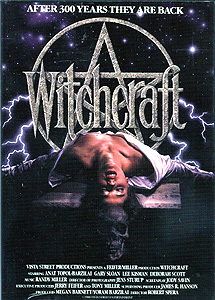

Witchcraft (1988) -½

Witchcraft (1988) -½

This is what you call being in the right place at the right time. A dull, disjointed Rosemary’s Baby rip-off featuring a thoroughly untalented cast, shot on video by people so inept and inattentive to detail that the second of the two copyright notices on the old VHS prints gives the release date as 1188 (need another “M” in there, kids), Witchcraft would seem to have nothing whatsoever going for it. But just as it arrived on the scene, the direct-to-video market was poised to become the primary venue for low-budget filmmaking, and a voracious demand for product, no matter how poor the quality, was about to open up. Meanwhile, the in-name-only sequel was fast becoming a major phenomenon, turning any genre film with a sufficiently memorable title into a potential franchise by eliminating those pesky traditional requirements for things like recurring characters or some minimal semblance of inter-episode continuity. Finally, and of the greatest importance, during the decade which began shortly after Witchcraft’s release, the makers and distributors of direct-to-video horror movies lost all sense of proportion or perspective, coming to the conclusion that since any memorably-titled genre flick could now become a long-running franchise, then every such movie should spawn a series of ever-cheaper sequels. As a result, by 2002, there were no fewer than twelve Witchcraft movies. That means more sequels than Hellraiser, The Howling, A Nightmare on Elm Street, or even Friday the 13th. Hell, that’s as many movies as there are in the Halloween series and the Texas Chainsaw Massacre series combined! And all for a crummy little reincarnated witches flick that nobody in the world ever gave two shits about in the first place.

One night in what we will later learn to be 1687, a man and a woman who will later be identified as John and Elizabeth Stockton are dragged from their home and burned at the stake by a leering mob of their neighbors. Elizabeth is pregnant, and since the scene keeps cutting ahead to the modern-day delivery room where Grace Churchill (Anat Topal-Barzilai) is giving birth, I’m thinking that’s an extremely significant detail. It might also be worth noting that Grace’s husband (Edward Ross Newton, also known as Gary Sloan) is named John. Omens aside, the baby comes out apparently normal, and all seems to be well— or at least, everything except the fact that Grace’s best friend, Linda Swanson (Deborah Scott), doesn’t get to see little William even after a truly disheartening comic-relief effort to sneak past the hospital staff and gain entry to Grace’s room.

Now that I think about it, it might also qualify as something not being well when John reveals his plans for his wife’s immediate future. John’s got a busy week at work coming up, and with Grace still recovering from the ravages of birthing, that would normally mean that no one would be in much of a position to look after the baby. Thus John has made arrangements with his mother, Elizabeth (Mary Shelley— really, that’s what it says in the credits), for the three of them to stay for a while at her place. Mom’s place turns out to be a rather rundown and atrociously ugly mansion which has apparently been in the family for something like 300 years, and I can kind of understand why both it and its owner give Grace the creeps— I mean, mildew and discoloration aside, the Churchill mansion displays a certain architectural kinship to the Amityville Horror house (revealing thereby that it can’t possibly be as old as the script would have it, incidentally), and Elizabeth Churchill projects a species of smarmy solicitousness that is generally the sole province of villains in stories for children. Consequently, we join Grace in looking askance at her mother-in-law when she tries repeatedly to horn in on the younger woman’s parenting decisions, brews vile-tasting tea for her to drink before bedtime, and goes out of her way to spend more time holding the baby than anyone else. We will not be surprised when, on her first night in the mansion, Grace has a nightmare in which Elizabeth and a man in a black cloak (he keeps his back turned to the camera, but any fool can tell it’s John wearing that dollar-store Dracula cape) perform some kind of Satanic sacrificial ceremony in the overgrown backyard. Nor will we be surprised the next morning when the camera (but not Grace) notices evidence that the nocturnal blood ritual really did occur.

A bit later, Grace gets in touch with her old priest, Father James (Alexander Kirkwood), and invites him over to baptize William. He and Linda come by separately on the same afternoon, when the house is already filled with creepy, socially stunted old people who are presumably members of John’s side of the family. The kid doesn’t get his baptism, though, because the moment James lays eyes on him, he has a vision of a raging, hellish fire in the living room, and is overcome by a wave of nausea. Then, in the bathroom mirror, the priest is confronted by scenes from the execution of the Stockton couple. James excuses himself on grounds of illness, and rushes back to his church after giving Grace his rosary and getting from her a promise to bring William over for his baptism the next day.

Now we can all see what’s going on here, right? The Churchill family are somehow descended from the long-dead Stocktons, and William is the reincarnation of Elizabeth Stockton’s unborn baby, which probably makes the kid the Antichrist as well. Otherwise, why would this clan of devil-worshipers be making such a big deal over him? The trouble is that screenwriter Jody Savan and director Robert Spera are hell-bent on pretending that we haven’t figured out a goddamned thing, and thus they do everything in their power to make us believe that Grace wouldn’t figure out a goddamned thing, either. Father James obviously knows something, but before he can get word to Grace, or give William his baptism either, the priest comes down with some sort of supernatural lumpy-face disease and then hangs himself from a tree in the Churchills’ backyard for no fucking reason. Grace keeps snooping around in the wing of the house where nobody’s supposed to go (“We don’t use this part of the house— it really isn’t safe”), but even after she finds both an evil mirror that shows her “horrifying” visions (but different horrifying visions from the ones she describes to Linda, I hasten to emphasize) and an antique painting depicting her husband’s heretical ancestors, she still can’t seem to put the pieces together. Only when John reveals that the house where they had been living before has burned down during their stay with Elizabeth, and a trip to the charred and crumbling ruins turns up the information that it did so much more recently than her husband would have her believe, does Grace seem to get it through her head that there really is something seriously wrong with something other than her own mind. And only when Linda is decapitated by persons unknown while helping Grace explore the forbidden wing of the mansion— an hour and nineteen minutes into a 95-minute movie!— does Witchcraft begin moving toward its all-too-obvious conclusion in any remotely decisive manner. Then, after all that, it never does bother to address what ought to have been the main point of the story, the presumably diabolical nature of Baby William.

When attempting to make a moody psychological horror film, there are three things which one simply cannot do without: mood, psychology, and horror. Witchcraft fails utterly on all counts. Despite the visually compelling setting provided by the Stockton/Churchill mansion, the film never develops the slightest hint of atmosphere, largely because the cost-conscious decision to shoot on videotape and score with a low-end synthesizer gives Witchcraft the look and feel of a small-business employee orientation video. Obviously, Robert Spera was at the mercy of his budget, but even in 1988, there were things you could do with lighting and post-production processing to minimize the detrimental effects of video cinematography. Meanwhile, if you lack the funding for anything but an electronic score, then for God’s sake, suck it up and have an electronic score. It worked for Lucio Fulci, it worked for Dario Argento, and if your composer has any idea what he’s doing, it’ll work for you, too. Don’t try to trick me into thinking you’ve got an orchestra when all you have is one guy with a Casio, because it isn’t going to fly!

Beyond the shortcomings of atmosphere, Witchcraft also shows that its creators had very little understanding of how psychological horror works. While I’m willing to give them a smidgen of credit for attempting to take the high road with a character-driven story that was supposed to hinge on the question of whether or not the central figure is merely going insane, I must simultaneously condemn them for attempting to drive that story with characters who are nothing more than stock types, whose motivations are apparent solely because I’ve seen so many other, better films in which people in similar situations behaved the same way, and for making it obvious from the get-go that Grace’s troubles are hardly figments of her imagination. When Elizabeth’s menacing, mute butler (Lee Kissman) comes to Grace’s rescue in the final scene, for example, there’s no honest reason for him to do so; there has been virtually no interaction between the two of them up to then and certainly nothing that could be taken to offer any insight into Ellsworth’s feelings regarding his mistress, her hapless would-be victim, or his role in the Stockton/Churchill family’s ongoing Satanic conspiracy. All we get by way of explanation is a throwaway scene relatively early on, when, for absolutely no discernable reason, Grace brings Ellsworth a rather mangy-looking white carnation from the garden. But because similar small kindnesses have been warming the hearts of evil henchmen since at least the days of Jungle Captive and The Raven, we’re supposed to accept without comment that Ellsworth would want Grace to give him a common and unattractive flower, and would attach enough deeper meaning to the gesture to betray his benefactors for Grace’s sake during the final reel. Even more astonishing is the total absence of direct justification for John and Elizabeth’s occult interest in William. I’m assuming he’s the Antichrist, because John and Elizabeth Churchill are eventually revealed to be the reincarnations of John and Elizabeth Stockton (a revelation which blandly ignores the beautifully sick implications of a husband and wife being reborn as mother and son), and because everybody in the Churchill family behaves exactly like the coven of geriatric Satanists in Rosemary’s Baby, but the fact is that I really have no reason to believe that on the basis of anything that happens in Witchcraft itself.

Finally, and most damningly, Witchcraft is utterly devoid of any but the most flagrantly ersatz horror or suspense. The movie is chock full of prowling POV-style camerawork which turns out to represent the first-person perspective of nobody but the cameraman himself. “Spooky” music plays at the most inappropriate of moments, as if the “they’re coming to get you” cue were set up on a timer to be triggered every eight minutes, regardless of the requirements of the scene. The tiresomely rare scare scenes are pathetic in the extreme: William’s crib surrounded by post-production flames? Not scary. Clips from earlier in the movie appearing in the bathroom mirror? Not scary. Extreme closeup on Elizabeth chewing rare roast beef? Not remotely scary. Even the two biggies are more laughable than anything else— Linda’s decapitation because it requires such a transparently obvious plot contrivance to set it up, and the hanging of Father James because it serves no function except to draw attention to the wretchedness of Witchcraft by reminding the audience that it was legitimately shocking when the nanny hung herself in The Omen and that it had some kind of impact on the story when the priest was laid low in The Amityville Horror. Spera and Savan’s efforts at suspense are feebler still— if you’re going to treat the plot against the heroine like some big-ass mystery, then it behooves you not to give everything away within the first fifteen minutes. Someone might also have tried to impress upon producer Yoram Barzilai the importance of not promoting Witchcraft with a tag-line like “After 300 years in the Womb of Hell, the Son of Satan is born!” A thing like that kind of tips the movie’s hand, you know?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact