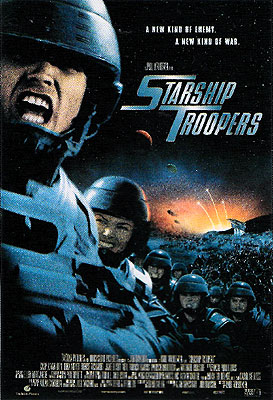

Starship Troopers (1997) Ĺ

Starship Troopers (1997) Ĺ

Itís amazing how quickly things you say can come back to haunt you. Just a couple of weeks ago, I wrote in my review of The Boogens that ďIíll gladly endure movies that suck a caribouís assó even by my dazzlingly low standardsó if it means Iíll get to see a cool monster.Ē It turns out, though, that even I have my limits. With Starship Troopers, Paul Verhoven and Edward Neumeier have found them.

Iím not a Robert Heinlein fan, and I confess to never having read the novel on which this septic tank of a movie is based. Thus, Iím going to keep my nose out of the ongoing arguments over whether or not Verhoven missed the point of Heinleinís book; Iím not qualified to say what Heinleinís point was in the first place. And in any event, thereís something far more interesting going on in Starship Troopersó Verhoven actually seems to have missed the point of his own movie! This, after all, is a sci-fi war film, in which the human race is forced to fight for survival against a race of insect-like aliens called (imaginatively enough) the Arachnids. Its main characters are a boy and a girl who graduate from high school, enlist in the military, and almost immediately find themselves on the front lines of this ghastly conflict. So why, then, does Starship Troopers spend the vast bulk of its 129-minute running time aping the prime-time soap operas from which so many of its cast members were drawn, shoehorning the action that we are really here to see into its final incoherent half hour?

John Rico (Casper Van Dien, from Modern Vampires and Beastmaster III: The Eye of Braxus), Carmen Ibanez (Valentineís Denise Richards), and Carl Jenkins (Neil Patrick Harris) are three teenage friends from Buenos Aires. The time is many centuries in the future, and the Earth has been unified under the rule of a single government, the political character of which is somewhere between ancient Sparta and Mussoliniís Italy. Society is strictly regimented, the people are kept docile by material convenience, and political leadership is the exclusive province of the citizenry, an elite minority of the population who earn their rights through military service. Carl and Carmen both seek citizenship, and thus plan to enlist in the Federal Service after graduationó Carmen in the fleet, and Carl in the intelligence corps, where his psychic powers will put him in high demand. John has been accepted by Harvard, but because he is in love with Carmen, he intends to ditch college and join the Mobile Infantry (his academic performance is too weak to get him into the Fleet Academy with his girlfriend, which suggests that Harvard has relaxed its standards slightly over the centuries), even if it means sacrificing his relationship with his parents, both of whom are civilians, and strongly disapprove of the military.

But there are complications to this central dynamic, as there must be in any soap opera. John is a football player, and his quarterback, Dizzy Flores (Dina Meyer, of Bats and Johnny Mnemonic), has the hots for him. Meanwhile, a player from a rival team, named Zander Barcalow (Stigmataís Patrick Muldoon, whose previous experience in the casts of ďMelrose PlaceĒ and ďDays of Our LivesĒ is surely not coincidental), has been macking on Carmen, not entirely without success. And because both Dizzy and Zander have signed up, too (Dizzy in the Mobile Infantry, Zander in the fleet), they will both be around to complicate things even after the school year ends.

I hope you like this plot, because itís all weíre going to get for the next hour and a half or so. Amid training sessions and fistfights and coed shower scenes and video love letters, John and Carmen break up and a natural enmity forms between John and Zander that neatly parallels the traditional rivalry between their respective branches of the Federal Service. Carmen moves steadily forward in her career, and develops a reputation as one of the finest helmsmen in the fleet. Johnís career path isnít so smooth, though he does make squad leader before heís even out of basic training. He almost blows everything, though, when one of his teammates is killed in a routine training exercise. In fact, heís on his way to his resignation when he hears that the Arachnids (whom humans have always assumed to be little more than animals) have somehow found a way to use the asteroids that litter their star system as interplanetary bombardment weapons. One of those asteroids has just smacked into the Earth, destroying Buenos Aires, and with it everything that any of the central characters hold dear. And more to the point, it also means that humanity is now at war with the Arachnids.

What is does not mean, unfortunately, is that the soap opera portion of the evening has come to an end. Tantalizing hints of real action begin surfacing at this point, but the dipshit love story is still in the movieís driverís seat, and will remain there for quite some time. Indeed, even though it is far more important overall, the revelation that the Arachnids arenít just smarter than we realized, but are in fact winning the war is passed over elliptically, as though it were a mere subplot. All Verhoven seems to care about it Dizzyís ultimately successful quest to get into Ricoís pants. But eventually, Carmenís unit of the Fleet is assigned to drop Ricoís M.I. company on a planet called ďP,Ē which, contrary to all assurances from the government, turns out to be positively infested with Arachnids. Major characters drop one by one (including, frustratingly enough, Ricoís commanding lieutenant, who is played by Michael Ironside of Scanners, the only decent actor in this movie), and Rico is consistently promoted to take their places, until finally defeat becomes so obviously unavoidable that the fleet airlifts the soldiers off the planet.

They have to go back, though, because the stiffness of the Arachnidsí defense has convinced the intelligence corps that there is a ďbrain bugĒ on P. Carl, now an intelligence corps colonel, reenters the movie to take command of the operation to capture this thinking Arachnid. Ricoís unit is sent back down to the surface, while the destruction of Carmen and Zanderís ship forces them to land on P as well. The two helmsmen find themselves surrounded by Arachnids in short order, and are soon brought before the brain bug for interrogation, an operation which involves the creature (it resembles nothing so much as a six-ton clitoris) sucking their brains out through a straw-like appendage on its face. (You know, ripping off Attack of the Crab Monsters maybe isnít such a good idea.) Zander dies, but Carmen foils the creatureís plans by cutting off its proboscis with her boot knife before it can do the same to her. And just then, Ricoís men come to the rescue, rushing Carmen to safety and communicating the whereabouts of the brain bug to the rest of the army. The brain bug is captured, Carl discovers that he can, in fact, read its alien mind, and the credits roll at last, leaving the actual story completely unresolved.

The general consensus on the part of its defenders is that Starship Troopers is a satire on modern American militarism of the Gulf War variety, or on the propagandistic war movies of the 1940ís, or even on the Nazisí notorious propaganda machine. And for my part, Iím going to assume this to be true, on the grounds that the idea of a Dutch director growing up in the 40ís, only to film a ringing endorsement of fascist militarism 50 years later is too disturbing to contemplate. But the fact is that the only parts of Starship Troopers that play like a satire on anything are the surreal television clips that Verhoven scatters throughout the movie. This is the same technique he used earlier (to much greater effect, I might add) in RoboCop, and as was the case in that movie, the tone of these interjections is far too arch for them to be meant seriously. On the other hand, the rest of the film plays with such a completely straight face that there is little to suggest that it isnít serious. The problem, I think, is that the incompetent young actors who comprise the bulk of the cast are incapable of anything but the cardboard earnestness they display here. I suppose itís also possible, as some commentators have suggested, that the players werenít in on the joke, and were in fact led by their director to believe that Starship Troopers really was the paean to jingoism and sabre-rattling that their performances suggest. Iíve never been much of a believer in conspiracy theories, though, and if it looks like bad acting, sounds like bad acting, and moves like bad acting, Iím inclined to say itís probably just good old-fashioned bad acting. And the fact that Verhoven let his cast get away with this high school drama club-level crap lays a hefty parcel of blame at his feet too.

But let us not forget about screenwriter Edward Neumeier. His script is so heavily laden with foolishness and illogic, and so completely mishandles its few good points that the mere fact that it was used at all would have defied belief had Starship Troopers not been released in 1997. Iíve already voiced my disgust that the usual romantic subplot has been elevated here to the point that it largely displaces what supposedly is the main storyline. But even when the movie finally gets down to business, and remembers that itís supposed to be about an interstellar war, so little creative energy goes into the action that it offers no respite at all from the audienceís torment. For one thing, all of the bug battles are exactly the same. The Mobile Infantry lands; the Arachnids attack; a couple of major characters are dismembered, causing Rico to move up a rank; the defeated soldiers have their asses pulled out of the fire by the fleet. There is never any indication that anyone has learned anything about how to fight the Arachnids, never any variation in the tactics used by either side. And whatís more, despite the passage of centuries, the Mobile Infantry is actually less well equipped than the U.S. Army of 50 years ago. Not only do these soldiers lack the famous power armor of the novel, they are without tanks, armored personnel carriers, artillery fire support, or even squad heavy weapons like the M-60 machine gun or the old Browning Automatic Rifle. They never call in air strikes or fire support from the fleet, nor do they have anything on their side remotely comparable to the helicopter gunships of today. Indeed, the only weapons they have that are more powerful than their wholly ineffective assault rifles are nuclear hand grenades, which they naturally canít really use in a melee situation. Of course the Arachnids are going to stomp their asses every single time!!!! Even if you didnít already hate everyone in this movie for their relentless Melrose Placing, youíd still figure they deserve whatever they get for being so stupid as to take on an entire civilization of bullet-proof bugs with a combination of weapons and tactics that wouldnít have stood up to the mercenary team from Predator. Cool as the Arachnids are (and by the standards of CGI monsters, the bigger ones at least are fantastic), their eye-candy value is nowhere near enough to make up for the stupidity, incompetence, and tedium of Starship Troopers.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact