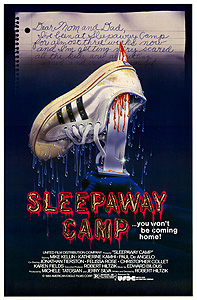

Sleepaway Camp/Nightmare Vacation (1983) ***

Sleepaway Camp/Nightmare Vacation (1983) ***

After all these years, it really shouldn’t surprise me anymore that 1980’s slasher movies have such a hard time getting a fair break, but once in a while I still get blindsided by a particularly egregious instance of knee-jerk anti-slasher bias. Now far be it from me to try to argue against the obvious and irrefutable point that the great majority of the things are stunningly unoriginal and fantastically stupid, or to contend that the standard slasher formula isn’t an inherently restrictive one which tends to bring the faults of bad filmmakers into the sharpest possible focus. But even when a movie comes along that strays beyond the usual limits, more often than not, it will be summarily dismissed as just more of the same anyway. Case in point: you will search long and hard before you uncover a review of Sleepaway Camp that doesn’t write it off as a slavish copy of Friday the 13th and call it a day. True, this is a movie about a killer at a summer camp, but to call it a simple Friday the 13th retread on those grounds alone is like saying that An American Werewolf in London rips off Werewolf of London because they both involve lycanthropy and are set in the capital of Great Britain. A close examination will reveal that Sleepaway Camp is in fact among the least formulaic of all the first-wave US slasher movies, and while certain elements of its story which were obviously included solely for the sake of shock value put a heavy strain on audience credulity, it is in most respects among the more realistic and believable entries in the genre as well.

We start off with an odd variation on the traditional groundwork-laying prologue. The credits play out over a pan across the property of the closed-down Camp Arawak, then the movie backtracks to reveal how the campground was forced out of business before jumping eight years into the future for the main action. In the flashback, a 30-ish man is out boating on a lake with his two young children. So far as the kids are concerned, the real excitement lies in watching some teenagers from Camp Arawak water-skiing, and their father brings the boat in just a little bit closer than is probably safe. Consequently, we know exactly what’s about to happen when the children manage to capsize their vessel just as the girl riding shotgun in the powerboat pulling the water-skier finally badgers the camp counselor pilot into letting her have the wheel for a bit. While the skier shrieks for her to slow down and a friend of the family from the overturned skiff shouts for them to get out of the way, the inexperienced girl running the powerboat drives the thing right over the father and one of the children, killing them both. With something like that happening right under the insufficiently watchful eye of a Camp Arawak counselor, it’s no wonder the place got closed down!

Eight years later, Angela (Felissa Rose, seen more recently in direct-to-video atrocities like Zombiegeddon and Nikos the Impaler), the sole survivor among the family from the prologue, is on the threshold of adolescence and living with her cousin, Ricky (Jonathan Tiersten), and her visibly crazy aunt, Martha (Desiree Gould). It’s the height of the summer, and Martha is about to pack the kids off to camp— at the newly reopened Camp Arawak, as a matter of fact. Angela doesn’t seem to be too happy about any of this, but Martha is sure she’ll have a wonderful time, and Ricky takes it upon himself to shield his cousin from as many of the coming travails as he can.

Now, as I believe I’ve mentioned before, I never went to summer camp when I was a kid. The elementary school I attended did, however, send all of its sixth-graders on a weeklong trip to a camp called Arlington Echo around the middle of each May, and when my turn came, the experience was more than enough to cure me of any desire I might have had to take part in that time-honored ritual of middle-class American childhood. In fact, to this day, I regard that trip as one of the five worst weeks of my life. I bring this up because summer camp as it is depicted in Sleepaway Camp would be exactly the way I remember my sixth-grade Arlington Echo excursion, if you took out all the stuff about the child-molesting chef and the revenge-driven serial killer. And yes, my ever-perceptive readers, the asocial, withdrawn, and almost entirely silent Angela is indeed my personal identification figure in that comparison. Upon arriving at Camp Arawak, Angela immediately becomes the favorite scapegoat not only of the popular and precociously pubescent Judy (Karen Fields), but of her cabin counselor, Meg (Katherine Kamhi, from Silent Madness), as well. The older boys led by the aggressively obnoxious Billy (Loris Sallahian) torment both her and Ricky at every opportunity, and camp owner Mel (Mike Kellin, of God Told Me To and The Boston Strangler) generally does little or nothing to stop them. Indeed, apart from Ricky himself and a couple of decent counselors like Ronnie (Paul DeAngelo, also of Silent Madness) and Gene (The First Turn-On!!’s Frank Trent Saladino), Angela is almost totally on her own in the hateful junior-high jungle that is Camp Arawak. Then she has the foul luck to cross paths with Artie (Owen Hughes), the head cook— that chickenhawk head cook I mentioned a few sentences ago. Angela has been so depressed since she got to camp that she hasn’t eaten in days, and Ronnie gets sufficiently worried about her to take her back to the kitchen to see if Artie can’t find something more to her liking than whatever hog-slop he’s serving up for lunch that afternoon. As soon as Ronnie leaves to go deal with some sort of emergent situation, however, Artie leads Angela back into the walk-in pantry, and suggests to her that if she doesn’t like the food, maybe she’d enjoy munching on his wang for a while instead. Ricky comes looking for Angela just as Artie is unbuckling his belt, and he and his cousin tear ass out of the kitchen faster than any fourteen-year-olds you’ve ever seen.

Thus I believe we already know who the culprit is when one of the campers sneaks into the kitchen a bit later, and causes Artie to pull a man-sized tank full of boiling water over onto himself. The filmmakers seem to want us to be uncertain for now as to whether Ricky or Angela is the killer, but right from the get-go, there’s no possible way it’s anyone but the girl. In any case, Artie isn’t the last one to taste her vengeance, either. After Mike (Tom Van Dell) and Kenny (John Dunn), two of Billy’s Buttpoles, subject Angela to an especially merciless ragging when she snubs their invitation to go skinny dipping with them, Kenny’s drowned body washes up on the lakefront the next morning, along with the canoe he’d taken another girl for a ride in following the (all-male, as it turned out) skinny dipping party. Mel hushes up the drowning just like he did Artie’s “accident,” and things seem to go smoothly for a while. But then somebody traps Billy in a bathroom stall by barring the door with a broom handle, and drops a gigantic nest of bald-faced hornets in with him. After this third, rather less accidental-looking death, all but some 25 of the campers call their parents to bring them home, and Mel comes to believe that somebody is deliberately out to ruin him. His prime suspect: Ricky, who was involved in conspicuous altercations with both boys shortly before each turned up dead, and who had been seen walking into the kitchen in search of Angela on the day when Artie was scalded.

Meanwhile, Angela, against all odds, has made a friend— possibly even a boyfriend. Ricky’s old buddy, Paul (Christopher Collet, later of The Langoliers), is the only boy at Camp Arawak who has consistently treated Angela with decency and compassion (apart from her cousin, I mean), and he’s been so successful at opening her up that he’s even got her talking a little. This only makes the girls with whom Angela shares her cabin hate her even more, however, and one of them— Judy— begins trying to come between Angela and Paul out of spite. She gets her chance, too, when Paul takes greater liberties than Angela is ready to permit (the boy’s groping oddly triggers an old memory of Angela and her brother spying on their dad and his boyfriend [!] in bed together), and she withdraws her affections from him. Judy moves in, and does it in such a way that Angela can’t fail to notice. And although Angela initially seems to forgive Paul when he comes crawling contritely back to her a day or two later, he ends up the final victim of an all-night bloodbath that also claims Judy, Meg, Mel, and all the remaining members of Billy’s old crew. We’ll also get a parting shot that has relatively little to do with the story proper (beyond adding the most compelling reason yet to the litany explaining why Angela is so fucked up), but which gives Sleepaway Camp something that very few 80’s slasher movies can honestly claim to possess— a scene which nobody, having once seen it, can ever possibly forget.

Far from being just another by-the-numbers slasher movie, Sleepaway Camp is in several respects almost unique within its genre. It doesn’t just eschew the convention of the Final Girl, but goes so far as to abandon the expected Ten Little Indians-derived body count structure altogether. Unusually for a slasher film, Sleepaway Camp includes quite a number of innocent bystanders among the cast, and Angela is careful to spare them throughout; it’s revenge she’s after, not indiscriminate mayhem. This means that we see little of the relentless winnowing of characters which is the typical slasher’s most noticeable trait. Instead, a few solitary murders meant to punish specific incidents are spaced out across the film, which is then climaxed by an outburst of violence directed against everyone who has ever done Angela wrong. (Indeed, one is tempted to imagine her planning on going home to have at Aunt Martha after she’s through with her enemies at Camp Arawak.) The early killings are all set up so that they can plausibly be passed off as accidents, while the rest occur so rapidly that you really can’t fault the other characters for failing to pick up on them until it’s too late. What’s more, because the focus of the film is always on Angela herself, there is simply no room here for the traditional fight to the death between the killer and her last intended victim. In the absence of a non-murdering protagonist whom Angela would have any reason to attack, it falls to the authorities (in the form of Ronnie and his fellow counselors) to uncover her killing spree, and when they do, writer/director Robert Hiltzik makes such a strong presumption of efficacy in their favor that he doesn’t bother with a showdown at all. The counselors catch Angela sitting by the lakeside cradling Paul’s severed head, a combination of flashback and dolly-out reveals her shocking secret (which, for once, truly is shocking), and that’s the end of that. It’s possible to take issue with the elliptical conclusion or the languorously episodic story structure on dramatic grounds, of course, but one thing that cannot be argued in good faith is that they bear any meaningful resemblance at all to the slasher norm, let alone adhere rigidly to the formula.

The same can also be said about the way Sleepaway Camp deals with the parts of the story that don’t directly concern the murders. To begin with, we’re talking about a sizable proportion of the running time here, which is remarkable in itself. Sleepaway Camp spends a great deal of time simply detailing the routine of life at Camp Arawak, and the way it does so mostly rings true. It is admittedly hard to swallow Artie— a pedophile so unapologetic that he muses to his coworkers, “Look at all that young, fresh chicken,” while they watch the campers piling out of the bus— being allowed to hold a job that involves him coming within a quarter of a mile of children, but I found everything else about Camp Arawak bitterly convincing. The lameness of the scheduled activities, the belittling attitude of both staff and campers toward anyone who recognizes and takes exception to that lameness, the eagerness of the kids to be shitty to each other— even to their ostensible friends— for no detectable reason… Like I said, it’s just the way I remember it from Arlington Echo back in 1986. Also true to life is the fact that these really are kids we’re dealing with. The inmates of Camp Arawak range in age from around twelve to probably somewhere in the late teens, and while the older kids are played, as usual, by actors who have a good ten years on their characters, the casting for the younger ones is more or less age-appropriate. Probably as a direct consequence of this, Sleepaway Camp also differs from its competitors in featuring much less sex and much more awkward striving after sex-like surrogate activities, which jibes quite neatly with the stories I was told by my summer camp-going friends in the mid-to-late 1980’s. Paul’s stolen goodnight kiss and the fraught negotiations for feeling-up privileges that go on between him and Angela by the lake that fateful night seem much more authentic than the non-stop fuck-a-thon enjoyed by Kevin Bacon’s character in Friday the 13th. For that matter, compare the Bacchanalian coed skinny dipping party from Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter to Billy and the Buttpoles’ futile efforts to talk even one girl into joining theirs. All in all, it was such a surprise to see a slasher movie whose creators so obviously remembered the realities of early teenage life that I didn’t mind at all how little slashing there was until the final act. And even if you do, it’s worth sticking with this film until the end anyway. If nothing else, Sleepaway Camp is still the reigning North American champion in its league when it comes to psychosexual sickness.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact