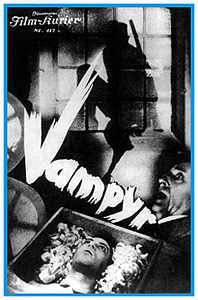

Vampyr / The Vampire / Castle of Doom / Not Against the Flesh / The Strange Adventure of David Gray / Vampyr: Der Traum des Allan Grey / LíEtrange Aventure de David Gray (1932) ***Ĺ

Vampyr / The Vampire / Castle of Doom / Not Against the Flesh / The Strange Adventure of David Gray / Vampyr: Der Traum des Allan Grey / LíEtrange Aventure de David Gray (1932) ***Ĺ

The early 1920ís may have been the heyday of German expressionism, but evidently it was still clinging to life (or maybe unlife?) a few years into the 1930ís. Vampyr/The Vampire/etc., a Franco-German film that was Danish director Carl Dreyerís first foray into the realm of talking pictures, isnít usually classed with the likes of The Golem and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but take a close look and youíll see that itís hard to find a label that fits it better. And despite its age, it is also one of the most eerily disorienting movies Iíve seen in my many years as an avid fan of fright films.

When young David Gray (Allan Grey in the German versionó either way, heís played by Julian West, who fronted the money for Vampyr under his real name, Baron Nicholas de Gunzberg) arrives in the small French village of Courtempierre, he sees almost immediately that it isnít like other towns. The whole place seems nearly deserted, and all of the people he does meet are somehow threateningly odd. Thereís the old man with the disfigured face who lives in the attic of the inn where Gray is staying, who simply looks at David accusingly when he wanders into his room accidentally. There are the young girls who always seem to be skulking about at the limits of Davidís field of vision, who ignore him completely when he tries to get their attention. But most importantly, thereís the middle-aged man David encounters in the innís parlor (Maurice Shutz, from the 1932 version of Fantomas), who looks him straight in the eye and tells him, ďShe must not die,Ē before handing him a small parcel on which he has written, ďTo be opened after my death.Ē

Itís a damn creepy way to start a vacation (or a business trip, or whateveró no reason for Davidís coming to Courtempierre is ever given), but thereís even worse to come. Gray spends the rest of the afternoon walking around the village, and the sights get stranger by the hour. At one point, David finds himself following the shadow of an armed man with an artificial leg (he canít see the man casting the shadow) until it becomes obvious that the shadow has been prowling the streets without its owner! (The shot in which the shadow walks up to a one-legged soldier sitting on a bench, and then assumes its proper place on the wall behind him is one of the creepiest pieces of trick cinematography Iíve ever seen.) Fleeing from the scene of this nightmarish vision, Gray winds up outside what seems at first to be an abandoned building beside a cemetery, but soon the muffled sounds of barking dogs and children at play pique Davidís curiosity, and he goes inside to have a look around. All he finds within, however, is a grizzled old man who bears a somewhat comical resemblance to Mark Twain (Jan Hieronimko). When asked, this man insists that there are neither dogs nor children anywhere about, and shoos David away from the place. The old man then waits for David to leave, and goes upstairs to talk to a dour old woman in expensive-looking clothes (Henriette Gerard).

After leaving the building by the cemetery, David again sees disembodied shadows, and again he follows them, this time to a grand old chateau on a heavily wooded lot. The house turns out to belong to the man who gave him the package that morning; he lives there with his two teenage daughters, Leone (Sybille Schimtz, from the 1934 German version of Master of the World) and Gisele (Rena Mandel), and a small staff of servants. David is invited in when he is noticed on the grounds of the chateau, and while talking with his host, he learns that Leone, the older of the two girls, is deathly ill with a strange ailment. But before the master of the house can go into any detail, that one-legged soldier from the village snipes him through the window, and then disappears. The wounded man dies just moments later.

Well, at least this means David can open that package, doesnít it? It proves to contain an old, leather-bound book aboutó you guessed itó vampires (note the plot device lifted from Murnauís Nosferatu). David dutifully begins reading the book, which, or so we are told, concerns a subject that was already of some interest to him, and his studies have the usual effect. That is to say, he soon begins to notice eerie parallels between what he reads and what he sees going on around him. For example, the servant who went to summon the police after his master was shot returns dead, with his throat slit; one suspects he never even reached his destination. Then thereís the vanishing sniper; the book says vampires often press the ghosts of executed murderers into service to do their dirty work by day. And of greater significance, Leoneís mysterious illness starts to look more and more like the work of a vampire. As her condition worsens, she begins to talk alarmingly of damnation, and to watch her sister and servants with a hungry gaze after the sun goes down. Eventually, the head servant (Albert Bras) summons a doctor to have a look at the girl. Damned if it isnít Mark Twain! The doctor points out the small wounds on Leoneís throató like a rat bite, he saysó and tells David that Leone has lost much blood, and will require a transfusion. Gray himself volunteers to donate his blood, and perhaps it is the weakness that comes over him as a side-effect of the operation that explains what happens next.

That night, when he sits down in the graveyard next-door to the chateau to ponder everything he has seen in Courtempierre, David hasó what? A dream? An out-of-body experience? Itís difficult to say. But whatever it is, it takes him back to that building by the cemetery, which now looks to be the undertakerís workshop. Again, he finds the doctor there, but this time, Gisele is with him, and she is tied to a chair in the workshopís back room. Then David happens to notice the coffin being prepared for burialó itís his own, and heís already lying inside it! David watches helplessly as his body is sealed up in the casket, and then carried off into the cemetery. But before the pall-bearers reach the gravesite, David sees himself sitting safely on the same bench in the cemetery where he fell asleep earlier. He rushes over to climb back inside himself, and awakens most relieved.

But it canít have been a mere dream, because Gisele is missing from the chateau when he returns, and Leone is even sicker than she was before. And while David was out, the butler happened upon the book his master gave the young visitor, and had a chance to read much of it. In particular, the chapters he perused told of an outbreak of vampirism in Courtempierre many years ago, which was eventually traced to a cruel old woman named Marguerite Chopin, who had died not long before. The butler gets it in his head that Marguerite may be responsible for Leoneís affliction, and the next morning, he takes it upon himself to open the womanís crypt and deal with her in the manner the book prescribes for the undead. This happens just as David is returning from his strange, strange night in the cemetery, and he joins in to help the butler with his grisly task. And wouldnít you know it, Marguerite Chopin turns out to be the woman with whom we saw the doctor hanging out the first time David went to the funeral parlor. Sheís in perfect shape despite the many long years sheís supposedly been in the ground, but when David and the butler finish driving the iron spike through her heart (looks like The Return of the Vampire wasnít the first movie to use this method after all), she immediately shrivels up to little more than a skeleton.

Okay, so thatís all well and good, but weíve still got the doctor to deal with, and if Davidís dream is any indication, weíve got Gisele to rescue as well. Fortunately, David has the butler to help him with these duties, and both are accomplished without much delay. I wonít say just what happens, but Iím quite sure Iíve never seen a villain get whatís coming to him like this before...

I warn you: if you decide to watch Vampyr for yourself, youíre going to spend most of the hour and a half that it will take you in a state of extreme confusion. This movie has had a tremendous influence on European horror cinema, and a big part of that influence has to do with the secondary status to which Dreyer assigns his story. (Another part of it has to do with the inordinate fondness of European horror directors for glass-topped coffins, but thatís another matter altogether.) Itís not that he doesnít care about the plot (that wouldnít be invented for a while yet), but it very definitely takes a back seat to the disorienting atmosphere and nightmarish imagery, which, given Dreyerís deft touch with such things, is really a point in this movieís favor. These qualities are further heightened by the fact that Vampyr is handled very much like a silent film, with almost no dialogue and many of the more complicated plot points addressed by way of intertitles, usually in the guise of pages from Davidís book of vampire lore. This eccentricity is surely partly explained by the odd way in which Dreyer made the movie. It was shot silent on location in France, and then overdubbed at the Klangfilm studio back in Germany. (Note that, though the dialogue is in German, everything any of the characters writes is in Dreyerís native Danish.) The total effect is to make Vampyr very difficult to follow until about the two-thirds mark, when all (well, most anyway) of the pieces begin coming together. But unless youíre easily bored, youíll be too busy just looking at Vampyr to worry much about where the story is or is not going for much of that first baffling hour.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact