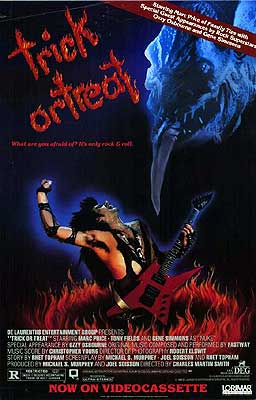

Trick or Treat (1986) -***

Trick or Treat (1986) -***

A lesson in the unreliability of unaided memory: If you had asked me fifteen years or so ago to describe The Gate, I’d have said something like, “That’s the one where two boys, one of them a precocious headbanger, accidentally raise a Satanic heavy metal band from the dead by playing their last album backwards. The band plays a concert that turns the audience into demonically possessed murder zombies, but fortunately a different backmasked track on the album reveals how to send the undead rockers back to Hell. Oh— and I’m pretty sure Alice Cooper plays the lead singer.” And if I had said that, I would have been almost completely wrong. Parts of that misremembered synopsis came from The Gate alright, but as I figured out while plotting the lineup for the Satanic Panic update I posted in the fall of 2014, a lot of it came from some other movie altogether— Black Roses in particular. There had to be something else in the mix too, though, because when I watched those two films for review, there were still elements of my imaginary composite heavy metal horror flick unaccounted for— elements that I recalled too distinctly to have made up out of nothing. Well, now I know where those pieces really came from. The dead devil-rocker brought back to life by magic backmasked into his final album is the villain from Trick or Treat, and damned if he doesn’t look a bit like Alice Cooper, if somebody in a harsh climate left him out on the back porch all summer. Furthermore, although the real Cooper doesn’t put in an appearance, Gene Simmons and Ozzy Osbourne do.

Eddie “Ragman” Weinbauer (Marc Price, from Little Devils: The Birth and Killer Tomatoes Eat France!) is a troubled kid. His father is out of the picture, his indulgent mother (Motel Hell’s Elaine Joyce) doesn’t really understand him, and his nerdy pal, Roger Mockus (Glen Morgan), is the only kid at school who doesn’t treat him like he has leprosy. Leslie Graham (Lisa Orgolini), the object of Eddie’s romantic obsessions, barely seems to know he exists, and the pack of jocks led by Tim Hainey (Doug Savant, of Teen Wolf and Maniac Cop 3: Badge of Silence) see to it that each new day is an all-Eddie-can-eat buffet of humiliation. The only thing Eddie has found that seems to bring sense or meaning to his life is heavy metal music, especially that of outspoken egoist and Satanist Sammi Curr (Tony Fields). When Curr sings about rock-and-roll warriors ruling the apocalypse, he gives voice to nihilistic fantasies that Eddie never figured out how to articulate for himself. Curr’s widely publicized clashes with media scolds like the Reverend Aaron Gilstrom (Ozzy Osbourne, playing as diametrically against type as you can possibly imagine) are for Eddie nothing less than skirmishes in a war for control of the future. It’s worth noting that Eddie’s idol-worship is based on a connection more personal than the typical case of an overeager fan reading too much into the music of his favorite artist. Sammi Curr was a hometown boy before he made it big; he even attended Lakeridge High School, where he presumably faced whatever equivalent to Weinbauer’s travails was current in the mid-1960’s. So perhaps you can understand how devastating it is for the boy when his hero is killed in a fire that guts most of the hotel where he’d been staying.

Roger may be Eddie’s only friend at school, but he isn’t quite Eddie’s only friend. Years of concert-going, record-shop-haunting, and frequent call-ins to WZLP, Lakeridge’s independent FM rock-radio station, have brought him surprisingly close to Nuke (Gene Simmons, whose other forays into acting include Runaway and— unsurprisingly— Kiss Meets the Phantom of the Park), the DJ who hosts said station’s metal show. Nuke also went to Lakeridge High back when, and he knew Sammi Curr personally. They still keep in touch, too, so it’s only natural that Nuke would be the person to whom Eddie turns in his grief. It happens that Nuke has something that might assuage the boy’s sense of loss just a bit. Curr was working on a new album when he died, to be called Songs in the Key of Death. (Wow— that’s not prescient or anything…) He got as far as cutting an acetate master of the studio demo, and the last time he came by to visit Nuke— presumably while he and his agent were negotiating their ultimately failed attempt to book Curr and his band to play Lakeridge High’s Halloween dance this year as a special favor to the hometown kids— he lent him that very disc. As soon as word of the fire got out, Nuke decided that he was going to play the demo on WZLP at midnight on Halloween Night, and he’s already transferred Songs in the Key of Death to tape for that purpose. Under the circumstances, Nuke figures there’s probably nobody whom Sammi would rather have the original acetate than Eddie. Weinbauer may have lost his idol, but now he’ll have one of only two extant copies of his last musical testament. (I won’t tell the screenwriters about the studio tape reels if you won’t…)

Another bit of unexpected good news greets Eddie at school that day. The coveted Leslie Graham witnessed an especially shitty act of hazing against him earlier in the week, and compassion has moved her to try vicariously making it up to him, a bit like Carrie’s Sue Snell. Indeed, Leslie goes so far as to invite Eddie to the after-hours party she’s throwing at the community swimming pool which her family apparently owns. Alas, that doesn’t go well. Tim and his crew are in attendance too, and what they do to Eddie this time— tossing him into the pool with a heavy weight stuffed into his backpack— is potentially life-threatening, even if they do have the consideration to throw him into the shallow end. That it’s Leslie who jumps in to rescue him is arguably even worse, socially speaking, given the typical high school boy’s unenlightened conception of manly honor. Eddie leaves the party vowing revenge.

That remains the boy’s mood when he notices the first backmasked message on Songs in the Key of Death. Eddie falls asleep listening to the demo, and awakens from a dream of Sammi Curr performing some manner of fire-related ritual in the middle of an orgy in a hotel room to find his record player skipping on a closed groove, repeating the same garbled phrase over and over. Reversing the turntable reveals Curr’s voice hissing, “Let the big fish hook themselves. You’re the bait!”— and suddenly Eddie knows exactly what to do about Hainey and his goons. The next day, during lunch, Eddie provokes Tim into a fight, leads him on a slapstick chase along a pre-plotted obstacle course through the school’s corridors, rooms, and stairwells, and ultimately tricks him into turning a fire extinguisher on a group of teachers gathered in the staff lounge. I believe that’s called “detention until the heat death of the universe.” Roger dismisses the admittedly pretty brilliant inspiration as a coincidence, but Eddie’s sense that Sammi Curr is somehow looking out for him from beyond the grave only intensifies as he discovers more (and more seemingly direct) backmasked messages hidden throughout Songs in the Key of Death. Weinbauer even attributes it to the dead rocker’s intervention when an inexplicable machinery malfunction turns the tables on Hainey a second time after he and his pals corner Eddie in the school’s metal shop. (I say again, its metal shop…) The notion of Curr’s supernatural guidance and protection gives Eddie a sense of power unlike anything he’s ever felt in his life, together with an arrogant species of confidence which Mom and Roger alike are perceptive enough to find troubling.

Nevertheless, Weinbauer knows that his escalating feud with Hainey has to be brought to some decisive end. Somehow or other, Eddie gets it into his head that the way to do so is to make his enemy a cassette copy of Songs in the Key of Death— although it’s clear from subsequent events that he has no conscious idea of what he expects to accomplish thereby. What ends up happening is that Tim never listens to the tape at all. However, his girlfriend, Genie (Elise Richards), does. The two of them are parking on lovers’ lane, and when Tim stumbles off to piss out about a case of cheap beer, Genie puts Eddie’s tape into her Walkman to pass the time. The music conjures up an incubus which violently rapes her, leaving her in a coma. Hainey doesn’t witness the attack itself, but he puts two and two together when he sees what she’d been listening to— he just isn’t sure what, exactly, they add up to. Intuiting that Weinbauer is preternaturally responsible for his girlfriend’s condition certainly doesn’t help Tim understand or explain the situation, let alone do anything about it beyond raging impotently at Eddie from a presumably safe distance.

Eddie is able to extract enough sense from Tim’s rant to realize that this whole business has just gone much further than he ever wanted. But he gets a big, unwelcome surprise when he cues up Songs in the Key of Death in the hope of talking his guardian devil down. This time, Curr puts in a personal appearance, manifesting physically in Eddie’s bedroom as a sort of electric revenant to announce that he’s only just begun his offensive against the forces of order and conformity. You remember that show he was forbidden to put on at the high school on Halloween? Well, Sammi means to play it after all, and Eddie won’t let his sudden onset of cold feet provoke him into doing anything as foolish as trying to stop it— not if he knows what’s good for him, anyway. “You should respect your heroes,” the resurrected rocker warns, “They might turn on you.”

I’m not going to pretend to you that Trick or Treat isn’t goofy as fuck. In the final assessment, this is a movie that climaxes with a sad, poodle-haired Blackie Lawless wannabe blowing people bloodlessly to kingdom come with lightning bolts fired from the headstock of his guitar. At its core, Trick or Treat is every inch as silly as Black Roses. However, that makes it all the more noteworthy that it’s a vastly better film on the surface, and even a bit below. Effort and money were put into this thing on a scale wholly disproportionate to the merits of the premise, beginning all the way back at script level. The writers of Trick or Treat got some things right that I wouldn’t even have expected them to care about. Most importantly, they and Marc Price between them offer a fully believable rendition of an adolescent outcast who one day gets his hands on some back-channel power, and lets it go dangerously to his head. That was me in ninth grade (although obviously my classmates just thought I was a devil-worshipping, axe-murdering warlock), so you can trust me when I say that Trick or Treat accurately captures the subjective experience of discovering that kids who have the strength to prey on you with impunity, and/or the influence to wreck your social prospects for years with a single sentence, are suddenly afraid of you. It’s unusual, too, that someone like Eddie Weinbauer not only gets to be the protagonist of this story, but doesn’t have to become “normal” in order to win redemption for his role in unleashing supernatural evil.

Moving forward in the production cycle, Trick or Treat is well and even cleverly cast. One thing you’ll notice immediately is that its teenagers seem much more plausibly teenaged than their counterparts in most other contemporary movies set in and around American high schools. That’s because the vast majority of the actors playing them were considerably younger than the pushing-30 “juveniles” we’re used to seeing, and Marc Price really was only eighteen. That’s a big part of what makes Eddie potentially sympathetic in spite of everything, and even goes some way toward making his enemies seem less irredeemable than they otherwise might. (Another point of commonality between Trick or Treat and The Gate, I might add.) The stunt-cast rock stars are smartly deployed, too. The irony of Ozzy Osbourne playing a Pat Robertson figure is compellingly transgressive in both directions, and Osbourne wasn’t yet such an abject drug disaster in 1986 that he couldn’t hold himself together for a few short scenes with a couple lines of dialogue apiece. Gene Simmons, meanwhile, had already displayed some acting chops before this, so it’s less of a surprise to see him so ably delineate the difference between Nuke’s flamboyant on-air persona and the more grounded demeanor he adopts when the microphone is turned off. And although she’s a small enough presence that her importance is easy to undersell, Elaine Joyce makes for one of the better B-movie mothers of the era, concerned yet clueless, loving yet sufficiently wrapped up in her own affairs to miss a whole barrage of warning signs, sensing that she’s supposed to get tough with her wayward son, but so temperamentally unsuited to playing the disciplinarian that she doesn’t know where to begin.

Finally, a bit of measured praise for director Charles Martin Smith. Trick or Treat was his first film in that capacity (his Internet Movie Database page suggests that he’s a character actor first and foremost), and although Smith’s work here is nothing to get excited about, it’s more than merely competent. He maintains a good pace, consistently gives the images onscreen some degree of visual interest, and displays a knack for making exposition look like something else less labor-intensive. To all outward appearances, he worked well with both the cast and cinematographer Robert Elswit, whether that meant giving them what they needed or just getting out of their way. If Smith was ultimately unable to save Trick or Treat from itself, well… We all know that’s the hardest kind of saving there is to do, right? At least he managed to maneuver this movie onto an entertaining path before its descent into farce went ballistic.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact