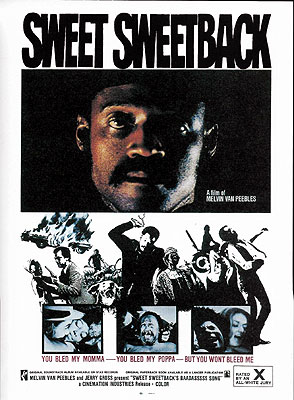

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song/Sweet Sweetback (1971) ***

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song/Sweet Sweetback (1971) ***

There were always two faces to blaxploitation. On the one side were movies like Shaft and Superfly, in which race was largely incidental except in the context of marketing. Their stories could be told with white or Asian or Latino characters instead, and only a few surface details would have to change. Hell, sometimes— like in Black Caesar or Blacula— the tales already had been told from a white perspective, and the explicit point was to give black audiences a version of their own. But then there were others so deeply rooted some aspect of black culture, lifestyles, or historical experience that it becomes absurd to imagine their stories being told from any other point of view. These movies (to borrow a turn of phrase from Juniper, who borrowed it in turn from that greatest of 21st-century sages, Some Guy on the Internet) don’t just “happen” to be black— they’re black on purpose. Naturally, there tends to be a lot of overlap between being black on purpose and having a sociopolitical axe to grind, but there are other ways to go about it, too. Ganja and Hess, for example, is black on purpose because of the specifically black interpretation of Christianity that informs it. Dolemite is black on purpose because of all the time Rudy Ray Moore spends up onstage doing something that white culture doesn’t even have a name for. (Is he a standup comedian? A storyteller? A rapper? Yes to all, and also none of the above.) You could even make a case that Sugar Hill is black on purpose, thanks to its atypically thoughtful and respectful approach to Voodoo lore, its explicit equation of undeath with slavery, and Don Pedro Colley’s portrayal of Baron Samedi. And then of course there’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, the original black-on-purpose blaxploitation movie, which is intensely political, but rarely in ways that Serious Intellectualstm will be prepared to recognize.

Sweet Sweetback (Melvin Van Peebles, later of Jaws: The Revenge and Fist of the North Star) was an orphan, adopted as a baby by prostitutes and raised by their pimp, Beetle (Simon Chuckchester), to be the brothel’s star performer in live sex shows. One night while Sweetback is doing his thing, a couple of white police detectives (I’m not sure who plays these two specifically, but pretty much every middle-aged Italian-American character actor who ever played a racist cop in a blaxploitation movie is in this one somewhere, playing a racist cop) come in with a proposition for Beetle. Their captain is riding their asses about some unsolved cases, so they’d like to borrow Sweetback for a little while. They’ll arrest him to make it look like they’re doing their jobs, the charges against him will get dropped for lack of evidence, and everyone will get on with their lives like nothing ever happened, right? Beetle agrees, and Sweetback goes quietly, but the situation changes when the cops get a call on their radio en route to the precinct. Apparently a black political activist called Mu-Mu (Herbert Scales) is getting a crowd riled up, and police on the scene think a riot is in the offing. Sweetback’s hosts detour to the site of the commotion, and take Mu-Mu into custody. Then they take him someplace nice and remote to kick the living shit out of him. Sweetback watches impassively for a while, but then makes a decision that nothing in his behavior so far would predict. He enters the fray and beats the detectives comatose, wielding their own handcuffs as an improvised set of brass knuckles.

Needless to say, the Los Angeles Commissioner of Police (John Dullaghan, from The Thing with Two Heads and Sex and the Single Vampire) is not pleased with any of these developments. And the one lead the LAPD has is that the stricken cops were last seen on the way to Beetle’s whorehouse. So maybe Sweetback shouldn’t be surprised, when he returns home for help, to find that the police got there first, and that Beetle has already agreed to cooperate in laying a trap for him. Still, it has to sting being sold out by the closest thing to a father he’s ever known. When Sweetback completes his second of many escapes from police custody a few minutes later, he tries his luck with an old girlfriend (Tenement’s Retta Hughes). She’s happy to see him, and she certainly sympathizes with his plight, but harboring a fugitive means way more danger than she’s willing to accept into her life right now. Next, Sweetback goes to a church he knows where the minister (West Gale, who played essentially the same role again in Dolemite and Avenging Disco Godfather) is a militant black nationalist. Surely he’ll be willing to offer sanctuary to a wanted brother, right? Nope. The city authorities have it in for the preacher and his church as it is, and protecting Sweetback would mean jeopardizing the shelter for drug addicts, unwed mothers, and the like operating out of the church’s attic. In the end, the most effective aid Sweetback is able to secure comes from a fellow vice-trader, the owner of a gambling den where LA’s petty criminals go in the hope of multiplying some of their ill-gotten gains. At first Sweetback tries to finagle enough money to buy a plane, train, or bus ticket out of the city, but in the end he settles for a ride into the hills. Along the way, Sweetback spots Mu-Mu on a street corner, and convinces him to come along. Obviously one fugitive can’t plausibly shelter another, but maybe they can watch each other’s backs until they can find someplace safe.

There’s a complex of abandoned and half-ruined buildings not far from where Sweetback and Mu-Mu get dropped off, so at least it looks like they’ll have a secure place to spend the night. What the fugitives don’t realize is that those ruins are already being squatted by a chapter of Hell’s Angels. The bikers don’t like uninvited guests, especially ones without enough money to be worth shaking down. Eventually the Angels decide that Sweetback and Mu-Mu can stay if and only if one of them can best their leader in a duel. The chapter president turns out to be a towering Valkyrie of a woman alternately called Red or Big Sadie (Sonja Dunson, from Nightmare Circus and Beautiful People). Fighting her bare-handed is a bad idea, because she’s strong enough to deadlift her hog. Switchblades are an even worse choice, since Red throws knives like Danny Trejo’s assassin in Desperado. With the bikers all impatiently badgering him to choose the form of the contest, Sweetback figures he might as well make it something he knows he’s good at. “Fucking,” he spits laconically into the silence that falls when the bikers realize he’s made up his mind. Sweetback is indeed deemed the winner, and two of Sadie’s minions show him and Mu-Mu to more comfortable accommodations than those they’d already found. At this point, there’s good news and bad news for the fugitives. The good news is, Sadie calls in a favor from the East Bay Dragons to have one of their men (John Amos, of Two Evil Eyes and The Beastmaster) come pick them up. The bad news is, not all of Red’s followers are on the same page as her, especially when it comes to doing favors for black dudes. Two of the Angels go behind Big Sadie’s back and tip off the police. By the time the Dragon arrives, two cops are dead and Mu-Mu is badly wounded. Sweetback figures Mu-Mu needs the rescue more than he does at this point, and sends him off on the back of the biker’s hog while he himself begins the long march to the Mexican border alone.

The commissioner is driven nearly crazy by his men’s inability to apprehend Sweetback, and he commits ever more resources to the task. The police response becomes more and more desperate, and also more and more obviously inexcusable in its excesses. As the manhunt spreads through the city’s black community, so too does unwillingness to cooperate with it in any way. Even Beetle has grown a spine by the next time the police put pressure on him, enduring terrible torture rather than telling them anything they could possibly use. Meanwhile, rebels of other sorts start coming to Sweetback’s assistance in small but vital ways. The cops gain ground steadily, but they remain always at least one step behind their quarry. Nevertheless, this is a movie that seems tailor-made for a 70’s bummer ending, don’t you think? Incredibly, though, that isn’t the kind of mythmaking that Van Peebles has in mind. Instead, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song concludes with its title character still at large, and a promise that he will return from exile one day “to collect some dues.”

The production of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song was a tale worthy of being filmed itself— a point well appreciated by its principal creator’s son, who did just that as Baadasssss! 32 years later. Melvin Van Peebles had been trying to get a movie about the black experience made in Hollywood throughout the whole back half of the 1960’s, but the closest the studios would let him come was to make movies about white perceptions of and reactions to that experience. Perhaps even more vexing, the men who controlled the industry in those days seemed not even to understand the difference. So as the 70’s dawned, Van Peebles took matters into his own hands— although he never guessed at first just how full those hands would end up being. Obviously he would write the script for his pet project, because the whole thing was his idea in the first place. Obviously he’d direct, too, because that was the only way to be sure the finished product would more than incidentally resemble his vision. And the overriding lesson of his years in the movie business thus far was that he’d have to produce as well; otherwise, he’d spend more time fighting with the producers than making the damn film, just like always. Van Peebles hadn’t planned on playing the lead role himself, however. That fourth hat was forced onto his head when he couldn’t find anyone else who wanted the part, between the picture’s lurid subject matter and Sweet Sweetback’s virtual absence of dialogue. As for Van Peebles writing the score, that was purely a matter of money— as in, there wasn’t any when the time came to fill in the gaps between the songs contributed by a pre-stardom Earth, Wind, and Fire. Lack of funding was such a persistent problem, in fact, that production could proceed only in fits and starts, as if Van Peebles had woken up one morning in the body of Al Adamson. That’s part of the reason for the film’s drastically episodic structure. Van Peebles knew he couldn’t count on any given performer keeping the same hairstyle, beard, or moustache from one scene’s shooting to the next, so he rigged it so that only two of them (himself and Simon Chuckchester) couldn’t be dispensed with after two or three days’ work at the outside.

More than anything, Sweet Sweetback’s production woes forced Van Peebles to develop a talent for turning adversity to his advantage. Two anecdotes should suffice to illustrate the point. First, there was the time Van Peebles wrung a financing windfall out of venereal disease. It isn’t obvious in the completed film, but most of the sex scenes in Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song were unsimulated. One of the actresses whom Van Peebles fucked had gonorrhea, and she passed it along to him. A bummer to be sure, but Van Peebles shrewdly realized that because he had gotten sick as a direct consequence of his working conditions, he had the basis for an open-and-shut, albeit extremely novel, worker’s compensation claim with the Directors’ Guild of America. The settlement he got from the union paid for the next spasm of shooting, while he presumably paid for the penicillin out of his own pocket. Then there was the incredible inadvertent favor which the MPAA ratings board did Van Peebles by slapping Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song with an X. Given both the film’s aims and its intended audience, could there possibly have been a more potent marketing angle than “Rated X by an All-White Jury?”

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song landed smack in the middle of the sweet spot to piss off everybody. I’ve already mentioned what the ratings board thought of it, and the only distributor Van Peebles could attract the first time around was the bottom-feeding Cinemation. (New World Pictures handled the theatrical reissue in 1974, however, after the movie had proven itself profitable. Once again, may whatever gods there be bless Roger Corman and his mercenary little heart.) Exhibitors in white neighborhoods mostly wanted nothing to do with any film so openly inflammatory, effectively shutting it out of a lot of markets. Mainstream critics, on the whole, found it baffling and/or tasteless. And black intellectuals of both the “respectable” and the neo-Marxist persuasions scorned it for wallowing in racist stereotypes, and for reducing black liberation to a matter of mere personal revenge. My favorite snide critical dismissal came from Lerone Bennett, who wrote in Ebony, “it is necessary to say frankly that nobody ever fucked his way to freedom… If fucking freed, black people would have celebrated the millennium 400 years ago.” One major public figure who did put his weight behind Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song was Black Panther Party founder Huey Long. His newsletter, The Black Panther, published a whole issue on the film, and he directed all party members to go see it. Indeed, where it was practical to do so, the Black Panthers organized neighborhood excursions to theaters where it was playing, in much the same way as Evangelical church groups would one day bus congregations out to the mall to see The Passion of the Christ.

What Newton got that eluded the likes of Lerone Bennett was that Van Peebles was offering not a program for black revolution, but a fable of it. That’s why it’s necessary that Sweetback is everything white racists of the day most feverishly imagined black men to be: a jobless, fatherless, violent, uneducated sex machine, whose only associates are criminals of one kind or another. His characterization is designed to turn those hateful stereotypes against their propagators by showing them as a potential source of strength for blacks whose racial consciousness has been awakened. And in any case, it’s clear enough that Van Peebles understood that the real work of black liberation was never going to proceed at all like what this movie portrays. The key scene here is the rescue from the Hell’s Angels hideout. The rider from the East Bay Dragons announces that he’s come for Sweet Sweetback, but Sweetback himself insists that the Dragon rescue Mu-Mu instead: “He’s our future, bre’er— take him.” That is, the real road forward involves boring, unglamorous, uncinematic things like giving speeches, holding rallies, publishing agitprop, and running for public office. Van Peebles’s fantasies of righteous outlawry are in the end nothing but fantasies. At the same time, though, if you doubt the power of fable, just ask a Lakota or a Paiute how the myths of the Wild West have impacted their lives.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact