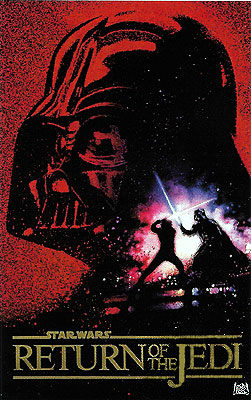

Return of the Jedi / Star Wars: Return of the Jedi / Star Wars, Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (1983) ***½

Return of the Jedi / Star Wars: Return of the Jedi / Star Wars, Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (1983) ***½

Those of you who’ve been reading 1000 Misspent Hours and Counting for a while should have figured out by now that I grade on a curve. This site casts too wide a net for me to do it any other way. Part of what that means is that I always try to determine what the makers of a particular film hoped to accomplish (beyond, obviously, making a bunch of money), and to bear those goals in mind as I evaluate their work. Given the subjective nature of the exercise, however, I can’t be dependably systematic about giving the question of intention vs. accomplishment the same weight every time, and for the most part I don’t really try. That matters with regard to Return of the Jedi, because whether I experience it as a good film or a great one depends entirely on how much I feel like caring about creator intent. You see, Return of the Jedi features a lot of what I would normally consider damning defects of structure and proportion, so that in and of itself, it’s by far the weakest of the original three Star Wars movies. But Return of the Jedi was never meant to be taken in and of itself. Rather, its purpose is to wrap up a trilogy, and when taken as a two-and-a-half-hour square-up reel, it is immensely satisfying. Furthermore, what makes Return of the Jedi so superb a capper to the series is the very stuff that harms it as a free-standing film.

The Emperor thinks— the entire Imperial high command thinks— the Death Star was a nice idea. But (not pointing any fingers here) it could’ve been done better. Maybe put a couple layers of armored grating in that thermal exhaust port to detonate a proton torpedo before it could reach the main reactor, that kind of thing. Next time, they’ll do the Death Star right, and go full regalia. Yeah, well “next time” is now. In orbit around the forest moon of Endor, a new, bigger, and more powerful Death Star is under construction. The Emperor (now played by Ian McDiarmid, from Dragonslayer and The Awakening) is dissatisfied with the rate of that construction, however, and he has sent Darth Vader (the body of David Prowse, the voice of James Earl Jones, and ultimately the face of Sebastian Shaw— all three of whom get their names in the credits this time) to light a fire under the builders’ asses. Literally, if necessary.

Elsewhere, a distinctly familiar scene is transpiring: the droids R2-D2 (Kenny Baker) and C-3PO (Anthony Daniels) trekking across the arid wastes of the desert planet Tatooine. This time, however, the robots have a clear destination in mind. They’re on their way to the palace of interstellar crime lord Jabba the Hutt to open negotiations between the gangster and their master, the Jedi Knight Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill). Well, he says he’s a Jedi, anyway; Jabba won’t be the only one to greet that claim with skepticism. The object of these negotiations will be to secure the release of Han Solo (Harrison Ford), the smuggler turned resistance fighter whose unpaid debts to Jabba earned him an open contract on his life two movies ago. This is the first time we’ve actually seen Jabba (unless we’re watching the bullshit “Special Edition” versions from the late 90’s [grumblegrumble]), and hot damn was it worth the wait. I don’t remember how I envisioned him prior to 1983, but I assure you that nobody was expecting a slug the size of a Buick, lounging on a giant concrete couch with half-naked humanoid slave girls chained to it.

Just like in the original Star Wars, R2-D2 is carrying a holographic recording, this one expressing Luke’s hope that he and Jabba can come to terms. As a token of his good will, Skywalker takes the rather astonishing step of transferring ownership of the two droids to the gangster. That comes as news to C-3PO, who greets the transaction with well justified dismay. His first job as Jabba’s interpreter is equally dismaying, as a masked bounty hunter arrives with a captive Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew). Take a moment to notice something, though. R2-D2, C-3PO, and Chewbacca make three of Han’s friends who are now under Jabba’s roof— and one of the soldiers guarding the crime lord’s throne room is really Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee Williams). Sound to you like Luke is up to something?

Indeed, it turns out that the bounty hunter who delivered Chewbacca is actually Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) in an extremely thorough disguise. On the night following her arrival, after everyone in the palace has gone to bed, Leia sneaks down to the throne room, where Han, still frozen into that block of carbonite, hangs against one of the walls like a macabre objet d’art. Being careful not to make any more noise than she has to, she sets the frame on the block to defrost, putting an end at last to Solo’s ordeal. Leia hasn’t been careful enough, however. Jabba and some of his minions are awake after all, and the next time we see the princess, she’s chained to the gangster’s couch in an outfit that ushered an entire generation of nerdy young boys into puberty. But that same morning, Jabba receives yet another visitor— Luke Skywalker himself, whose powers have grown formidable indeed since the time he got every square inch of his ass kicked by Darth Vader. Jabba doesn’t stand a chance.

That’s one bit of unfinished business taken care of. Next, Luke makes his long-delayed return to Dagobah to take whatever Jedi final exams he skipped out on in the middle of The Empire Strikes Back. To his surprise, Yoda (still voiced and puppeteered by Frank Oz) says there’s nothing left for him to be taught. And even if there were, Yoda’s health has taken a turn for the worse, and he’s no longer up to the task of training anyone. Instead, Luke and Yoda spend the latter’s final hours discussing Vader, and the truth or falsity of his claim to be the lad’s father. It’s no lie, which means that Luke will also be having it out with the ghost of Obi Wan Kenobi (one last appearance in the part by Alec Guinness) about that “Darth Vader betrayed and murdered your father” bullshit. Obi Wan’s justification is just as lame as you’d imagine. He does, however, spring on Luke a bombshell secret of his own, which is that Luke has a twin sister whom Yoda somehow contrived to hide in plain sight from Vader, the Emperor, and everybody else. How plain are we talking about here? Would you believe she’s Princess Leia? Strangely, Luke does— without even feeling suddenly icky about the love triangle he’d been forming with Leia and Han since they all first met up in that cell block on the original Death Star. When Luke leaves Dagobah for the last time, it’s not only with a new understanding of his place in the cast, but also with a new sense of purpose. If they truly are father and son, then the best thing Luke can do as a fully fledged Jedi Knight is to seek out Vader and dig out of him whatever still remains of Anakin Skywalker— to do with Vader the opposite of what the Emperor hopes Vader will do with Luke.

For the Rebel Alliance as a whole, though, the top priority is understandably to destroy the new Death Star before it can be completed. The Rebels have put together a powerful fleet under the command of the squid-like Admiral Akbar (a composite performance by puppeteer Tim Rose and voice actor Erik Bauersfeld), but it won’t do them any good so long as the Death Star is protected by its energy shield, projected into space from an outpost on the surface of Endor. Therefore, the plan is for Luke, Han, and Leia to sneak a commando team down to the moon in a stolen Imperial shuttle, to capture the generating station, and to shut down the shield. Then Lando Calrissian will lead a small force of single-seat fighters into the exposed guts of the unfinished battle station to hit its main reactor, while Ackbar and his armada keep the Imperial Starfleet from coming to the Death Star’s rescue. There are just a few things that the Rebels haven’t figured on. First, Endor is home to a race of xenophobic stone-age teddy bears called Ewoks, whose presence rather complicates the commando team’s mission. Second, Darth Vader can sense at orbital range the ripples his son produces in the Force, so Skywalker is endangering the mission simply by taking part in it. (On the other hand, getting noticed and captured by Vader would be something of a boon to Luke’s personal mission of turning his old man away from the Dark Side.) And third, the Emperor’s dark Jedi powers exceed even Vader’s, and his clairvoyance is such that there’s basically no surprising him by ordinary means. He knows the Rebels are coming; the Imperial fleet is already in place, hiding on the far side of the moon from the Death Star; and work on the battle station’s combat systems has been artificially accelerated, so that it can fight at full power even though it’ll be months yet before its structure is completed. As Ackbar will famously remark before long, it’s a trap.

There are two common lines of complaint among fans who were disappointed by Return of the Jedi. First, there are those who grumble that it panders to the juvenile audience, positioning itself as a kids’ movie, rather than a film for general audiences that might have special appeal for children. Then there are the folks who object that Return of the Jedi is an absolute mess from the perspective of narrative construction. Neither gripe is unfair. This movie has a teddy bear planet, for fuck’s sake, to say nothing of two musical numbers, the most harmlessly incompetent Imperial storm troopers yet, and a pronounced bent toward an astutely childish brand of black humor (witness Jabba’s torture chamber for droids, the weeping Rancor trainer, and the Sarlac’s tendency to belch whenever someone falls into its giant, immobile maw). The revelation of Darth Vader’s true face toward the end of the film reflects the new sensibility, too, seeming calibrated to assure us that he wasn’t really so scary after all. Even at the age of nine, I thought that was a step too far; a figure like Vader should inspire dread even in redemption. Meanwhile, on the story architecture front, Return of the Jedi spends the first third of its running time tying off its predecessors’ loose ends, drops in a low-stakes interlude introducing a whole new cast of supporting characters just before the halfway point, and devotes more than an hour to three concurrent climaxes: the Ewok uprising on Endor, the space battle in and around the Death Star, and the clash of wills and light sabers in the Emperor’s throne room that will decide the fates of Luke and Anakin Skywalker. What the hell kind of plot balance is that?

Both sets of objections miss something important, however, which is that the position of the Star Wars franchise changed dramatically between 1977 and 1983; the kiddification and lopsidedness of Return of the Jedi are each defensible as responses to the new state of affairs. When the original Star Wars arrived on the scene, it was impossible to be certain who its audience was really going to be. In fact, some people at 20th Century Fox were never fully convinced that it would find one at all. But in the 80’s, it was obvious not only that any Star Wars movie was going to sell millions upon millions of tickets, but that the core audience for the series was actually the children of the people at whom the first film was initially pitched. Star Wars mania may have been one of the last nigh-universal pop culture phenomena, but for the kids of the late 70’s and early 80’s, it was even more than that. We wanted to be these people; we wanted to live in these places; to us, the universe that George Lucas and his collaborators had invented was almost as real as the one we had been born into. So by adjusting the series to the tastes of his youngest fans, Lucas was doing no more than to give them their due.

Besides, it isn’t as though Return of the Jedi is short on appeal for older viewers. One look at Carrie Fisher’s celebrated brass bikini should clue you in to that. More substantially, the central Luke-Vader-Emperor triangle has nuances that went entirely over my head when I saw this movie for the first time at the age of nine. By the time Vader brings Luke before the Emperor to witness what the latter fully expects to be the end of the Rebel Alliance, this series has never once resolved a conflict between heroes and villains without resorting to violence. But in the Emperor’s throne room, as battle rages across both the surface of Endor and the moon’s orbital space, Luke faces a situation in which to fight is to lose, regardless of who comes out on top. He might beat Vader— he might even beat the Emperor— but in doing so, he would become one of them, a perversion of the Force rather than the Jedi Knight he claims to be. Furthermore, Vader and the Emperor are each willing to sacrifice themselves if that’s what it takes to make certain Luke succumbs to the corruption of rage and hate. In its way, the rematch between Luke and his father is the most sophisticated development in the series so far. As Luke gains the upper hand, unleashing his full Jedi power and skill in a fight not just for his own life and soul, but for Leia’s as well, each blow he lands brings him closer to damnation and the Emperor closer to victory. For that matter, the death of Jabba the Hutt is pretty smartly handled, too, hinging as it does upon the inversion or avoidance of practically every heroic fantasy trope that might seem applicable to the situation. A lot of the kids watching this movie for the Ewoks would never even notice what Lucas, co-writer Lawrence Kasdan, and director Richard Marquand had done there.

The other important point about the rising fortunes of the Star Wars franchise is that people who know they’re making three movies almost invariably behave differently from people who assume they’re making only one. The original Star Wars left plenty of options open for continuation and expansion, but it was reasonably complete in itself. To write it any other way would have been madness— as Ralph Bakshi would learn the hard way when his The Lord of the Rings bombed a year later, condemning that version of the tale to remain forever unfinished. When Lucas got the go-ahead for two sequels (plus a vague expression of interest in three to six more if the things kept making money), it was effectively an encouragement to think much bigger, and to play a much longer game. The Empire Strikes Back was freed to set things up without resolving them, provided that Return of the Jedi resolved them instead. So whatever else the third installment did, its primary responsibility would be to cash the checks written by its predecessor. That’s exactly what Return of the Jedi does, and the emphasis on cancelling those outstanding debts explains why it’s put together so strangely. It reveals Jabba, rescues Han, settles the issue of Luke’s interrupted training, explains that baffling line about Skywalker not being the last hope for the Jedi order, and carries the plot to convert Luke to the Dark Side to a rich and resonant conclusion. That doesn’t leave a lot of room for new business, especially if that new business is going to include the final overthrow of the Emperor. Consequently, it was actually a smart move to invest the bulk of this movie’s time and energy in the wrap-up the series required, even if that meant Return of the Jedi would feel more like a succession of tangentially related third acts than a complete work in its own right.

They are, after all, an exceedingly impressive bunch of third acts. The Tatooine segment raises the ante on the Cantina Café with a vision of interplanetary cosmopolitanism exceeding anything ever attempted before. It gives Leia a chance to establish her Action Girl bona fides, while simultaneously showing us for the first time what a Jedi Knight in the fullness of his powers can do. And its “Skywalker’s Seven” caper approach fully integrates Lando into the ensemble while introducing a new set of genre tricks to the series. The fighting on Endor extends Star Wars’ genre reach in still another direction, bringing a bit of Lawrence of Arabia into the mix. The orbital faceoff between the Rebel and Imperial fleets remains the standard by which I judge live-action space battles even 32 years later. And there is simply no conclusion to which this saga could come that would surpass the emotional power and psychological aptness of what happens aboard the Death Star between Luke, his father, and the human monster who drove them apart. Not only will I happily accept Ewoks in exchange for all that, but I’ll happily accept singing Ewoks. Yub fucking nub, y’all.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact