Sherlock Holmes (1922) **

Sherlock Holmes (1922) **

Apparently some things really don’t ever change— or at least they change at such a glacial pace that you’re apt to miss it without very sophisticated measuring equipment. Think about all the things you might expect present-day Hollywood to get wrong in a Sherlock Holmes movie. Perhaps the writers would give Holmes a love interest; have him do more fighting and shooting than detecting; make Professor Moriarty an intimate, lifelong enemy instead of just one unusually formidable opponent among many. They might waste fully a third of the film on a totally unnecessary origin story, maybe even finding a way to make Moriarty the reason Holmes got into the crime-solving business in the first place. If they really wanted to fuck it up, they could treat the whole movie as an adventure story rather than a mystery, serving up a busy succession of capers and counter-capers with no real focus or narrative through-line. The producers might assemble a capable cast, with a deservedly big star and some reliable character actors, then leave them at the mercy of a director with no affinity for the material and little idea of what to do with all the thespian prowess at his disposal. And if there were a love interest involved, they might fill the part with some no-talent tart whom somebody with a vested interest in her career was pushing as the next big thing despite the inescapable charisma vacuum that opened up every time she stepped in front of a camera. All in all, we could plausibly expect to get a nice-looking but totally empty popcorn flick that we would begin forgetting about the second the credits started to roll. And that very well might be what Hollywood gave us last year, with Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes— I wouldn’t know, as I haven’t bothered to see it yet. What I do know is that the above description exactly fits Goldwyn Pictures’ Sherlock Holmes from 1922. Like I said, apparently some things really don’t ever change.

Actually, it might have made more sense for Goldwyn to entitle this movie Moriarty; heaven knows the professor gets at least as much screen time as Holmes, and he makes a far stronger impression as a character. This Moriarty is played by Gustav von Seyffertitz (of The Bells and The Bat Whispers), made up to look remarkably like the Crypt Keeper as he originally appeared in the old E.C. comics of the early 50’s. Sherlock Holmes never comes right out and says this, but it strongly implies that Moriarty is somehow implicated in literally every crime committed in the British Isles. For example, somebody has made off with Cambridge University’s athletic fund, and suspicion has fallen hardest on Prince Alexis (Reginald Denny, from Rebecca and Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror), youngest of the three sons of Count von Stalburg (David Torrence, from The Mask of Fu Manchu and the silent The Drums of Jeopardy), lord of the Germanic principality of Arenberg. Alexis swears he’s innocent of any wrongdoing; however, his valet, Otto (Robert Fischer), is one of Moriarty’s agents. Does this mean that the world’s greatest criminal genius has stooped to stealing the jockstraps off of England’s college cricket-players? Very possibly. I’m honestly not sure, though, because all the schemes employed here by Moriarty and his subordinates are as counterproductively convoluted as anything Daddy Foxx tried in The Monkey Hustle. What I can tell you is that the theft was directly perpetrated by another student named Forman Wells (William Powell), that Forman was put up to it by Moriarty through his top lieutenant, Bassick (Robert Schable), and that framing the prince seems to have been a bigger object than whatever money the athletic fund contained. But if there was ever a recognizable purpose to the frame-up itself, it must have been discussed in one of the bits of footage that still haven’t been located. (Sherlock Holmes was believed lost until 1970, when representatives of the George Eastman House uncovered a mass of unedited negative accounting for most of the picture— together with mountains of unused takes and who knows what other celluloid flotsam. Film historian Kevin Brownlow spent ages putting the movie back together again, aided initially by director Albert Parker, who remarkably was still alive when the project first got underway. A second restoration was undertaken in 2001, incorporating newly discovered footage, but even that version— the one on which this review is based— doesn’t quite reflect what first-run audiences would have seen.)

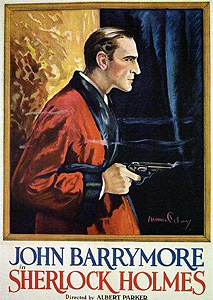

In any case, Alexis is at his wits’ end, and he confides in an upperclassman by the name of Watson (And Then There Were None’s Roland Young, much less irritating than he was in The Unholy Night by virtue of having no audible dialogue). Watson has a curious suggestion for the prince. Evidently, one of Watson’s classmates is a sort of eccentric genius with a peculiar talent for getting to the bottom of a mystery. The lad’s name is Sherlock Holmes (John Barrymore, later of Svengali and The Mad Genius), and Watson is quite confident that he will be able to figure out who is trying to incriminate Prince Alexis and why.

This is a strangely distractible Holmes we have here. Although I gather that Barrymore’s characterization was intended to communicate that nothing, no matter how seemingly insignificant, escapes his notice, what it really looks like is some unholy intersection of attention deficit and obsessive-compulsive disorders, as every detail of Holmes’s surroundings seizes his undivided attention successively. That includes Alice Faulkner (Carol Dempster, from One Exciting Night and The Sorrows of Satan), by the way, whom Watson identifies as the sister of Prince Alexis’s fiancee, Rose (Peggy Bayfield). Yes, this would be that love interest I mentioned earlier, and the no-talent tart as well. Dempster was D. W. Griffith’s girlfriend, to which status she owed her frequent and otherwise inexplicable casting as the female lead in in the films he made during the last decade of his career. Evidently Parker or his producers hoodwinked themselves into believing that quantity implied quality, and gave Dempster one of her only two known screen acting gigs under the direction of someone other than Griffith. Barrymore has better chemistry with his calabash pipe, and Holmes’s concluding announcement that he and Alice are to be married comes as by far the biggest shock in the whole film.

Be that as it may, Holmes swiftly fingers Wells as the culprit in the athletic fund case, and Otto gets sufficiently worried to mention Holmes and his investigation to Moriarty. The professor summons Wells to his secret headquarters in Limehouse for an accounting, and it is on the way there that Holmes falls upon his prey, hitching a ride in Forman’s cab. Wells confesses everything, dropping the dime on Moriarty while he’s at it, and Holmes is so fascinated by his description of a criminal so slippery as to be invulnerable even to the vaunted Scotland Yard that he contrives to go to Limehouse in the hapless thief’s place. The ensuing introductory meeting between the future arch-nemeses makes precious little sense in light of either participant’s supposed character, but the result is that Holmes leaves the professor’s lair having found his mission in life. He’s going to see Moriarty brought to justice if it takes him a hundred years!

Somewhat surprisingly, we’re not quite finished with Alexis von Stalburg yet. Not long after the athletic fund caper is put to bed, the count comes to Alexis bearing bad news. Both his elder brothers were killed in a car wreck, leaving him Crown Prince of Arenberg. That makes his personal life a matter of dynastic politics, which means in turn that Rose Faulkner has got to go. Yes, yes— the count knows she’s already in Switzerland, waiting for the college term to end so that she and Alexis can tie the knot and commence their honeymoon, but this sort of thing is an unavoidable occupational hazard of being among the crowned heads of Europe. A monarch can’t marry just anybody, and Rose… well, she’s pretty much just anybody. Alexis isn’t happy about it, but he understands his father’s point. The wedding is called off, the prince returns to Arenberg, and Rose becomes so distraught that she pitches herself off of a mountaintop while on a hiking tour in the Alps. Sherlock Holmes takes the latter news badly when it reaches him (“Prince Alexis is a blackguard! He bears the moral responsibility for that poor girl’s death!”), but I’m inclined to say that’s his mostly invisible affection for the other Faulkner girl talking.

Years pass, although nobody seems to get any older. Holmes and Watson graduate from Cambridge, and the former takes up residence at 221 Baker Street with a reformed Forman Wells as his valet. Watson marries, and goes into medical practice. Holmes begins making a name for himself as a “consulting detective,” his activities driving Professor Moriarty ever deeper into seclusion (or so we are told by both an intertitle and the villain himself, although we certainly never see it). And we in the audience still can’t find much indication of anything like a plot at work in this movie. Eventually (and I do mean eventually), Alice Faulkner resurfaces with a cache of letters to and from Rose, unmistakably linking her sister’s suicide to the termination of her engagement to Prince Alexis. Alice means to make the contents of this correspondence public with the aim of embarrassing the prince and gaining thereby some measure of vengeance, but Moriarty is of the opinion that she’s thinking small when he learns of Alice’s plans (however the hell that happens…); revenge has its appeal, of course, but extortion is so much more profitable! The professor has Bassick kidnap the Faulkner girl, placing her in the custody of crooked financier James Larrabee (Anders Randolf, from the last silent version of Seven Keys to Baldpate) and his wife, Madge (Hedda Hopper, of Dracula’s Daughter and One Frightened Night). Then he sets about blackmailing Alexis with the letters. Naturally, Alexis runs straight to Sherlock Holmes, but the detective refuses at first to take his case. To be perfectly frank, Holmes thinks Alexis is getting exactly what he deserves. He changes his tune, though, when Alexis mentions Moriarty, and explains that Alice is effectively his prisoner. The woman Holmes has loved from afar since his senior year of college in the clutches of his sworn enemy? Not if Holmes has anything to say about it! And with that, the game— at very, very long last— is something at least faintly resembling afoot.

Sherlock Holmes has little to do with anything written by Arthur Conan Doyle. Instead, it derives from a stage play of the same name written by William Gillette in 1899. Gillette, an actor as well as a writer and producer, cast himself in the title role when his Sherlock Holmes debuted in November of that year, and so popular was the play that he would perform it more than 1300 times over the ensuing two decades. He was thus the first “definitive” Sherlock Holmes, albeit one whom we are unable to evaluate beside his numerous successors. Gillette did assay the role on film once, in 1916, but that earliest feature-length American Holmes picture remains stubbornly among the lost.

If the 1916 version of Sherlock Holmes ever does turn up, it’ll be hard pressed to come as a bigger let-down than this remake. I’d read that John Barrymore was never very comfortable as a motion-picture actor, but it always seemed hard to credit that given the caliber of his performances in those films of his that I’d seen. After Sherlock Holmes, though, I think I’m starting to get it. Barrymore honestly doesn’t seem to have much of a handle on what he’s doing here, alternating between a battery of bizarrely exaggerated behavioral affectations and almost total immobility. Only in a couple of scenes do we see anything like the performance that the phrase, “John Barrymore as Sherlock Holmes,” would tend to conjure up in the minds of silent movie fans, with the result that Holmes gets totally overshadowed by Gustav von Seyffertitz’s Moriarty. Meanwhile, one might argue that even if Barrymore had brought his A-game, this still wouldn’t be the Barrymore-as-Holmes of our imagining, because the character is written so far from the mark. The most glaring example can be seen in a line of dialogue shortly before Holmes springs his trap on Forman Wells: “It is easier to know that Wells did it than to tell you how I know.” Sorry, but no. Sherlock Holmes does not get uncanny hunches. His methodology is observation and logic raised to the level of super-power. He’d have no trouble telling you exactly how he knew, and he’s such an incorrigible showoff that he’d be unable to resist doing so the moment the subject came up. There’s defensible reinterpretation, and then there’s just plain getting it wrong; this is just plain getting it wrong.

The misconceived characterization and sprawling, incoherent storyline are rendered doubly irritating because there’s so much about Sherlock Holmes that is superficially good. This is a handsome and nicely atmospheric movie throughout, and a few of its set-pieces are quite strong when taken in isolation. The scene-setting aerial tracking shot over London that opens the film may not look like much at first glance, but when you remember that this was 1922, it becomes very impressive indeed. Moriarty’s introductory scene is a corker, too, although it really feels more like Sax Rohmer than Arthur Conan Doyle. Finally, there’s the showdown between Holmes and Moriarty at the climax. It gets a little goofy at the very end (for a guy who keeps torture racks in his office, Moriarty is an awfully good sport about being caught), but the sequence in which the two antagonists stalk each other from room to room through Dr. Watson’s house is a fine example of the sort of visual artistry that temporarily all but vanished from the movies after the talkies took over. If just that scene had survived, a person would be justified in assuming that Sherlock Holmes was a lost work of genius. But as it happens, we’ve got more than enough of the movie now to know better.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact