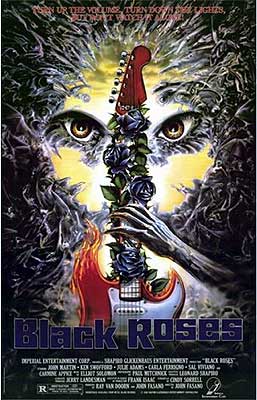

Black Roses (1988) -**

Black Roses (1988) -**

I don’t normally do this, but it really does seem like the most parsimonious approach to the problem. Before you delve any deeper into in this update, go read at least the first three paragraphs of my old Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare review. All the films I’m covering this time around were informed in one way or another by the Satanic Panic of the 1980’s, and I think I’m unlikely to come up with a better intro to the topic than that one. It seems partcularly apt to reference Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare in a review of Black Roses, too, because several key personnel— director John Fasano, actor Frank Dietz, seemingly the entire Cirile family, who filled a range of positions on either side of the cameras— were involved in making both movies. That connection raises some questions, however, because the two pictures seem at first glance to be philosophically at odds. Whereas Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare strikes an artless blow against the Satanic Panic by making the frontman of its cock-rock metal band an archangel in disguise, Black Roses goes the purely conventional route with a diabolical band turning a small town’s teenagers into subhuman monsters. What’s with the side-switching, especially since the subculture that Black Roses literally demonizes is unmistakably also its target audience?

To understand what’s going on here, you have to realize that “speculative fiction” isn’t always just a synonym for science fiction. Horror can be speculative, too, even when it has nothing to do with alien invasions or science run amok. It’s just that speculation in horror isn’t as freewheeling. When horror asks “What if?”, it very often ends up meaning specifically “What if this or that bunch of scaremongers, worrywarts, or party-poopers were right?” The writers or filmmakers needn’t necessarily agree with the positions they adopt— they simply recognize a particular brand of alarmism as fertile ground for a story. Think of it as a special form of the genre’s general tendency to take cues from the anxieties of the culture at large. Some widespread anxieties are more plausible than others, however, and there’s great fun to be had in treating the sillier ones with a gravity that they don’t properly deserve. So we shouldn’t be surprised to see, in the days of the Satanic Panic, horror movies that were willing to follow the Christian supremacist demagogues and their quack psychiatrist allies down even the goofiest rabbit-holes, all the way to the patently absurd notion of heavy metal music as a recruitment tool for the Satanic conspiracy. With one conspicuous exception, the films I’m reviewing this time out— Black Roses included— are best interpreted in that light. They’re neither conscious satires on pop-culture alarmism nor sincere contributors to it, but rather the result of people playing around with something that was already on everybody’s mind at the time.

Nothing cool ever happens in the little town of Mill Basin— just ask the teenagers toward whom Matthew Moorhouse (John Martin, from Night Game and Praying Mantis) teaches high school English without notable success. Those kids are so chronically bored that they have to amuse themselves by imaging a torrid affair between Mr. Moorhouse and his star pupil (for values of “star” approximating “shows up, pays attention, and does her homework most of the time”), Julie Windham (Karen Planden). But early one morning, a pair of Lamborghinis pull to a stop on otherwise deserted Main Street, and disgorge a quartet of heavy metal hair farmers who proceed to blanket the walls, lampposts, and utility poles with posters advertising a series of concerts by Black Roses. Who? John Pratt (Frank Dietz, of Zombie Nightmare and The Lost Skeleton Returns Again) knows who I’m talking about. Black Roses are the hottest, wildest, most controversial rock and roll act in the country, but up to now, they’ve operated almost exclusively as a studio project. There was supposedly one live performance a few years ago, but it’s so heavily shrouded in mystery and contradictory hearsay that it might as well not have happened at all. And now they’re coming to Mill Basin, of all places!

Mind you, not everybody in town is as excited by that prospect as Pratt and his no-good friend, Tony Ames (Tony Bua). A parents’ group led by Mrs. Miller (Julie Adams, of Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Underwater City) is lobbying hard to shut the concerts down, decrying Black Roses and their outspoken frontman, Damian (Sal Viviano, from The Jitters), as an antisocial influence. To hear Mrs. Miller tell it, to allow Black Roses into Mill Basin is to invite the indoctrination of the local youth with libertinism, diabolism, and anarchy. Rather surprisingly, however, Mayor Farnsworth (Ken Swofford, of Common Law Cabin and Hunter’s Blood) is in the band’s corner. For one thing, he isn’t so far out of touch that he doesn’t remember how his own elders reacted to the first efflorescence of rock and roll— or, for that matter, how Mrs. Miller’s elders reacted to the dance crazes of the swing era. And just as importantly, it isn’t often that out-of-towners express interest in bringing business to Mill Basin. Think what it could do for the local economy if Mill Basin became known as a welcoming place for touring musicians interested in road-testing new material away from the unforgiving gaze of big-city audiences! Eventually, Farnsworth works out a compromise whereby Black Roses will play a heavily chaperoned trial concert, proceeding with the rest of the schedule only if Mrs. Miller and her followers are satisfied that Damian and company aren’t leading Mill Basin’s teens into perdition.

Imagine everyone’s astonishment when Black Roses take the stage at their probationary show, and turn out to be the squarest thing since Lionel Ritchie. Mrs. Miller wishes they weren’t quite so loud, but even she agrees before the first song is finished that they’re probably too boring to do any real harm. Farnsworth, Moorhouse (representing the interests of the high school), and the Paranoid Parents pack up and leave Black Roses and the kids to their own devices… and suddenly the band stops playing. With all the tut-tutting adults safely out of the picture, Black Roses peel off their pastel dork suits to reveal the expected array of leather and spandex, and trade in the Light FM wimp rock for something more befitting of those permed mullets and shaggy chests. And as the show approaches its climax, the kids in the audience begin transforming, too, turning in the blink of an eye into slavering, rubber-faced zombies.

Come morning, there’s no outward sign of anything wrong with Mill Basin’s teens save the usual side effects of getting up early after staying out late. As Moorhouse soon discovers, though, they’ve all received something of an attitude adjustment. Matthew might have thought his students were difficult before, but now they’re absolutely intractable— even Julie Windham. Moorhouse knows the band is somehow responsible, but he’s unable to catch them at anything when he drops in on their rehearsal that afternoon. Nor does a visit to Mayor Farnsworth gain Matthew anything beyond an argument with the mayor’s daughter, Priscilla (Carla Ferrigno— Lou’s wife— from The Seven Magnificent Gladiators and The Adventures of Hercules), who used to be the teacher’s girlfriend as well. Black Roses’ second show in Mill Basin therefore goes on unopposed, with considerably more serious results. This time, the kids come home downright psychotic. Tony Ames runs over his mother in the driveway. (His dad— played by Vincent Pastore, of Torture Chamber and Return to Sleepaway Camp— was dispatched earlier in the day by Tony’s demon-possessed stereo.) John Pratt shoots his father (Jason Logan, from Satan’s Storybook and The Invisible Maniac) in the face with his own pistol. Mr. Miller (David Crichton) meets one of the more pleasant ends depicted here when his daughter (Pat Strelioff) has her friend, Tina (Robin Stewart), over while Mom is out at one of her Paranoid Parents meetings, and the latter girl apparently dry-humps him to death. Even sweet little Julie gets in on the antisocial action, first giving her own step-dad (My Bloody Valentine’s Paul Kelman) the seduce-and-destroy treatment, and then lying in wait to administer the old killer-in-the-back-seat routine to Priscilla. Finally, Julie comes after Matthew, and seeing his favorite student turn into an amorous cat-monster right before his eyes convinces Moorhouse at last that there’s nothing else for it but to return to the concert hall and go on the attack.

In retrospect, the most charmingly silly thing about Black Roses is the reminder that in the 80’s, social conservatives were sincerely terrified of heavy metal. And not even the Slayer-Venom-Death continuum of metal, either, which mostly flew underneath those folks’ radar. No, when preachers, politicians, and pushers of propriety railed against the Satanic scourge of heavy metal in those days, they were thinking about goobers like Bang Tango, Lizzie Borden, and King Kobra (whose founding members, Carmine Appice, Mark Free, and Mick Sweda, make up half of the pickup band we hear whenever Black Roses are playing). When Black Roses revels in the music’s demonic reputation by portraying the titular band’s concerts as everything the Jerry Falwells of the world were afraid of, it’s impossible not to laugh at such a quaint notion of evil, even before the cheesy rubber monsters show up. For that matter, it seems just as quaint and silly if we substitute “youth rebellion” for “evil” in that sentence— which, after all, was what the Moral Majority types were really upset about, anyway, beneath their Medieval framing of the issue. Of course, the quaintness and silliness should have been obvious to those with eyes to see even in 1988. Indeed, that was a big part of why I became a punk instead of a headbanger. Once you looked past the pentagrams and cloven hooves (which, to be fair, did appeal to my sense of showmanship), metal in the late 80’s had little to offer besides hedonism, whereas punk rock had hedonism and critiques of capitalism, patriarchy, bigotry, war, and neo-colonial foreign policy.

But to return to Black Roses, there’s plenty wrong with this movie even if you’re completely willing to roll with its premise. In fact, Black Roses is bad in pretty much every way that it’s possible for a film to be bad. That will not surprise those who recognize the names from Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare in the credits. Like that infamous shit-show, Black Roses is to a great extent an exhibition of profoundly embarrassing monster puppets, even if none of those here are quite equal to Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare’s legendary immobile Satan. It suffers further from some of the most thoroughly incompetent camera-work I’ve ever seen, offering not a single shot that is pleasing to the eye, and many that are affronts to both narrative sense and aesthetic sensibility. The dialogue is witless from beginning to end, especially when writer Cindy Cirile is trying to make Damian sound threatening to either the morals of the community or the safety of its would-be protectors. And the acting by everyone save Julie Adams is simply not to be believed— although the audition footage included as an extra on the Synapse DVD suggests that the filmmakers genuinely made the best casting choices available to them. (I would, however, love to see the parallel universe version of Black Roses in which the one guy who looks like he just came in to bother the casting director for spare change got the role of Damian.) But what makes Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare a minor anti-classic sadly cannot work the same magic on Black Roses. The sorry rubber beasties (with the commendable exception of the stereo demon) are too conventional to be endearing in spite of their lousiness. The players underact, so that no performance comes close to matching the sublime awfulness of the earlier film’s fake Aussie drummer, and most viewers will come away with a startling new appreciation for the lunkheaded charm of Jon-Mikl Thor. And most of all, Black Roses lacks the sheer bonkers weirdness of its predecessor. A heavy metal archangel posing as a slasher movie Final Boy was something unique and memorable, but any fool could cycle through the clichés of the Satanic Panic.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact