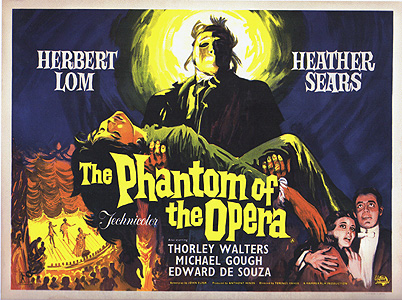

The Phantom of the Opera (1962) **½

The Phantom of the Opera (1962) **½

It’s amazing how few generations it can take for adaptation drift to render a story unrecognizable. Hammer Film Productions’ The Phantom of the Opera was only the third movie to be made from Gaston Leroux’s novel of the same name— or at any rate, it was only the third movie that can be confirmed as such. (There are a few lost films from the 1910’s that sound intriguingly like possible ancestors of Universal’s classic silent interpretation, but the surviving information about them is too sparse to support any firm conclusions one way or the other.) Yet this third version has already strayed just as far from the source material as the famously unfaithful adaptations directed by Dwight Little and Dario Argento in 1989 and 1998, respectively. On one level, that might be taken as simply another example of the old Hammer formula— after all, neither The Curse of Frankenstein nor Horror of Dracula displayed more than the occasional stray codon of their predecessors’ DNA. What’s curious, though, is that there was a very specific reason why those first two Hammer gothics came out looking the way they did, and that reason doesn’t seem to apply here. In both cases, Hammer’s primary objective was to inoculate themselves against copyright lawsuits by differentiating their movies as far as possible from the iconic versions released by the famously litigation-happy Universal in 1931. But by 1962, Hammer had been in partnership with Universal for some years. Indeed, Universal would distribute this Phantom of the Opera in the United States. And beyond that, to the extent that the Hammer Phantom owes anything to earlier iterations of the story, it borrows most recognizably from Universal’s own 1943 remake.

Somebody really has it in for Saint Joan, the new opera by up-and-coming London composer Lord Ambrose D’Arcy (Michael Gough, of Horror Hospital and They Came from Beyond Space). Everywhere producer Harry Hunter (Edward De Souza, from The Kiss of the Vampire and The Golden Compass) goes around the Aberdeen Theater on opening night, he sees evidence of a mysterious grudge at work. The advertising broadsheets outside the building have been mutilated. The orchestra is suffering from an epidemic of slashed drum heads. Rossi the conductor (Martin Miller, from Latin Quarter and Children of the Damned) complains of stolen sheet music. And Maria the lead soprano (The Devil Rides Out’s Liane Aukin) is on the verge of hysterics— something about a one-eyed man in black appearing from nowhere in her dressing room, and then vanishing just as inexplicably. Meanwhile, Lattimer (Thorley Walters, from Twisted Nerve and Vampire Circus), the Aberdeen’s manager, must explain to His Lordship why he’s reporting a sellout crowd even though one of the mezzanine-level boxes— normally reckoned the best seats in the house— is conspicuously empty. Lattimer says he’s actually given up trying to sell the seats in that box. D’Darcy may believe what he likes, but it’s reputedly haunted, and none of the theater’s regular customers will sit there. All the commotion prevents anybody from noticing the gimpy little hunchback (Ian Wilson, of Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire and The Day of the Triffids) skulking around backstage, but I’m thinking he’s really the thing they should all be watching. Odds are he’s the one who waylays one of the stagehands, hangs him from the set rigging, and tosses the body out where the whole audience can see it right in the middle of Maria’s first solo.

Maria wisely decides that she wants nothing more to do with Ambrose D’Arcy or his opera after that. The police may rule the stagehand’s death a suicide, but she isn’t buying that for an instant. Given, however, that The Show Must Go On, Hunter begins auditioning sopranos to take Maria’s place. He quickly finds a very promising young singer named Christine Charles (The Black Torment’s Heather Sears). Christine is inexperienced at the required level of performance, and will clearly need some work before she’s ready to play the title role in Saint Joan, but anybody with ears can tell that she’s well endowed with native talent. Hunter fails to realize, though, that D’Arcy prefers to recruit his divas on a casting-couch basis. Christine’s real audition is yet to come, when His Lordship has her back to his place after taking her out to dinner. Interesting, then, that someone should speak to Christine from an invisible hideout in the makeup studio, warning her what to expect from D’Arcy. You figure this unseen informant is also the mastermind behind all the opening-night sabotage?

Lord Ambrose does indeed perform as advertised that night. Luckily for Christine, Harry coincidentally goes to dine at the same restaurant, and she is able to use him as her escape route from a “private lesson” at D’Arcy’s flat. After all, it would only make sense to have the producer of the opera on hand for such a session, but D’Arcy’s intentions are such that there’s no point in the exercise unless he and Christine can be alone together. Outmaneuvered, Ambrose sullenly withdraws, leaving Christine to join Harry for dinner instead. Inevitably, the pair start the accompanying conversation by talking about the opera, which is the one thing they already know they have in common. Harry mentions the vandalism and weirdness that have plagued Saint Joan since it began preproduction, and that leads Christine to tell him about the voice in the makeup studio. Suspecting at once that there may be a connection, Hunter suggests an investigatory visit to the theater— a visit which yields rather more than either one of them bargained for. Although they are unable to find the hiding place from which Christine was given her anonymous tip about D’Arcy, they both hear the mysterious voice once again, and while Harry is distracted (the hunchback’s somewhat excessive idea of a diversion is to murder the night-shift rat-catcher!), Christine actually meets its owner (Herbert Lom, from Mysterious Island and Asylum) in person. Would you believe he’s a black-clad man wearing a featureless mask that obscures everything of his face save a single, baleful eye? It seems that the masked man means to abduct Christine, but her screams bring Harry running to her before the Phantom of the Opera can carry out the kidnapping.

Harry and Christine will have plenty of time to mull over their eventful night at the theater, because D’Arcy gives them both the sack in revenge for his cock-blocking. As it happens, though, they spend most of the next day chasing down what Hunter initially believes to be a totally unrelated mystery. Christine rents a room in the boarding house run by the widow Tucker (Renee Houston, of Repulsion and Legend of the Werewolf), and while the girl gets herself ready for a commiseratory day out on the town with Harry, he chats with the landlady in the parlor. Most of Mrs. Tucker’s lodgers are musicians, and she passes the time by telling the tragic story of Professor Petrie. Petrie had been a music teacher at the academy (wherever that is), and a composer of considerable ability. His work was never published, however, except presumably a few pieces which Mrs. Tucker herself sold after the professor’s death. That’s a bitter irony, too, because as she recollects, Petrie actually died in the act of negotiating a publishing deal. He was killed in the fire that gutted the offices of G. Piggott, Jobbing Printer, several years ago. Intrigued, Harry convinces Christine to put off lunch in favor of calling at Piggott’s, where an interview with master printer Weaver (Keith Pyott, from Village of the Damned and Bluebeard’s Ten Honeymoons) sheds interesting new light on the subject. Mrs. Tucker’s memories are a little off on the details; there was a fire at the printer’s, and somebody was caught in it, but if the poor bastard died, he certainly didn’t do so on the premises. The victim broke in after hours, presumably to ransack the place for something saleable, and must have dropped some tobacco embers in the voluminous litter of paper scraps that virtually covered the floor of the shop. He apparently tried to put out the fire, but the jar he dumped on it contained not water, but nitric acid for use by the engravers. The policeman who saw him flee described injuries more consistent with a face full of acid backsplash than with exposure to heat and flame. Hearing that sends Harry to the nearest police station, where Sergeant Vickers (John Harvey, of X: The Unknown and The Stranglers of Bombay) adds one final detail: the acid-scarred burglar leapt into the Thames, where the current quickly carried him out of sight. One might ask at this point why Hunter cares what happened to Professor Petrie— Christine certainly does. It all comes down to Saint Joan. Harry couldn’t understand how a philistine like D’Arcy could write an opera at all, let alone one as good as that. Now he has his answer, or so he believes. Lord Ambrose didn’t write Saint Joan, but rather bought it from Mrs. Tucker after its real author, Professor Petrie, was dead.

To those who’ve been paying any attention at all, it should be obvious by now that the operative clause in the sentence before last is “or so he believes.” Petrie, of course, is not dead at all; he’s the masked man prowling around the Aberdeen Theater and making life difficult for everyone attempting to put on his opera. And the reason Petrie has been making such a pest of himself is that D’Arcy wasn’t the person to whom Mrs. Tucker sold some of the professor’s old sheet music. Rather, D’Arcy screwed Petrie on a major publishing deal, giving him only £50 for ten years’ worth of compositions, and then underhandedly passing them off as his own work. The fire at Piggott’s was no random accident, either. Petrie broke in expressly to burn the entire print run of the misattributed Symphony #1 in A Major, and to destroy the printing plates by pouring acid all over them. He just wasn’t expecting the fire to build so quickly, or the acid to be so splattery. None of that, however, is as important now as the fact that Petrie has heard Christine sing. With her in the lead role, he wouldn’t mind so much for Saint Joan to go into performance, but first (as we’ve already established) she’s going to need some extra training. That’s okay, though— there’s nothing wrong with Christine’s singing that a little kidnapping and captivity wouldn’t fix…

In general, I would not consider it a positive sign that a Phantom of the Opera movie proceeds primarily from the innovations of the Claude Rains version; I refer you to my review of the ’43 Phantom for a detailed discussion of why not. Director Terrence Fisher and writer Anthony Hinds have thus done something most unexpected, devising a retelling of the story that redeems much of what didn’t work in its immediate predecessor. By removing all trace of a romantic attachment between the Phantom and Christine, so that he regards her strictly as the one singer worthy to interpret his work; by pushing the events that left Petrie disfigured and insane far enough into the past to make it plausible for legends to spring up around him; by making the unscrupulous music-thief not just a major character, but the movie’s true villain— in these ways, Hinds has restored the power and credibility that the character lost when he was redefined as a kindly old composer driven mad by a dirty business deal and a face-full of engraver’s acid. By showing us enough of Saint Joan for us to follow and grasp its story; by putting some effort into its staging; by setting it to a score that doesn’t suggest a B-grade 30’s musical comedy with delusions of grandeur— in these ways, Fisher has made a virtue of the previously annoying focus upon what happens on the theater stage, conveying a serious sense of what is at stake here from Petrie’s perspective. The simplest and most effective improvement, though, is the bare fact that we aren’t introduced to Petrie as Petrie. The film begins with him already a fearsome and enigmatic figure, and only gradually are we given to understand how he became what he is. Not only does that give the Phantom back some of the menace that he had in both the book and the 1925 film, but it also gives the official protagonists something worthwhile to do in the hour before Christine’s abduction. Whereas before the various Raouls and Anatoles and Christines were pretty well useless on their own, this version makes the central couple both proactive and effective. They solve the mystery of the Aberdeen Theater (well, okay— so mostly Harry solves it), without the help of any skulking Persian detectives-ex-machina. And while we’re on the subject of The Phantom of the Opera’s mystery aspect, I really like the unusual touch of realism whereby none of the people Hunter interviews while trying to figure out what became of Professor Petrie can agree on the details of the story— and whereby none of their versions turn out to be accurate except in the overall contours, anyway.

Nevertheless, I can’t fully get behind this Phantom of the Opera. It’s a little too diffuse, for one thing, not least because Hunter makes the connection between the supposedly deceased Professor Petrie and the masked malefactor at the theater only after Christine is kidnapped. All that detective work over Petrie’s disappearance seems a bit much to do on a lark, and it isn’t as though Harry doesn’t already have ample reason to believe in the Phantom’s reality the first time he hears the professor’s name. The murderous hunchback is insufficiently developed and insufficiently integrated with the other aspects of the story. The burn makeup Herbert Lom wears when he is unmasked (under circumstances that don’t make any sense, I might add) is both unimaginative and risibly bad— as in, very nearly Evil of Frankenstein bad— with the result that Lom’s is the only movie Phantom I’ve seen who is scarier with his mask on. (To be fair, that’s also partly because the mask itself is as brilliantly unsettling as the face beneath it is half-assed and silly.) The most frustrating thing about Hammer’s The Phantom of the Opera, though, is that Lord D’Arcy receives no meaningful comeuppance. I’m not quite sure what would have been an appropriate fate for him under the terms of the story as presented here, but surely his conduct throughout calls for something a little stronger than to see Petrie’s true face, and then to run away screaming like a Mantan Moreland character. This Phantom of the Opera doesn’t deserve the virtual invisibility that has been its lot for most of my lifetime, but I can see why nobody’s been in any great hurry to rehabilitate its reputation.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact