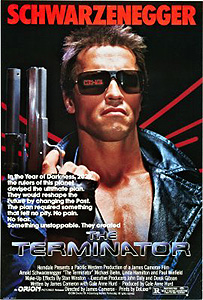

The Terminator (1984) ****

The Terminator (1984) ****

Now that he’s comfortably ensconced in the governor’s mansion in California, with twenty years as a household name and a box office miracle worker behind him, it takes a real effort of imagination to grasp the idea that once upon a time, Arnold Schwarzenegger was merely one more retired bodybuilder following in the sandaled footsteps of Steve Reeves and Reg Park, trading in his Speedos and baby oil for a sword and a loincloth. And considering that not even weekly television appearances as the Incredible Hulk were enough to keep Schwarzenegger’s old rival, Lou Ferrigno, in the public eye for more than a handful of years, while Reeves, Park, and their contemporaries had to go all the way to Italy to make the jump to the silver screen, the sudden runaway success of Arnold the Barbarian cries out for an explanation. James Cameron’s The Terminator is just about all the explanation you’ll need. Nevermind that Schwarzenegger only has about fifteen lines over the course of nearly two hours. Nevermind that his performance here consists of nothing more than marching around Los Angeles looking like the biggest imaginable bad-ass. He landed the title role in one of the finest sci-fi action movies of the 1980’s, and he carried it off seemingly without effort, solely on the strength of his extraordinary screen presence. From then until the turn of the 21st century, there would be no stopping Arnold Schwarzenegger.

For that matter, James Cameron himself was something of a bolt from the blue in 1984. Certainly nobody ever saw Piranha II: The Spawning and said, “That kid’s got a bright future ahead of him— just you watch!” Yet somehow, with his second feature film as a director, Cameron hit one out of the park and became one of the biggest names in the business. The budgets he was given to work with swelled as if they were following the formula for exponential growth, until eventually they reached levels that would have given even Dino De Laurentiis pause. More importantly, the box office performance of Cameron’s movies showed that the studios’ trust in his instincts was well-founded. For the rest of the decade and well into the one thereafter, Cameron was the go-to guy for a genre that is all but extinct today— the big, smart action film.

The year is 2029, roughly a generation after the nuclear war that came within an ace of wiping humanity from the face of the Earth. Slow-flying aircraft and huge, tank-like land vehicles pick through the charred skeleton of Los Angeles, crushing the similarly charred skeletons of its former inhabitants beneath their landing gears and caterpillar treads, firing on any living thing that crosses their paths. The final war, you see, was not precisely the showdown between East and West which had hung like the sword of Damocles over the second half of the 20th century, although there was indeed a massive, worldwide exchange of nuclear weaponry. Rather, the war was the devious culmination of a deliberate attempt by Skynet— NATO’s fully integrated, artificially intelligent strategic defense system— to exterminate its creators, their rivals, and indeed any other carbon-based lifeform with sufficient intelligence to pose a threat to it. Think of it as a sort of worst-case extrapolation from Colossus: The Forbin Project.

Now jump back 45 years. An LA trash collector working the night shift is interrupted by a flash of intense light, an outburst of lightning-like discharges, and an electromagnetic pulse that stops the motor in his compactor truck right in the middle of lifting up an apartment complex’s dumpster. When the strange disturbances cease, an enormous, nude man (Schwarzenegger) is standing in the middle of the street. He takes a moment to get his bearings, and then walks off in the direction of the hilltop observation deck where a trio of punk rockers (led by Bill Paxton, of Near Dark and Mortuary) are hanging out beside one of the coin-operated telescopes. The huge guy demands that they give him their clothes, but what they give him instead is the sharp ends of their switchblades. The strange man is not apparently bothered by a couple of stab wounds, however, and he overcomes his assailants within seconds, killing two of them with his bare hands. The third punk (who, luckily for the huge guy, just happens to be wearing an outfit about four sizes too big for him) loses interest in the fight pretty quickly after that.

Meanwhile, in an alley elsewhere in the city, the curious electrical phenomenon recurs, and another naked man pops up out of nowhere. This one (Michael Biehn, from Aliens and The Fan) is much smaller than the other— in fact, you could almost call him scrawny were it not for a certain wiry muscularity about him— and his entire body is covered with the scars of what look to have been some pretty nasty injuries. Rather than finding a gang of hooligans to kill and strip, the skinny guy contents himself with stealing the pants off of a drunken bum. He is caught in the act by the police, but manages to lose them in a nearby department store, where he also scrapes together enough odds and ends to finish dressing. Then he helps himself to a pistol and a riot gun lifted from the passenger compartment of an unoccupied prowl car. Finally, he hotwires a battered late-70’s Ford LTD (very much like the one I used to drive during my college years, as a matter of fact), pulls up beside a construction site, and falls into a shallow sleep troubled by dreams of giant drone war machines.

The next morning, both men find telephone books, and extract the page with listings for the name “Connor.” The huge guy then swings by a gun shop, where he assembles more firepower than the whole Panamanian army; he pays the man working the counter (Dick Miller, from The Premature Burial and The Young Nurses) with a shotgun shell to the chest. His next stop is the home of Sarah Ann Connor, whom he guns down the moment she acknowledges that that is in fact her name. He hits Sarah Louise Connor not much later. The city’s third Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton, from Children of the Corn and King Kong Lives), a young and not particularly competent waitress at a Big Boy-like restaurant, hears about the death of her first namesake on the TV news that afternoon, but initially thinks nothing of it.

The significance of that strange coincidence makes itself felt during the evening, however. Not only has Sarah #3 learned about the second killing by that point, she’s also noticed that there is a man following her around town. Sure, Sarah’s discreet shadow is the skinny guy and not the huge one who murdered the other two women, but she doesn’t know that, nor is there any very good reason as yet to assume that only the big guy means her harm. Sarah ducks into a dance club called Tech Noir, loses herself in the crowd, and places a call to her roommate, Ginger (Bess Motta). Ginger is too busy screwing her boyfriend (Rick Rossovich, of Warning Sign and Black Scorpion) to pay attention to the frantic voice recording itself on the answering machine, though, and she is taken totally by surprise when the killer comes by to complete the set. He ventilates both Ginger and Matt, and then notices the answering machine message from Sarah, giving both the name and location of the nightclub where she’s currently hiding out. Meanwhile, the killer’s intended prey has finally managed to get through to Lieutenant Traxler of the Los Angeles Police Department (Paul Winfield, from Damnation Alley and The Serpent and the Rainbow) with her story of being pursued by a suspicious stranger. Traxler promises to send some men around to Tech Noir to pick her up, but the huge guy gets there first. Sarah’s just lucky that the skinny guy has caught up to her; the two men begin shooting it out with each other, giving her a chance to escape immediate death. She also catches on pretty quickly that the man she had taken for a stalker is hell-bent on protecting her for some reason, and she hesitates for only a moment when he admonishes her to come with him. The escape is a narrow one, but it is more or less successful— at least for the time being.

Now how about some answers, eh? The skinny guy explains that his name is Sergeant Kyle Reese, and that he has come from the future. The huge guy is also from the future, and what’s more, he’s not a man but a Terminator, a cyborg warrior in the service of Skynet. The reason the Terminator wants to kill Sarah is that Sarah will one day have a son, and that son will eventually lead the human race to retake the Earth from the machines. As a last, desperate gambit to reverse its defeat, Skynet used an experimental time displacement device to send the Terminator back to the 1980’s on a mission to erase John Connor from the timestream by killing his mother before he was even conceived. Sarah is pretty sure Reese is out of his mind, but he’s obviously right about two things— that huge guy is indeed out to kill her, and he certainly does exhibit degrees of strength and resilience in the face of grievous injury which no man ought to possess. The final factor deciding Sarah in favor of trusting the seemingly unhinged Reese is what happens at the police station after Traxler and his men catch up to them and arrest the supposed time-traveler. The Terminator comes looking for her even there, and true to Reese’s word, 30 armed cops are barely enough to slow it down. Reese manages to get Sarah away in the confusion of the battle, but he frankly admits that he doesn’t like his chances of destroying a Terminator with the weapons available to a pair of fugitives in 1984.

So what exactly do I mean by the phrase, “big, smart action movie?” Well, let’s begin with “big”— it is, after all, the easy part. The modern school of Hollywood action movie, with its emphasis on breathless pacing, huge explosions, and choreographed gunplay, has its most obvious roots in the 80’s. There were the exploding bamboo movies on the model of Missing in Action. There were the vigilante and hero cop films, which, though they began in the 1970’s as a cathartic response to skyrocketing crime rates, didn’t really hit their peak of popularity and spectacle until the following decade. Then, of course, there was the curious subset of films in which a renegade retiree from the Special Forces uses his military and covert operations training to lash out at injustice, like Billy Jack with an M-60 machine gun. Taken together, what these trends established was the principle that action movies could and should be every bit as spectacularly violent— and as morally relativistic— as horror films had become since the late 1960’s. James Cameron’s innovation with The Terminator was to crossbreed the descendants of Death Wish and First Blood with science fiction, beginning a lineage that would include some of the most wildly popular movies of the next twenty years— not the least of which would be Cameron’s own Aliens and Terminator 2: Judgment Day. He did a top-notch job of orchestrating the mayhem, too. Unlike many films which are built around a single, continuous chase between an implacable villain and heroes who are ill-equipped to face him in a standup fight, The Terminator never becomes monotonous. Cameron took great care to vary the character of the numerous motor vehicle chases, for one thing: different scenery, different numbers of participants, different combinations of vehicle capabilities (police cruiser vs. V-8 land yacht, pickup truck vs. motorcycle, pedestrians vs. tanker rig). The even more frequent gun battles get the same sort of treatment, with the result that The Terminator rarely seems to repeat itself, despite a villain who has exactly one purpose in life and knows exactly one way to go about achieving it.

As for the “smart,” it mostly makes its appearance in the handling of The Terminator’s sci-fi elements. Time travel stories are always an extremely tricky business, but Cameron and co-scripter Gale Ann Hurd did a fantastic job here. For once, we have a story that uses the inevitable paradoxes to its advantage, suggesting that, contrary to the message from John Connor which Reese delivers to Sarah, the future is already set, and that efforts on the part of time-travelers to change it will succeed only in bringing the predestined events about through unexpected means. In the end, we see that it is precisely Skynet’s attempt to assassinate Sarah Connor which sets in motion the chain of events that leads to the computer’s destruction in the early 2030’s. Sarah would never have become the resourceful, indomitable woman who survives global nuclear war and then raises her son to be Skynet’s deadliest enemy were it not for her own life-or-death struggle against the Terminator during her youth. Meanwhile, John Connor’s decision to send Kyle Reese in pursuit of the Terminator winds up causing his own existence in an example of temporal circularity which is mind-bending in its elegance. (Furthermore, there is every indication that Connor knew Reese was destined to be his father, and subtly, deliberately manipulated him into volunteering for the virtually suicidal trans-temporal rescue mission!)

And as with the symphony of violence, Cameron succeeds masterfully at putting across both his fascinating ideas about the nature of time and human agency, and the complicated back-story regarding Skynet, the war, and what came afterward. Astonishingly, Cameron crams most of the exposition into a pair of long monologues from Reese without making them seem either contrived or boring. Sarah, after all, is going to want to know how and why a 23-year-old LA diner waitress has suddenly become the object of a battle to the death between two heavily armed men she’s never even seen before, while a lengthy interrogation about the mechanics of time travel is exactly what we’d expect from police psychologist Paul Silberman (Earl Boen, from Battle Beyond the Stars and Stewardess School) after Kyle’s arrest. Cameron even succeeds in disguising what might in other hands have been a glaring plot contrivance. One of the things that distinguishes The Terminator from most other time-travel movies is the fact that neither Reese nor the Terminator brings any advanced weaponry or equipment with him from the future. Obviously this was an attempt on Cameron’s part to raise the stakes both by making the Terminator that much harder to destroy and by allowing Reese no way to offer any tangible evidence that he is who he says he is, either to Sarah or to the authorities. The trouble, of course, is that this is very difficult to justify in plot terms, and it would be practically impossible to give a defensible explanation for the justification that Cameron adopted— that the time displacement equipment works only on living things, and that the Terminator itself is able to make the jump only because its “hyper-alloy combat chassis” (which, when we finally see it, resembles nothing so much as a robotic version of Ray Harryhausesn’s famous fencing skeletons) is completely encased by culture-grown human flesh. But because Reese is a soldier and not a scientist, there’s no reason why he would understand the intricacies of the time machine any more than the average man today understands what really goes on inside his computer. When Silberman asks him why only the living can be sent through time, there is no answer Reese can give the head-shrinker beyond a frustrated, “I didn’t build the fucking thing!” To some extent, this is a cop-out on Cameron’s part, but it’s a cop-out that works.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact