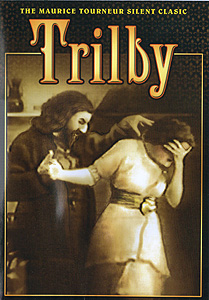

Trilby (1915) **

Trilby (1915) **

I don’t know whether literary critic Walter Kendrick actually invented the term “genrefication,” but his is the name that keeps coming up as I research the origins of the concept. I’m not talking merely about the age-old tendency of culture consumers to assign works of art to conventionalized categories of style and subject matter, and neither was Kendrick. Rather, this sense of genrefication refers to the process whereby those conceptual pigeonholes get built in the first place. On the surface, that might seem too simple and obvious to be worth analyzing— genres happen when a given work of art inspires a critical mass of creators to make more like it. Missing from that minimalist reading, though, is any appreciation for how very far from obvious the meaning of “others like it” can be. I touched upon this briefly in my review of The Drums of Jeopardy, observing that although the huge success of Dracula quickly provoked Universal’s rivals to release horror movies of their own, most of those rivals were slow to identify what had set Dracula apart from the likes of The Bat Whispers and The Unholy Night. Horror, that is, was not yet fully genrified in Hollywood in February of 1931, despite the existence of two and a half decades’ worth of what we would now retrospectively recognize as horror films. There were movies about mad scientists, about evil geniuses, about disfigured recidivist killers. There were films exploiting the eerie atmospheres of gothic mansions, of hostile wildernesses, of abandoned public spaces. There were screen adaptations of classic macabre literature by Robert Louis Stevenson, Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, Washington Irving, and so forth. But there was not yet a sense in this country that all of those things related to each other in any significant way, or that they therefore belonged together in a box marked “horror movies.” That realization dawned over the course of 1931, but it took a few more years to sort out what the essential elements of the newly recognized genre were— to establish, for example, why Svengali is a horror movie while The Mad Genius is not, even though the plots of the two films are virtually identical.

The contrast with The Mad Genius isn’t the only way in which Svengali is relevant to the genrefication of horror, either. The evolution-by-adaptation of George Du Maurier’s Trilby (the novel from which Svengali derives) can be viewed as a case of genrefication in action, as successive translations to non-print media placed ever more emphasis on the fantastic and macabre elements of the story, with the 1931 film being the first in the English language to treat it as a horror tale in something like the full, modern sense. (I specify English because I have yet to see the German version from 1927— if indeed it still survives. With Paul Wegener both directing and playing the title role, I’d expect that Teutonic Svengali to hit the horror aspects of the premise pretty hard.) Du Maurier’s Trilby, published serially in 1894 and in book form a year later, is more a study of the Parisian Latin Quarter arts scene in the mid-19th century than anything else. Its principal focus is on the love affair between a young English painter and a free-spirited Irish girl who models for the artists in the studio where he and his friends rent working space, and on how that affair is brought to grief by stodgy middle-class prejudices the boy never knew he had until it was too late. Svengali, far from meriting his name in the title, is a minor figure who swoops down in the aftermath of the breakup to heap a final dollop of misery on the two kids, like a stunted parody of a gothic villain from the preceding generation. He’s easily the most interesting character in the book, but he isn’t in very much of it. Stage and screen adaptors saw more clearly the potential that Du Maurier had left fallow, however, and wisely made Svengali’s role steadily larger, his villainy steadily more overt, and the nature of the hold he develops on Trilby (the model) steadily more uncanny, until by the early 1930’s, he was a Mephistopelian wizard, living like a parasite off of moneyed young women, and willing them to suicide once their usefulness to him was at an end. Maurice Tourneur’s version of Trilby, released in 1915, falls almost exactly at the halfway point between the 1890’s novel and the 1930’s film, and it also serves as a convenient halfway point along the trend-line from Du Maurier’s interpretation to Warner Brothers’. Its Svengali is more prominent than Du Maurier made him, but still remains a secondary character. His domination of Trilby seems a little more than natural, but doesn’t quite rise to the level of black magic or paranormal mind-power. And although much is made of his nefarious designs on the young model, there’s something strangely small-time about them in practice. Even at his worst, this Svengali is a nuisance and a creep more than a full-fledged evildoer.

The Latin Quarter: seat of learning, capital of the arts, focal point of the international counterculture known somewhat counterintuitively as la bohème. Among the aesthetic adventurers drawn to this global nexus of creativity and libertinism are a trio of British painters, of varying degrees of seriousness and skill. Taffy (James Young) and the Scotsman known only as “the Laird” (D. J. Flanagan) are mere dilettantes, attracted to the Latin Quarter more for its stimulating social life than for the opportunities it offers for honing their inconsequential talents. Their younger friend, Billie (The Submarine Eye’s Chester Barnett, who starred opposite Pearl White about 100,000 times during the 1910’s), on the other hand, has real ability. The studio they rent together is home to many other artists, of seemingly every discipline, but the only ones we need pay attention to are a Judeo-Slavic music-master by the inexplicable penny-dreadful Italian name of Svengali (Wilton Lackaye, reprising a role he’d played to much acclaim on the stage) and his violinist protégé, Gecko (Paul McAllister, later of The Invisible Ray). Ever been part of a social circle where there was one person who always seemed to be hanging around, even though nobody else really liked him, and no one would claim him specifically as their friend? Well, that’s pretty much how it is with the painters and Svengali. He’s a mooch and an overbearing jackass, and he avoids bathing the way a vampire avoids fresh garlic, yet neither Billie, Taffy, nor the Laird shows any strong inclination to be rid of him.

One day, while Svengali and Gecko are hanging out with the Brits, boisterously extemporizing music on piano, violin, and improvised percussion, the commotion catches the ear of Trilby O’Farrall (Clara Kimball Young, from The Return of Chandu and Lola) as she poses for the sculptor who rents the space across the corridor. As soon as her client is able to part with her, Trilby heads over and joins the party. The girl passionately loves singing, but unfortunately she’s absolutely dreadful at it. Completely tone-deaf, but possessed of a powerful, projecting voice in a register that cuts through even the densest competing sound, Trilby can wreck in a single measure any harmony the human mind can devise. Svengali is fascinated by her, because according to his expert ear, she has all the physical attributes of a world-class soprano; it’s just her inability to hear the difference between, say, 50 hertz and 5000 that leaves her sounding like a cockfight in a kindergarten. Billie is fascinated by Trilby too, but the point of interest for him is rather more mundane— she’s a pretty girl, and he hasn’t got one of those.

19th-century literature was waist-deep in stories about artists and models falling for each other, and it seems like every last one of them eventually came around to the same dilemma: what’s a girl to do when practicing her profession regularly requires semi-public nudity, but her entire culture is suffering from a crippling Madonna-whore complex? Trilby’s romance with Billie seems to be burgeoning nicely until he walks in on her sitting for a whole roomful of other painters. You might think Billie would be prepared for such an eventuality. I mean, he knows she’s an artists’ model. As an artist himself, he has to know what artists’ models do. Surely it can’t help but have crossed his mind at some point that Trilby must therefore do herself what artists’ models do as a class. But since Billie hails from a society that’s mouth-frothing insane about everything even tangentially related to sex, his “discovery” that Trilby gets paid to exhibit her naked body to men becomes a relationship-smashing trauma, even though he discovers nothing he didn’t already know, were he to be honest with himself for ten fucking seconds. That gives Svengali an in for a plot that we don’t as yet realize he’s forming. Naturally it’s a stressful thing having your lover unjustly forsake you for being a shameless hussy, and the neuralgia that Trilby has suffered from since she was a child starts acting up more and more in the aftermath. Because she remains friends with Taffy and the Laird, and because they remain insufficiently motivated to tell Svengali where to stuff it, the latter happens to be on hand one afternoon when Trilby is overcome by one of her headaches. Svengali, revealing for the first time that he’s a mesmerist as well as a musical genius, offers to cure her suffering via post-hypnotic suggestion, and it would appear that he sneaks in a few extra instructions beyond “no more neuralgia” while he has her in a trance. From that moment forward, Svengali has but to execute a few quick gestures in front of Trilby’s face to put her under again. Why do such a thing, you ask? Because he believes that the same mental mechanism whereby he relieved the girl’s headache can also overcome her tone-deafness, allowing him to make of her the greatest singer of her generation, and to cover himself with reflected glory in doing so. Trilby’s subsequent reconciliation with Billie puts a kink in that plan, but only a small one. If Svengali can hypnotize Trilby into singing like a nightingale, then he can certainly hypnotize her into breaking her engagement to the painter as well.

Maurice Tourneur has a reputation today as one of the early masters of cinema, but I can find very little basis for such an assessment in Trilby. Of course, feature filmmaking as we now understand it was still in its infancy in 1915, and there is much cause to believe that this movie’s weaknesses stem more from the immaturity of the medium than from any faults of Tourneur’s specifically. Trilby’s main defect is that it presupposes too much familiarity with the source novel. Take the business about Trilby’s singing voice, for example. The only indication of the natural endowments that lead Svengali to believe he can use her despite her inability to carry a tune is a bizarre moment during their first scene together, when he seizes her by the chin and peers closely into her open mouth. Having read the book, I know that he’s studying the architecture of her hard palate, impressed by the raw power of her voice. In the movie, however, that action goes completely unexplained. Nor is there any description of Trilby’s singing beyond her own admission that she’s tone-deaf, so that when Svengali later begins talking about turning her into a diva, the natural audience response is not, “Ooh— hypno-pedagogy!” but rather, “Wait— what?! But you said yourself she was terrible!” The lack of clarity is a problem in more ways than the obvious, too, because the harder it is to tell what’s going on, the harder it usually is to give a shit— especially when it looks like there’s nothing going on but a bunch of stuffy Victorians standing around the set striking poses at each other. More and better intertitles would have helped substantially in putting the key ideas across, which is a major reason why I’m inclined to blame the times more than Tourneur or scenarist E. Magnus Ingleton. From what I’ve seen, movies from this era frequently suffered from overly optimistic assumptions about how much information was being conveyed by the action onscreen; only the true visionaries seemed to understand as yet that storytelling techniques developed for the one-reelers would no longer suffice now that a typical movie’s running time was becoming measurable in hours. The same thing goes for Trilby’s clunky editing and static shot composition, both of which are completely normal for a movie this old. In fact, the latter is where I find cause to praise Tourneur a bit, because there’s one moment early on where he decisively breaks with the still-conventional “stage play on film” approach— a nifty camera pan across the entire room during the shot that establishes Billie, Taffy, and the Laird in their studio. It isn’t as impressive as the tracking shot down the Carthaginian street in Cabiria, but it is a sign of growth in technique, and an affirmative virtue in a film that could use a few more of those.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact