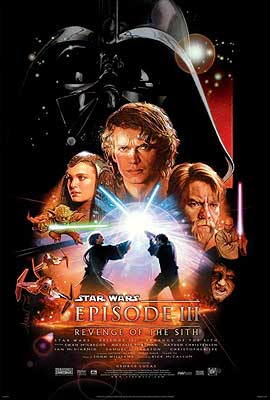

Star Wars, Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005) **

Star Wars, Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005) **

Once again, the conventional wisdom more or less has the right of it with the Star Wars prequels. I’d heard from just about everybody with an opinion on the subject that Star Wars, Episode III: Revenge of the Sith was the best of a sorry lot, with assessments ranging from “sucks the least” to “surprisingly okay,” and that’s indeed what I found when I finally watched Revenge of the Sith for myself. Sometimes, though, a just-barely-adequate movie can be more disappointing than a forthrightly lousy one, and this is a case in point. An obvious last-ditch attempt to right the course of the second trilogy and to redeem the prequel enterprise as a whole, Episode III comes achingly close to achieving the first of those aims. It addresses many of the most common complaints with the preceding films, and even manages to fix a few things that I’d assumed were broken beyond hope of repair. The second aim was always out of reach, however. There were just too many preexisting messes to clean up, too many bad ideas baked into the premise for this final installment to do more than to mitigate its predecessors’ failures.

We begin with a sequence that should have been the climax to Attack of the Clones. Under the leadership of Jedi Master-turned-Sith Lord Count Dooku— aka Darth Tyrannus (and played by Christopher Lee, whatever you want to call him)— the Separatist Alliance has brought the Galactic Republic to the brink of disintegration. General Grievous (voiced by Matthew Wood), the most formidable of the Alliance commanders, has laid siege to the galactic capital planet of Coruscant with a powerful fleet. Furthermore, in a daring gambit, some of Grievous’s commandos have abducted Supreme Chancellor Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid), the leader of the Republic for all practical purposes, and the general is now holding him prisoner aboard his flagship. While a clone-manned unionist fleet engages Grievous’s armada in orbit around Coruscant, the Jedi Knights Obi Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor) and Anakin Skywalker (Hayden Christensen) launch a commando raid of their own to get the chancellor back. There’s an unpleasant surprise awaiting the Jedi in the cabin where Palpatine is being held, however. The chancellor is under guard by Count Dooku himself, and it did not go well for Obi Wan and Anakin when they tangled with him at the end of the preceding film. This time, though, Anakin is a bit less Leroy Jenkins in his approach to the problem, and he’s advanced significantly in both his strength in the force and the skill with which he employs his powers. This time, it’s Anakin who leaves Dooku in pieces— four of them, in point of fact— after which the Jedi complete Palpatine’s rescue in grand if rather tumultuous style.

In the wake of his hero’s welcome on Coruscant, Anakin receives momentous news on the personal front. His secret wife, Senator Padme Amidala (Natalie Portman), is pregnant! A pleasant prospect in and of itself, but a fraught one for a couple who aren’t even supposed to be involved with each other in the first place. Impending fatherhood carries yet another dimension of worry for Anakin, too, because soon after Padme tells him about the pregnancy, he begins having troubling dreams about her dying in childbirth. Given the tendency of Anakin’s subconscious to show him glimpses of the future, he naturally reacts to these nightmares even more strongly than their content alone would encourage. But when Anakin goes to Yoda (Frank Oz) with a details-light version of his concerns, the old Jedi master is less than helpful. Yoda counsels Anakin to let go his attachment to whomever his dreams foretell danger for, so that he might face that danger in a stance of clarity and tranquility.

Meanwhile, the government of the Republic and the Jedi Council are each occupied with their own overhanging threats. Darth Dracula may be no more, but General Grievous is more than capable of leading the separatists to victory in his stead. He simply must be eliminated if the Republic is to maintain its unity. As for the Council, their big worry is the secretive Sith Lord whose fingerprints they’re beginning to see all over everything that’s befallen the increasingly troubled galaxy over the past fifteen years or so. Indeed, the mere fact that all the councilmen together remain unable to detect the movements of their hidden enemy via the Force is ominous. And as if General Grievous and Darth Sidious weren’t trouble enough, the Senate and the Council are starting to cast suspicious eyes on each other. The senators, for their parts, haven’t forgotten that the Jedi Council was opposed to establishing the army that has kept the separatists from overwhelming the Republic, while Yoda and his fellow councilmen don’t like the way Chancellor Palpatine keeps accumulating more and more power in his office.

Anakin, the poor bastard, gets caught right in the middle of the developing internecine conflict. He’s grown very close to Palpatine since the end of the last movie, so when the chancellor decides he needs a set of eyes and ears on the Jedi Council, he pulls some strings to get Anakin installed there despite his youth and inexperience. The leading Jedi acquiesce, but they symbolically protest against the interference by refusing to grant Anakin the rank of Master that traditionally goes along with the position. And at the same time, Obi Wan approaches his former apprentice with a scheme to have him keep tabs on Palpatine. ‘Cause obviously the guy whose loyalties you want to divide is the guy you just publicly slighted…

None of that is to say, however, that the Jedi and the Senate can’t work together toward a common goal. For instance, Obi Wan doesn’t hesitate a moment to risk his ass by hunting down General Grievous. Kenobi’s cooperation on that front turns out to be a disaster in the making, though, because his mission takes him away from Coruscant at exactly the time when Anakin most needs a mentor more benign than Chancellor Palpatine— who we know is really the same person as Darth Sidious, even if the Jedi do not. Palpatine knows about Anakin and Padme, and his clairvoyance has even told him about the young Jedi’s dreams of his wife’s death. When Anakin confesses that the Council have asked him to spy on Palpatine, the chancellor tells him a story about a Sith Lord called Darth Plagueis, whose power was so vast that the only thing he feared was the prospect of losing it. On the surface, the point of the chancellor’s tale is to warn Anakin of the lengths to which powerful people— like, say, the Jedi Council— will go in order to remain powerful. But because one aspect of the power that Darth Plagueis feared to lose was mastery over death itself, the secret moral of the story is that the Dark Side of the Force grants boons that the Light Side cannot— and that it specifically grants boons which a death-haunted youth could really use.

That, in case it weren’t obvious, is the first move of Palpatine’s endgame. While Kenobi is off chasing Grievous and Anakin is wrestling with the temptations of the Dark Side, Darth Sidious instructs the remaining separatist leaders to assemble on a remote volcano-mining outpost called Mustafar. And in his guise as Palpatine, he lets Anakin know that he can offer the Dark Side instruction that the Jedi Order cannot. Naturally that’s as good as admitting to being Darth Sidious, and Anakin isn’t yet so thoroughly suborned that he won’t try to do what he’s been trained to think of as the right thing. But then number-two Jedi Mace Windu (Samuel L. Jackson) plays right into the chancellor’s hands by attempting to kill Palpatine when he won’t submit quietly to arrest. Anakin follows Windu to the chancellor’s office, arriving just in time to see the old man obviously getting the worst of his duel against the Jedi master, and Skywalker’s intervention creates an opening for Palpatine to sucker-punch Windu with a blast of Force lightning. With Windu dead, Anakin recognizes that he’s made his choice, whether he consciously intended to or not.

Sidious dubs his new apprentice Darth Vader, and lays out for him his role in the coming Sith revolution. First, Vader will go to the Jedi Temple with a detachment of clone soldiers, and kill everyone in the building— child trainees included. Then he will go to Mustafar to assassinate the assembled separatist leaders in their very safehouse. Meanwhile, Sidious as Palpatine will issue Special Order 66 to the clone troopers engaged in military operations all over the galaxy— the directive to kill all the Jedi Knights attached to their units. And when all that blood is shed at last, the chancellor will call an emergency meeting of the Senate to announce that he has foiled an attempted coup d’etat by the Jedi Order, and to proclaim himself emperor on the theory that the threats now arrayed against the galaxy can be countered only by untrammeled absolutism. A few Jedi escape the clone soldiers’ betrayal, however, and among them are Yoda and Obi Wan Kenobi. When they learn what’s happened, they decide that if Palpatine is going to accuse the Jedi of trying to overthrow him anyway, then they might as well really do it. Of course, we already know that their last desperate bid to forestall a galactic reign of evil is doomed to fail, don’t we? I mean, Kenobi won’t be hanging out on Tatooine a generation hence because the desert air is good for his emphysema…

If I had to sum up in one sentence why Revenge of the Sith comes closer to working than its predecessors, I’d say it was because sometime in the interval between Episodes II and III, George Lucas finally figured out what story he was telling. The Star Wars prequels form a tale of decline and fall: of the Republic, of Anakin Skywalker, of the Jedi Order— even of Count Dooku’s separatist movement when you really think about it. And central to that is the point that Anakin is not and cannot be the good guy here, however understandable his motives might be. Recognition of that truth alone is enough to give Revenge of the Sith a degree of coherency and meaning that neither The Phantom Menace nor Attack of the Clones ever attained. Combine it with a script that can sit still for ten fucking minutes without charging off after some shiny object and a cast that has finally gotten the hang of acting under the brutally unnatural conditions that Lucas imposed on the set, and you really start to have something. Indeed, there are a few occasions on which this movie manages to be downright good for an entire scene!

Such praise is pretty faint, I realize, but it’s more than either of the earlier Star Wars prequels deserved. And crucially, a couple of those fully successful scenes concern pivotal developments along Anakin’s road to the Dark Side. The conversation between him and Palpatine at the opera house, where the chancellor recounts the legend of Darth Plagueis, reveals in Hayden Christensen a capacity for depth and nuance that no one would ever suspect on the basis of his performance last time around, and is one of the few instances in which the arch-villain comes across convincingly as an evil mastermind. The dual subtexts of Palpatine’s tale are furthermore the smartest thing to surface in a Star Wars film since Luke’s dilemma in the Emperor’s throne room toward the end of Return of the Jedi. The later scene in the chancellor’s office, where Anakin puts all the pieces together at last, is a similarly solid effort. In these scenes and these scenes alone, Anakin seems properly conflicted instead of just angst-wanking, and we get a fleeting glimpse of the Star Wars prequels that might have been.

It’s both too little and too late, however. To see why, it’s necessary to look at the prequel trilogy as a whole— which seems appropriate anyway, since we haven’t really done that yet. Basically, Revenge of the Sith’s faults are inherited ones for the most part, or at any rate the cascading result of things that went wrong in its predecessors. Most obviously, the flipside to Lucas having found the through-line of the story at last is that he didn’t already do that two fucking movies ago! That wrecks the entire triptych, and it wounds Revenge of the Sith specifically by forcing it to rush through a process that should have been unfolding, gradually but noticeably, since “Star Wars… Episode I: The Phantom Menace” first crawled up the screen in 1999. We shouldn’t just now be introduced to the idea of Palpatine stepping in to be the mentor for Anakin that Obi Wan isn’t. We shouldn’t just now be considering Anakin’s fear of his loved ones’ deaths as the driving force of his personality. We shouldn’t just now be seeing Anakin’s resentment of the Jedi Council as something deeper, stronger, and more justified than the whining of a teenaged narcissist. Most of all, we shouldn’t just now be introducing Anakin to the Dark Side of the Force as a real thing that can affect his life and those of the people around him.

The disastrously long wait to launch the central theme of the trilogy is even more galling when you consider some of the things that the prequels have been at pains to include since their inception. Needless callbacks to the originals are surely the foremost example here. Much of the magic in the first Star Wars sprang from the impression it created of a living, breathing universe of tremendous size and complexity, and The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi were successful on the whole in maintaining that fiction. In the prequels, though, the Star Wars universe seems to keep getting smaller and smaller despite all the new planets, new species, and new institutions Lucas introduces, and those callbacks are the reason why. What are the odds that of all the Wookiees on Kashyyyk, Chewbacca is the one assigned to serve as Yoda’s bodyguard while he oversees the defense against the separatist invasion? What are the odds that of all the professional rat-bastards in the galaxy whom Darth Vader could have hired to track the Millennium Falcon after the evacuation of Hoth, he’d pick the son of the guy from whom the Army of the Republic was cloned? What are the odds that of all the R2-series astro-droids ever built, the same one would keep turning up at the center of every momentous thing to happen in the galaxy for 50 fucking years like some electronic Forrest Gump? And how in all nine of the Hells are we supposed to believe that Darth Vader built C-3PO… out of garbage… in his garage… when he was ten years old… because he thought his scullery maid mother needed a protocol droid?

Then, on a related note, we have these movies’ determination to answer— generally to the detriment of the series— questions nobody was asking, while simultaneously contradicting what little solid data the originals presented about the past. Take the Emperor’s face, for example. I guarantee you nobody ever saw the Emperor march down that gangplank for the first time in Return of the Jedi and thought, “Huh. I wonder how he got to be so ugly?” We all just assumed he looked like that because he was so old and so evil that he was effectively his own Portrait of Dorian Gray and moved on. And you know what? That was good enough. More than that, it was better than any explanation for the old bastard’s appearance that might have been offered. And it was way better than being told, as we are in Revenge of the Sith, that he accidentally turned himself into rancid cottage cheese when a blast of his Force lightning bounced off of Mace Windu’s light saber and hit him in the face— not least because it didn’t prompt us to ask why Force lightning never turns anybody else into rancid cottage cheese.

As for contradictions, try this on for size: “When I first met him, your father was already a great pilot. But I was amazed by how strongly the Force was with him. I took it upon myself to train him as a Jedi. I thought that I could instruct him just as well as Yoda. I was wrong.” That’s Obi Wan Kenobi in Return of the Jedi, owning up to his inglorious past with the man who became Darth Vader. Only that isn’t quite what happened, is it? As we now know, it was Qui Gon Jin who was amazed at Anakin’s affinity for the Force, and who enrolled him at the Jedi Temple in the face of Yoda’s misgivings. Obi Wan’s involvement had more to do with honoring the memory of his own slain mentor than it did with any assessment of Anakin’s abilities. And although the parameters of “when I first met him, your father was already a great pilot” might be stretched to include “when I first met him, your father was a little boy who won a pod race once,” I’m still calling bullshit on it. But so what? We already know Obi Wan’s a liar, right? Well then how about Leia? How about her remembering impressions of her mother, recalling her as “very beautiful” and “kind, but sad?” If, as we now see, Amidala lived exactly long enough after her twins were born to name each of them, how is it even remotely possible for Leia to have any recollections of her whatsoever? A newborn baby’s visual cortex isn’t even wired up yet! Granted, none of this stuff is terribly significant in the grand scheme of things, but the point is, it’s sloppy. It’s lazy. And unlike the original trilogy’s retcon revelations about the Skywalker family, the contradictions here don’t add anything to the story.

Another place where the prequel trilogy screws up big is in its treatment of Padme Amidala. She never comes into focus as a character, her motives and behavior never relate to each other in any intelligible way, and she spends almost literally the whole of Revenge of the Sith hanging around her apartment on Coruscant waiting to die of nothing in particular. She’s merely a prop in the story of Anakin’s downfall— but she can’t even do that right, because her place in that story makes no sense unless it’s about her downfall, too. It takes two to conduct a forbidden love affair, after all, and the girl who falls for Darth Vader, of all people, can’t plausibly be so squeaky clean herself. I’m not saying she has to be Lady MacBeth, but at the very least, she’s got to have the mother of all bad boy fixations. It wouldn’t have taken much to set it up. Say Amidala was a real queen, thrust onto the throne at fourteen because she’s the last scion of a dying dynasty, and not because the Constitution of Naboo is profoundly stupid and the voting populace more so. Say Anakin is already in his late teens when circumstance carries Padme to Tatooine, and that his lifestyle as a pod-racing juvenile delinquent appeals to her by contrast with the crushing weight of responsibility that she has to bear. Meanwhile, let Anakin see Padme as someone he can never be good enough to deserve, however hard he strives to win and/or keep her. Trap them from the get-go in a dynamic of inadvertently feeding each other’s most destructive impulses. And then, once the couple have brought themselves and each other to the brink of damnation, get Amidala pregnant and portray her pregnancy as something truly and concretely dangerous to her. Dark as fuck by the standards of previous Star Wars films, I grant you, but this is supposed to be the origin of Darth Vader here. If you’re not going dark, you’re doing it wrong.

That little off-the-cuff exercise in script-doctoring points to the most mystifying thing about the Star Wars prequels, the ease with which better versions of this story spring to mind. Crappy as it all turned out, there’s actually very little in these movies that’s inherently unworkable. One really careful round of top-to-bottom rewrites (followed by a dialogue-polishing pass from somebody other than Lucas) could have fixed everything not directly attributable to shitty casting or directorial technomania. This brings me back to the thesis of my Empire Strikes Back review, only from the opposite direction: by the prequel era, Lucas appears to have bought into the flimflam which he once used to keep 20th Century Fox’s executives and accountants off his back, forgetting that the ideas behind the original trilogy didn’t really spring fully formed from his creative genius. They had to be bent and carved and beaten and sawed and sanded into shape, and whole worlds had to be abandoned, repurposed, and replaced before those scripts were ready for shooting. There had to be people around who were prepared to tell Lucas, “No, that’s not going to work,” and Lucas had to be prepared to listen to them. Or to resurrect another of my past review theses, the prequels are what happened when Lucas decided that he was an auteur after all, and attempted to run his show accordingly.

Now let’s talk about the fuck-ups that Revenge of the Sith has all to itself, the blame unshared with any of its predecessors. Some I’ve already touched on, like Palpatine’s disfigurement and Amidala’s reduction to irrelevancy. Of the rest, the big ones all orbit around the paired climactic fights, Yoda against Palpatine and Obi Wan against Anakin. Yoda vs. Palpatine is a lot like the clash between Yoda and Count Dooku in Attack of the Clones, insofar as it pits an implausible sword-wielding bouncy ball against a mostly immobile old man, but the latter fight at least had in Christopher Lee someone who’d done enough physical acting in his prime that he still remembered how to sell it. Ian McDiarmid doesn’t acquit himself half so well. And beyond that, the whole battle is an egregiously heavy-handed metaphor. It takes place in the Senate chamber, you see, and Palpatine’s main tactic is to launch the delegation boxes at his foe by telekinesis. So he’s using the Senate as his weapon. Ugh. Meanwhile, on Mustafar, Hayden Christensen takes the critical moment of the entire trilogy out behind the woodshed and puts a bullet in its brain. When it really counts, when everything is riding on Christensen’s performance and he absolutely cannot afford to get it wrong in any way, the believable, mature-yet-insecure new Anakin vanishes as if by malign magic, and the snot-nosed adolescent ass-baby comes bawling back to take his place. It’s debatable, to be sure, what the correct note is to strive for during a scene where your character is on fire and attempting to rebuke the man who just cut all of his limbs off with a laser sword, but I think we can all agree that it shouldn’t sound like a spoiled high-schooler bitching out his dad for refusing to lend him the space car. Coming after that, not even the infamous Worst NOOOOOOOOOO Ever can find any more damage to inflict.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact