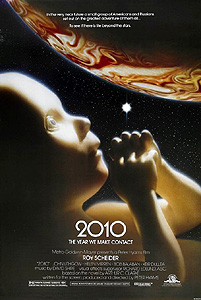

2010/2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984) **

2010/2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984) **

There are two adjectives that are deployed almost every time anyone describes 2010/2010: The Year We Make Contact. The first of these is “long-awaited;” the second is “disappointing.” I was only ten years old in 1984, so I’ll have to take the critics’ word for it that folks were out there eagerly anticipating a sequel to 2001: A Space Odyssey, but if that’s true, then I can certainly understand their disappointment when 2010 finally showed up. As I believe I’ve already made sufficiently clear, I’m not one of the old movie’s fawning fans, but I can still see that this sequel represents a big step down from it in every department except star power.

As ought to be obvious, nine years have passed since the Discovery 1’s mission to Jupiter ended in tragedy. Back on Earth, there are three main questions: What is the gigantic copy of the Tycho Monolith that mission commander David Bowman (Keir Dullea, whom we shall indeed be seeing again this time around) discovered in orbit around Io? What caused the malfunction of the HAL 9000 computer that led it to kill four of the Discovery’s five human crewmembers? And what exactly happened to Bowman when he left the ship in a space pod to examine the giant monolith more closely? Nine years of fruitless efforts to get inside the Tycho Monolith have brought the scientists of the American space agency no closer to answering the first question. Similar feverish work by HAL’s creator, Dr. Chandra (Close Encounters of the Third Kind’s Bob Balaban), have been equally unproductive with regard to the second. As for the third, the only clue anyone on Earth has to that mystery is Bowman’s final radio transmission, sent as he first approached the monolith: “My God— it’s full of stars!” No one has any idea what in the hell that was supposed to mean. Obviously the only way to learn what really went on back then in Jupiter’s neighborhood is to send another manned mission out to the Discovery, which is still in orbit around Io. Such an undertaking is on the back burner right now, however, because the US and the USSR are on the brink of war over some unexplained bad business in Honduras. The American government has reasonably concluded that we should wait to send men off to another planet until we’ve figured out for certain whether or not we’re going to incinerate this one.

That’s where the situation stands on the day when Russian scientist Dimitri Moisevich (The Boston Strangler’s Dana Eclar) drops in on Dr. Heywood Floyd (now played by Roy Schieder, of Jaws and The Curse of the Living Corpse, who— let’s face it— has much more marquee value than William Sylvester) at his place of work. Moisevich has a proposition for Floyd. While work on the Discovery 2 grinds slowly ahead, its Soviet counterpart, the Alexei Leonov, is nearing completion; the Russians should beat their rivals to Io by a matter of years. The trouble is, the cosmonauts aboard the Leonov will have no way of learning anything meaningful from doing so— they certainly won’t have the technical know-how to hack into HAL’s memory banks, nor could they interpret the data within them even if they did. Despite (indeed, perhaps because of) the strained relations between the two superpowers, Moisevich suggests that he and Floyd should collaborate. Floyd (who, as the organizer of the original Discovery mission, has something of a personal stake in the answers to those questions I laid out earlier) will assemble a small team of American scientists, who will then join the cosmonauts on the Leonov when they blast off in about four months. And as a final goad to action, Moisevich mentions something that he correctly believes Floyd and his colleagues haven’t noticed— the Discovery’s orbit is decaying, and the dead ship will crash on Io long before the Discovery 2 is ready to fly.

It’s a tough sell, but Floyd and his successor as the head of the space agency are eventually able to convince the president (who, incidentally, turns out to be Arthur C. Clarke when we see his face on an issue of Time Magazine; the Soviet Premier with whom he shares the cover is Stanley Kubrick!) to allow the mission, and to put Floyd himself in charge of its American aspect. As his two companions, Floyd selects an old engineer buddy of his, Dr. Walter Curnow (John Lithgow, from Twilight Zone: The Movie and The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai: Across the 8th Dimension), along with Dr. Chandra, who has been itching to have a look at HAL for almost a decade. Neither Floyd nor Curnow is entirely certain that Chandra can be trusted (they worry that his notorious affection for the sentient machines he builds will blind him to the danger inherent in bringing HAL back online), but that distrust is nothing compared to the one with which all three Americans are greeted by mission commander Tanya Kirbuk (Helen Mirren, from Caligula and Excalibur). Sounds like a fun trip, huh?

Like last time, most of the crew will spend the greater part of that trip in hibernation. Floyd and the senior cosmonauts get woken up early, however, when the Leonov’s sensors detect something highly unusual on the surface of Jupiter’s ice-encrusted moon, Europa. The data aren’t entirely conclusive, but it sure does look like there’s oxygen and chlorophyll at the bottom of one of the moon’s deeper craters. The Leonov deploys an unmanned probe to have a closer look, but just as it gets within range of the crater, the probe is destroyed by some sort of energetic discharge, which also has the effect of wiping out all of the data it had thus far transmitted from the Leonov computer’s memory banks. Everyone aboard the ship would kind of like to stick around and study the mysterious phenomenon at greater length, but the Leonov doesn’t have enough fuel for the detour. And maybe that’s just as well, when you get right down to it. Though the Russians are all skeptical, Floyd thinks maybe the probe was destroyed deliberately by whatever alien intelligence is associated with the monoliths, as a warning to stay the hell away from the crater.

Once the Leonov reaches the Discovery, it becomes increasingly clear that Floyd is right. For one thing, cosmonaut Maxim Brajlovsky (Elya Baskin, of DeepStar Six) is killed by exactly the same kind of discharge when Captain Kirbuk sends him out in a space pod to investigate the monolith, establishing incontrovertibly that a connection exists between the monolith’s builders and whatever is going on in that crater. Then Dr. Chandra reconnects HAL, and the really strange manifestations begin. The computer starts receiving enigmatic transmissions warning that the two spaceships must leave the environs of Jupiter within two days, regardless of the fact that neither ship has the fuel to reach Earth except during a narrow launch window more than a month off. What makes these transmissions strange is that HAL can’t trace their source, and that their originator identifies himself as David Bowman. Dr. Floyd understandably doesn’t believe that, at least not until Bowman appears to him in person and repeats the warning. He won’t say why the Discovery and the Leonov need to leave so soon; all he’ll tell Floyd (or HAL either, for that matter) is that “something wonderful” is going to happen.

Both crews could use “something wonderful” right about now, come to think of it. While they’ve been out in space, the situation back home has been getting steadily worse. Diplomatic relations between the rival superpowers have been broken off, the two nations’ governments have expelled each other’s nationals from their respective territories, and sabres are being rattled by both sides all over the place. The most immediate practical outcome of all this foolishness as far as the space travelers are concerned is that the reciprocal expulsion orders have the effect of confining the three Americans to the Discovery and the Russians to the Leonov. This, of course, means that Floyd’s plan for getting both crews home in time to avoid whatever danger is posed to them by Bowman’s Wonderful Something— using the Discovery as a booster to launch the Leonov onto a faster Earthbound trajectory— is now technically illegal. All things considered, the spacefarers should really set aside their governments’ differences and get cracking on Floyd’s proposal. The monolith has just teleported itself into Jupiter’s upper atmosphere, where it is now reproducing itself by the millions, setting in motion a mysterious process that will soon turn the giant, gaseous planet into an auxiliary sun, and the astronauts sure as hell don’t want to be in the neighborhood when that happens!

If 2001: A Space Odyssey may be thought of as a philosophically overreaching, mega-budget reworking of Destination Moon (and that is more or less how I, for one, think of it), then 2010 is an egregiously philosophically overreaching, mega-budget take on Red Planet Mars. 2001 was content to drop hints and raise questions; 2010 sets itself to the task of providing concrete answers. The trouble is that those answers are terribly pedestrian in comparison to what the previous movie implied, painting a totally different picture of the aliens behind the monolith. Both films could fairly be described as theological in character, coming very close to saying outright that the alien intelligence is no less than God itself— but what different Gods they postulate. 2001 comes close to a Buddhist perspective, its extraterrestrial godhead being essentially unknowable even when one lives for a hundred years in its presence, apart from the indisputable point that its program for humanity is one of transcendence. 2010’s God-alien could hardly be more Judeo-Christian if it had sent Bowman aboard the Discovery to re-preach the Sermon on the Mount. In addition to dealing in miracles, the monolith alien now communicates much more directly and explicitly with the human beings it contacts, and of the greatest importance, its aim is not to bring humanity to a higher evolutionary plane, but to usher in a new Utopian era of Peace on Earth and Goodwill to Men— and to men who are entirely human in the present sense of the term, at that. Personally, I prefer the way Red Planet Mars handled the theme; that movie’s creators at least had the courage to come right out and say that Chris and Linda Cronyn had found a vaguely but recognizably Christian God on the planet Mars. Doing it that way at least presents an entirely plausible reason for the end of the Cold War, after all.

Red Planet Mars was also much more consistent in its characterization of the divine extraterrestrial. While the miracle of a Second Creation on Europa certainly jibes with Levantine notions of divine behavior, there is one level on which it is simply not possible to reconcile such an action with the interest the monolith intelligence now displays in guiding— even dictating— human behavior. Do you have any idea what it would do to the Earth’s environment if the solar system suddenly grew a second sun?!?! It’s one thing if the plan is for everybody on Earth to transmogrify into incorporeal fetus-things capable of surviving in open space, as the ending to 2001: A Space Odyssey suggested. But if we’re all supposed to be living on Earth in righteous peace and harmony, then the addition of another star to the vicinity becomes more than a little inconvenient!

I don’t suppose I should be too surprised about that kind of thing, though. If there’s one thing that writer/director Peter Hyams makes clear from the moment the setting shifts from the surface of the Earth to the interior of the Alexei Leonov, it’s that he does not share Stanley Kubrick’s concern for scientific veracity. Gravity aboard the spaceships comes and goes in obedience to no discernable rule or order. Space, for the most part, is as noisy a place in 2010 as it is in any Buck Rogers serial. A diverse and notably Earth-like ecosystem rises up on Europa in what seems to be a matter of weeks. The explanation that eventually surfaces for HAL’s deadly malfunction from the preceding film is as illogical as it is cliched. All in all, it’s pretty pathetic, and really leads one to appreciate the craftsmanship of Stanley Kubrick even at his most careless. I’m just glad I wasn’t one of the people waiting with bated breath for the sixteen years it took for 2001: A Space Odyssey to sprout a sequel...

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact