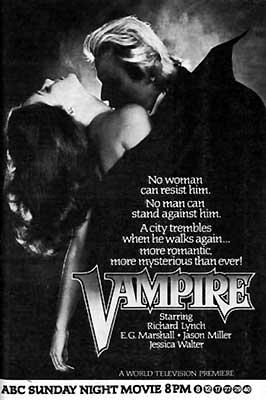

Vampire (1979) ***

Vampire (1979) ***

As we’ve discussed before, a lot of the made-for-TV movies of the 1970’s were originally produced as pilot episodes for weekly series that died aborning. It’s usually easy enough to spot these (cast members credited as “guest stars” are one obvious tell, as are lead performers with more small-screen than big-screen appearances on their resumés), and it’s similarly easy in most cases to sort out what a typical regular episode would have been like had the network bought what the creators were sellling. After all, the latter is the whole point of a pilot episode, right? Vampire is an intriguing exception to that rule, however. Looking at it in reference to what else was on the boob tube in 1979, I can imagine three totally different directions for the series that never was, and although they don’t all seem equally likely, they’re all plausible enough that I have little idea which of them (if any!) writer/producer Steven Bochco and co-writer Michael Kozoll might really have had in mind.

To begin with, simply because Vampire was a horror pilot, we ought to consider the possibility that the series would have ended up being an anthology, so that the only things to carry over from the initial episode would be the tone, sensibility, and general subject matter. This would have been the safest, most conservative thing to do from a business point of view. Until “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” came along, the only really successful non-anthology horror program on television was “Dark Shadows,” and there’s a strong case to be made that the increasingly bizarre saga of the Collins clan owed its success very specifically to the show’s positioning as a mutant daily soap opera. The series that Vampire was intended to launch obviously wouldn’t have had that advantage. Nevertheless, it seems pretty clear that Vampire is setting up some kind of continuing future for its characters, and one doesn’t normally do that unless the plan is for most of them to return in the episodes to come.

The second possible direction that I can envision for “Vampire: The Series” is something like a more serious riff on “Kolchak: The Night Stalker”— or alternately, a San Francisco-based precursor to “Angel” with more smoking and uglier clothes. In this conception, I foresee the pilot movie’s co-protagonists, having survived their first encounter with supernatural evil, going into business as paranormal private eyes, on the theory that they can’t be the only people in town to have trouble with ghoulies, ghosties, long-leggedy beasties, and things that go bump in the night. Heaven knows television in the 70’s and 80’s was hopelessly addicted to shows about people who specialized in solving crimes too weird in one way or another for the conventional authorities! The obvious counterargument here, though, is that “Kolchak” flopped hard, even despite the high regard in which the two telefilms that begat it were held, getting shitcanned after just half a season. By most accounts, the show’s insurmountable problem was that TV audiences of the 70’s were unable to accept the same one guy in the same one city constantly bumping into one monster after another, week after week after week. That doesn’t seem like a mistake that any producer as savvy as the creator of “Hill Street Blues” would be eager to make anew, even if the premise sounds like a surefire hit from the perspective of the 21st century.

And so we’re left with the third, and to me most credible, possibility: What if Bochco and Kozoll were trying to develop the weirdest “Fugitive” knockoff yet? I should probably take a quick detour at this point, for the benefit of my readers who aren’t TV antiquarians. “The Fugitive,” which aired on ABC affiliates from the fall of 1963 through the spring of 1967, was one of those “wandering loner” shows that were so popular before the 1990’s taught American television audiences to expect ongoing storylines and inter-episode continuity. (There’s a bit of irony there, because “The Fugitive” was also the first US TV series ever to wind up its run with a proper, premise-resolving series finale.) It followed the travels and travails of a doctor on the run from the law after being falsely convicted of murdering his wife as he scoured the country for the true culprit, a mysterious one-armed man. So big a hit was “The Fugitive” that riffs on its format continued to appear from time to time even 30 years after it went off the air— and curiously enough, ripping off “The Fugitive” became one of the favorite techniques for TV producers hoping to coax viewers into accepting a more fantastical show than they’d normally consider watching. Most famously, “The Incredible Hulk” was “The Fugitive” with a tabloid reporter standing in for the pursuing police detective, and the One-Armed Man transformed into a monstrous alter ego for the beleaguered protagonist, but there were plenty more where it came from: “Werewolf,” “The Immortal,” “The Visitor,” etc. Hell, even the TV shows spun off from Logan’s Run and Planet of the Apes borrowed as much from “The Fugitive” as they did from their acknowledged source material. What makes me think something similar might have been intended for Vampire, had it been picked up for series production, is the deeply weird state of affairs on which the pilot movie ends. When the titular bloodsucker is finally run to ground in the mausoleum where one of his backup coffins lies hidden, the showdown between him and his human enemies ends in a surprising stalemate, with the damsel in distress rescued, but the vampire escaping to resume his battle against the heroes another day. Normally I’d keep my mouth shut about that sort of thing, but I figure it’s only fair to warn you all that Vampire ends on a hook for a “sequel” that will never be made.

Anyway, we begin with the groundbreaking for a new Church of St. Sebastian, replacing the one that gradually slid into disrepair and disuse after its founding priest disappeared mysteriously during World War II. The San Francisco city government has high hopes for the place as a lynchpin for the renewal of the blighted Bryant Park neighborhood surrounding it— most of which, it’s quietly implied, will be bulldozed to make way for the middle-class-friendly appurtenances listed in the introductory speech by local politician Christopher Bell (Michael Tucker, from Eyes of Laura Mars). The ceremony is a bit weird, because the commencement of work is symbolized not by the usual turning over of the first shovelful of earth, but rather by the erection of an immense cross on the property. Stranger still is the effect of the sun hitting said cross once it’s securely in place. The ground where the shadow of the monument falls starts blackening and sizzling, emitting wisps of thin, white smoke! Nobody notices that, however, except ex-cop Harry Kilcoyne (E.G. Marshall, of Two Evil Eyes and The Tommyknockers), who as we shall see has a personal connection to the construction site. Then that night, when the sun is down and the premises are vacated, a man (Richard Lynch, from Curse of the Forty-Niner and Halloween) claws his way out of the smoldering dirt, plainly not in the best of moods. That very evening, Bryant Park and its adjacent downmarket neighborhoods begin suffering the depredations of a throat-slashing serial killer who leaves his victims almost completely drained of blood.

Some four weeks later, husband-and-wife architects John (Jason Miller, of Mommy and The Exorcist) and Leslie (Kathryn Harrold, from Nightwing and The Sender) Rawlins are throwing a party at their strangely institutional-looking uptown mansion, one guest at which is their mutual friend, high-rolling attorney Nicole De Camp (Jessica Walter, of Play Misty for Me and Home for the Holidays). It happens that the Rawlinses designed the Church of St. Sebastian and its associated community center, and will presumably have first refusal on any other project in the shady real estate bonanza to come in their wake. Nicole, meanwhile, has recently enjoyed a triumph of her own, albeit on a more personal front. She’s found herself a boyfriend. And not just any boyfriend, either, for Anton Voytek is a filthy-rich scion of Eastern European nobility. Naturally that means he’s also the vampire of the title, the man who was getting charbroiled in his hidden tomb during the preceding scene, and the Bryant Park throat-slasher, but neither Nicole nor Leslie nor John will be figuring any of that out for a while yet.

In the meantime, it’s fortuitous that Voytek’s romantic connections should bring him into contact with the Rawlinses, because he’s been trying to figure out whom he needs to talk to about a certain business proposition related to the Church of St. Sebastian construction site. The way he tells it, he’s technically the owner of the land in question; an ancestor of his (wink, wink, nudge, nudge) bought it back in 1938, when it became clear what the rise of Nazism was going to mean for the eastern half of Europe, but the whole family apart from Anton himself was exterminated before they got a chance to make much use of their American bolt-hole. Voytek could stake a claim that would tie up the entire project in litigation for who knows how long, but he’s far too wealthy to care about the land itself. No, Anton’s interest lies in something underneath the land, a secret vault which his doomed forebear constructed to house an art collection the Voyteks had been accumulating since the 12th century. There’s every chance that the vault and much of its contents were destroyed 30 years ago, when the abandoned old Heidegger mansion above it was demolished to make way for the squalid tenements that are now falling in turn before the city’s bulldozers, but when John and Leslie see a list of highlights from the lost Voytek collection, they understand at once just how priceless this opportunity really is.

The Rawlinses pull the necessary strings to get the work on St. Sebastian’s paused while they go looking for long-lost artistic treasures, but then Leslie’s research turns up something that throws an entirely new and altogether more sinister light on the situation. According to the gallery curators and art professors she consults, every item on Voytek’s list disappeared before the date when his ancestor supposedly hid it beneath the Heidegger estate. To all appearances, the trove that John and Leslie have agreed to help unearth is the product of a generational campaign of art theft spanning eight hundred years! That’s no reason to leave the stuff entombed, of course, but it certainly is reason enough to give Anton himself all the side-eye in the world. Then the excavation uncovers a skeleton which is identified as that of Father Maurice Bernier, the aforementioned vanished founder of the previous Church of St. Sebastian. Between a dead priest and roughly $25 million worth of stolen art, there’s just no way that Voytek doesn’t have a night of extremely uncomfortable conversations down at police headquarters ahead of him.

That’s annoying for Anton, but what troubles him more is the prospect of the following morning. It simply wouldn’t do to let sunrise catch him in a jail cell, away from his coffin. Fortunately, Nicole shows up to post his bail, but it’s just before dawn by the time she arrives, and Voytek had grown so desperate by that point that he was just about to take the insane risk of busting himself out the hard way, never mind the trail of eyewitnesses and bizarre physical evidence that doing so would leave behind. He reaches the secret coffin room in his high-rise apartment just as he’s beginning to look and smell like a rack of St. Louis spareribs. Still, even that just means one crummy night, and no vampire makes it through eight centuries without logging a few of those. Having the proceeds of ten human lifetimes’ worth of art heists impounded, though? That stings. That’s the kind of thing that no self-respecting undead boyar can shrug off. That’s a “hound those fuckers to the grave and beyond” sort of offense, and Voytek wastes no time at all in working out a revenge scheme worthy of it.

Step #1 is a visit to the Rawlins house while Leslie is alone in it— ostensibly to extend an offer of renewed friendship, but actually to hypno-seduce the unfortunate woman before feeding from her, killing her, and doing things to her corpse that can’t even be described without calling down the wrath of Standards & Practices. Step #2 is to amp up his supernatural hold on Nicole far enough to make her his unwillingly willing alibi when John plausibly fingers him as Leslie’s killer. Step #3 was probably never part of the plan, but is much too good an opportunity not to exploit: when Rawlins breaks into Voytek’s apartment in the hope of waylaying him, and accidentally catches the vampire emerging from his coffin come sundown, Anton calls the police on him! That leads not merely to John being jailed (he’s just lucky he’s such good friends with Christopher Bell…), but ultimately to his commitment to a mental hospital when he’s caught trying to break into Anton’s place a second time, bearing a cross, a hammer, and a sharpened wooden stake. Finally, step #4 is supposed to be the end for Rawlins, as the vampire drops in on him in the nuthouse, where the poor schmuck is too full of Thorazine to defend himself in any way…

But Voytek hasn’t figured on Harry Kilcoyne. The reason why the old cop was hanging around the St. Sebastian’s construction site in the first place was because he had been a close personal friend of Father Maurice Bernier. More than that, they’d been coworkers once, for Bernier was a policeman before he resigned to take holy orders. In 1939, the men had even been partners on a particularly harrowing case— a rash of throat-slitting murders eerie similar to the ones plaguing Bryant Park now. In some way that Kilcoyne never quite understood, that case provoked Bernier to switch vocations, and the ex-detective has no doubt that the priest was still trying to get to the bottom of it in his own way when he ventured fatally into the then-new catacombs beneath the Heidegger mansion. Kilcoyne has been thinking a lot these past several weeks about why the shadow of a cross should burn the ground where his friend died so mysteriously— ground which Bernier himself once told him felt suffused with ineffable evil. He’s been thinking a lot, too, about the M.O. of that killer he and Bernier never quite caught 40 years ago, and about how strange it is that a copycat murderer should emerge on exactly the same turf after all that time. And thanks to the connections he still maintains at his old precinct, he’s been thinking as well about the paraphernalia that crazy architect was carrying when he got carted off to the mental hospital. Kilcoyne doesn’t like where all this thinking lands him, mind you, but he’s too sharp a detective even now not to see how the pieces of the puzzle fit together. He decides to look in on Rawlins himself, and arrives at his cell just in time to thwart Anton Voytek’s attack.

Somehow or other, Kilcoyne manages to get Rawlins released into his custody, and the pair withdraw to Harry’s apartment to figure out what to do next. Kilcoyne tells Rawlins what he knows about the death of Father Bernier, and Rawlins eventually opens up enough to share the results of the research he’s been doing at various libraries and archives ever since he discovered what Voytek really is. John is reluctant to carry the partnership any further than that, but Harry soon convinces him that neither one of them stands a chance alone against a vampire with 800 years of practice in outwitting, outfighting, and outmaneuvering the living. Fortunately, Kilcoyne has a non-trivial amount of experience in finding people who’d rather stay hidden, and in trapping them at moments of maximal disadvantage; the plan he comes up with for taking the offensive against Voytek is as plausible as anything Dr. Van Helsing might have devised. It also has one critical weakness, however, of the sort that Voytek is just the sort of bastard to exploit. Harry has a neighbor, a single mother by the name of Andrea Parker (Nightmare in Blood’s Barrie Youngfellow), to whom he has become extremely attached since the death of his wife some years ago. For that matter, he might be even more attached to Andrea’s son, Tommy (Adam Farrar, from Conquest of Earth and Looker). Now a boy Tommy’s age can be moved out of the line of fire by sending him for an extended visit to his father in Arizona, but Andrea has the kind of adult responsibilities that preclude sudden departures to undisclosed, secure locations. She’d make an irresistibly tempting target for a flanking attack…

Make no mistake, Vampire is harmed somewhat by the inconclusive ending designed to facilitate a continuing series. Not only does it violate audience expectations (which, to be sure, is often a good thing), but it does so without warning, for reasons visibly extrinsic to the story being told in the pilot. The overwhelming feeling as the screen fades to black for the closing credits is, “Wait, damnit— we’re not done yet!” And while that’s exactly what one wants at the close of the first episode of a continuing television series, it’s an altogether different situation for a TV movie that has to stand on its own.

That said, I would definitely have tuned in next week, had there ever been a next week for Vampire. Although it is, in outline, just another Dracula riff— to the degree that you’ll quickly find yourself thinking, “Okay, you’re going to be Lucy, and you’re going to be Mina, and you’re going to be Van Helsing… Whoa! Didn’t expect you to be Renfield!”— the specifics put enough new spins on the material to keep it fresh and exciting. In particular, I love the mechanism that Bochco and Kozoll use to set the conflict in motion. Having had my fill a dozen times over of ancient vampires crossing oceans of time to seek out the reincarnation of some woman they loved in mortal life, how could I be anything but delighted to see one go to war against the guy who finally outed him after 800 years as the world’s greatest art thief? Similarly, there’s a lot to chew on in the implications of Voytek’s 30-odd years of inactivity, brought to a halt by the consecration of the ground where he’d allowed himself to be buried along with Maurice Bernier. Are we to take it that vampires don’t actually need to drink the blood of the living in any biological sense? And are we to picture the trapped Voytek lounging contentedly for decades among those of his treasures as survived the cave-in, like Smaug sleeping for centuries atop the King Under the Mountain’s hoard? Finally, although I’m almost certainly overthinking this, there’s some interesting subtext to be extracted from the fact that an urban renewal project stirs up the long-buried evil in Bryant Park.

What impressed me most about Vampire, though, was the interaction between Jason Miller’s performance and Richard Lynch’s. Miller here is pretty much what you’d expect from him on the basis of The Exorcist, but that’s just what the role calls for. Not many actors could put forward this particular strain of glum anguish so effectively, and it’s interesting to see Miller play a man broken by it, if only temporarily, in a way that Father Damien Karras never was. Lynch, meanwhile, manages something I never would have thought he had in him: he’s suave! That proves to be a disproportionately vital asset to Vampire, because so much of the film hinges upon Voytek’s ability to charm his victims, allies, and enemies alike. Underneath that slick and genteel surface, though, is the same sort of nasty, brutish heavy that Lynch played so often in movies like The Sword and the Sorcerer and Deathsport, and the actor turns out to be extraordinarily capable of calibrating how much of the slavering monster peaks out from behind the Continental sophisticate at any given moment. It really sells such tricky scenes as the seduction of Leslie Rawlins, whose passionate surrender to Voytek is unmistakably the result of the vampire’s telepathic puppeteering, and not anything originating within her own mind or heart. I’m sure we wouldn’t have seen much more of Lynch even if Vampire had gone to series (after all, the One-Armed Man showed up in person only ten times during the entire four-season run of “The Fugitive,”), but he makes Voytek such an impressive, memorable villain that I’m sure I would have found myself exclaiming, “Oh boy! This is going to be a good one!” every time “Special Guest Star: Richard Lynch” appeared in the opening credits of the show that never was.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact