night) also stand accused of lethal professional malpractice; if Owen’s recording is to be believed, Quincannon once sentenced an innocent man to hang, while Bloor gave perjured testimony against a criminal defendant to similar effect. General Sir John Mandrake (C. Aubrey Smith, from The Phantom of Paris and The Witching Hour) sent the lieutenant with whom his wife was extramaritally dallying on a suicide mission. Philip Lombard (Louis Hayward, of Terror in the Wax Museum and The Son of Dr. Jekyll), another ex-soldier, oversaw the massacre of a native village while stationed in the East African colonies. And Vera Claythorne (June Duprez, from The Thief of Bagdad and The Brighton Strangler) is supposed to have killed her sister’s fiancé.

The guests’ reactions to hearing the charges against them are similarly varied. Most of them maintain fairly effective poker faces, neither admitting guilt nor protesting innocence. There are a few, however, who quickly declare themselves one way or the other. Vera, for instance, swears that she had nothing to do with killing the guy who never quite became her brother-in-law, and makes a reasonably convincing presentation of it. General Mandrake’s denials aren’t nearly as persuasive, couched as they are in the belligerent bluster of a troubled conscience. Ethel Rogers collapses into hysterics, howling to her aghast husband that she knew someone would find them out one of these days. Emily Brent is all “not my circus, not my monkeys,” which is only to be expected, I suppose. If she wouldn’t accept responsibility for her nephew’s life all those years ago, why should she accept responsibility for his death now? The most on-brand reaction is that of Prince Starloff. He blithely confesses, complains about having his driver’s license revoked, quaffs about half a pint of vodka in one big slug, and immediately drops dead. Cue mass panic and mutual recriminations.

The following morning, it turns out that Mrs. Rogers died too, apparently in her sleep. And in case there were anyone still considering accident or coincidence as part of their explanation for the two deaths, persons unknown have symbolically broken two of the Indian figurines from the dinner table centerpiece. The eight survivors sensibly spend the whole of that day thoroughly searching the house and its grounds for any sign of their homicidal host, but turn up absolutely nothing. Yet just the same, General Mandrake is stabbed in the back that afternoon, and a third ceramic Indian smashed. Obviously the killer remains on the island. Judge Quincannon, experienced as he is in interpreting criminal evidence, concludes that U. N. Owen must be concealing himself by posing as one of the guests. He takes a poll of his companions’ suspicions, and although it reveals nothing like consensus, the person with the most votes— Rogers— is made to sleep in the stable that night. You don’t even need me to tell you that he’s the next to die, do you?

Obviously a more proactive approach is called for, and two wary partnerships take shape in the interest of finding one. On one side are those sly, crooked old foxes, Quincannon, Armstrong, and Bloor, all of whom act like they’d rather be hunting witches than trying to expose a vigilante murderer. On the other are Vera and Philip, the last remaining guests who still claim not to have done what their host says they did. Their alliance is defensive not only against the unseen killer, but also against the three older men, all of whom profess to view their juniors’ insistence on their innocence as positive evidence of guilt— not only as regards their supposed past crimes, but of the current ones as well. And as for Emily Brent, above-it-all neutrality is a difficult and dangerous position to hold in a situation like this one.

Although And Then There Were None’s source novel is justifiably considered a genre classic today, it was looked at askance upon its release by critics who found it excessively cynical and misanthropic, and accused it of emphasizing carnage over crime-solving. This version of the story is less sour-tempered by exactly two characters’ worth, which on the face of it seems like a typical Hollywood adjustment. Don’t blame 20th Century Fox, though. The change originated in the stage play, which was the proximate basis for Dudley Nichols’s script for the film version. Agatha Christie wrote that play herself, evidently having decided somewhere along the line that the critics had a point, and that some of the rougher bits could use a little sanding down for the West End. Just the same, the movie remains impressive for its darkness and bleakness. 80% of the dramatis personae are nasty pieces of work, and the jury remains out on the other 20% until the final reel. Note, too, that that’s the case even though several of the characters are people in positions of significant public trust: a judge, a general, a soldier, a doctor, a detective. And Then There Were None is also unusual in its time for carrying over the novel’s relative disdain for detection. There’s no Miss Marple or Hercule Poirot here, but just a bunch of scared people trying to stay alive through the weekend. Indeed, the group that makes the biggest show of trying to get to the bottom of the mystery consists entirely of the likeliest-seeming suspects! To be sure, I was drawn to And Then There Were None precisely because of its important place in the prehistory of the slasher movie, but the last thing I expected was to be reminded so strongly of Twitch of the Death Nerve.

And Then There Were None is remarkable as well for its visual artistry, at a time when much of the American film industry seemed eager to shed that as completely as possible. No doubt the first place we should look to account for that is the overseas origin of its director, the French-born Rene Clair. Significantly, Clair’s career stretched back into the silent era, when visual artistry was virtually all that a filmmaker had at his disposal. His resumé is dotted throughout with intriguing titles, too. Alongside And Then There Were None, his best-known movies are probably The Ghost Goes West and I Married a Witch, two of the fantasy comedies that were so popular from the mid-30’s through the turn of the 50’s. Before that, back in the 20’s, Clair wrote and directed (in addition to some truly peculiar-sounding short films) The Phantom of the Moulin Rouge and The Imaginary Voyage. The former is another fantasy comedy featuring mad-science soul-extraction and a surprisingly high-stakes third act conflict. The latter concerns an office worker who seeks escape from the humdrum routine of his life in an underground fairyland of the imagination. And later on, after the end of World War II made it safe to return to France, Clair made a version of Faust called Beauty and the Devil. Although there’s nothing unreal or supernatural about And Then There Were None, Clair nevertheless brought to it the eye of a habitual fantasist. The mansion on Indian Island is spooky and foreboding despite looking credibly lived-in, and the isolation of the setting is palpable throughout. Clair got away with some surprisingly gruesome murders, too, apparently by the simple expedient of limiting himself to showing their aftermaths. (I’ve never been able to understand how that works, but it’s a remarkably reliable trick. Even in the 80’s, it was amazing what the censors would allow, provided that a director could wait until the wet work was complete before training the camera on its results.) Watching And Then There Were None, it’s easy to imagine that we’re witnessing the making of a haunted house, that Indian Island is going to be shunned for a century once word gets out of the doings there this weekend. The most impressive display of Clair’s ability, though, occurs in And Then There Were None’s very first scene. With barely a word of dialogue, the opening pans up and down the sides of the boat tell us enough about all eight people to let us begin forming opinions of their individual merits and personalities. We can guess which of the guests are timid, which ones are self-centered, which ones are easygoing, and which ones are prigs. And although the movie is well laden with attempts at misdirection and legerdemain regarding the exact scope and nature of each character’s corruption, nothing that Clair shows us later is ever in contradiction to those impressions. Plainly I owe it to myself to seek out more of this director’s work going forward.

Can you believe the B-Masters Cabal turns 20 this year? I sure don't think any of us can! Given the sheer unlikelihood of this event, we've decided to commemorate it with an entire year's worth of review roundtables— four in all. These are going to be a little different from our usual roundtables, however, because the thing we'll be celebrating is us. That is, we'll each be concentrating on the kind of coverage that's kept all of you coming back to our respective sites for all this time— and while we're at it, we'll be making a point of reviewing some films that we each would have thought we'd have gotten to a long time ago, had you asked us when we first started. This review belongs to the second roundtable, in which we each focus on those odd, dusty corners of the cinematic universe that have become our particular fixations. For me, that means the prehistory of the slasher film, 70's fadsploitation, the works of local antihero John Waters, and movies touching on musically-oriented countercultures, punk rock especially. Click the banner below to peruse the Cabal's combined offerings:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact