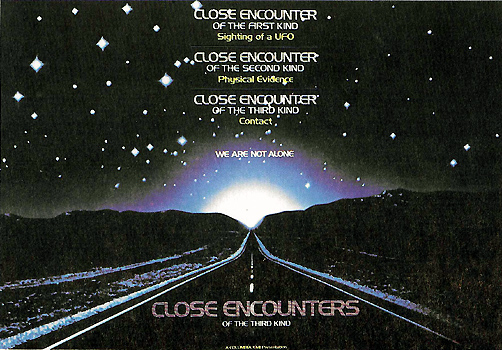

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) **Ĺ

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) **Ĺ

Thereís a very good chance that Steven Spielbergís Close Encounters of the Third Kind is the most overrated science fiction movie of my lifetime. Not that itís a bad film, precisely, but it very definitely does foreshadow (albeit in somewhat less annoying form) all of the most contemptible tendencies which its writer/director would come to display later in his career. Style doesnít just triumph over substance in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, it routs it, resulting in a beautiful, visually arresting movie that is intellectually shallow, seriously under-plotted, and emotionally dishonest to an extraordinary degree.

Extremely weird shit is happening all over the world. In the Sonora Desert, in Mexico, a team of US government-connected researchers led by Frenchman Claude Lacombe (Fahrenheit 451 director FranÁois Truffaut, demonstrating that heís much more appealing in front of the camera than behind it) are called in to have a look at a squadron of TBF Avenger torpedo bombers that have unaccountably turned up on an abandoned-looking ranch. The planes are over 30 years old, but they look like they were manufactured yesterday, and their engines start up without a hitch. Whatís more, the markings painted on the planes identify them as the aircraft that famously vanished in 1945 while on a training mission in the Bermuda Triangle. Something even more inappropriate turns up in Mongoliaís Gobi Desert not much lateró a similarly well-preserved freighter which disappeared from the sea under comparable circumstances. In India, seemingly the entire population of a remote town gathers at the place where they say an object in the sky sang to them, and repeat the mysterious visitorís tune. And much closer to home, the American Midwest is swept with a rash of UFO sightings.

The first contact over American territory occurs when the air traffic control center in Indianapolis detects an unregistered aircraft on a course that could bring it perilously close to a pair of airliners. Though all concerned initially assume the unknown flyer to be a private pilot out on a joyride, the picture changes when the captains of both jets get a look at the mysterious vehicle. Neither man has any idea what heís seeing, but it sure as hell isnít any Cessna or Piper Cub. When air traffic control asks if they want to report a UFO, however, both pilots decline. That airborne encounter is just the beginning, though. In Muncie, Indiana, something lets itself into the home of Gillian Guiler (Spontaneous Combustionís Melinda Dillon) and leads her toddler son on a chase through the woods after trashing the place. Meanwhile, power company lineman Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss, of Jaws) has a run-in with three curious airborne vehicles and a floating ball of insubstantial light when he drives out to help address a sudden and unexplained power failure that has gripped the city and its environs. Neary takes off after the fast and low-flying machines, and in doing so, he nearly runs over little Barry Guiler, who has by that point wandered into the middle of the road and hooked up with a family of stargazing rednecks. Gillian comes along just in time to rescue her son from being flattened, and Neary has only a moment to say hello and apologize before a trio of squad cars comes shrieking over the nearest rise, reminding Roy that he was in the middle of something. Neary gets back into his truck, and joins the cops in chasing the UFOs, but the latter lose their pursers by going aloft just over the Ohio state line. Later that nightó like, 4:00 am lateró when Roy rounds up his wife, Ronnie (Teri Garr), and their four kids to show them the spot where the UFOs ditched him, the Neary family as a whole is less than impressed.

Similarly unimpressed are Royís employers when, over the course of the next week or so, he begins increasingly shirking his duties to dig around for any remaining traces of the UFOs. In fact, the power company guys are so unimpressed that they fire Neary. His escalating obsession with flying saucers has an equally deleterious effect on his home life, as his kids gradually come to see him as a great big weirdo and Ronnie (who seems always to have considered her husband just a touch impractical and irresponsible) loses completely what little patience with Roy she ever had. Especially galling to the family appears to be Royís inexplicable fixation upon some kind of mountain, which he zones out thinking about every time heís confronted with anything conical, cylindrical, or mound-like in form. The final straw comes when Roy has an epiphany of sorts, and begins constructing a large-scale model of his mountain in the living room of the house, using such materials as a 50-gallon trash can, all of the landscaping in the front yard, and the chicken wire with which the next-door neighbors corral their ducks. Ronnie packs up the kids and takes them to her sisterís house, giving every indication that she isnít coming back unless and until Roy seeks psychiatric assistance. Of course, even that might be better than what happens over at the Guiler house. Gillian shares Royís curious monomania, but being a painter rather than a model train set enthusiast, she sketches the mountain obsessively rather than attempting to build replicas of it. The relatively slight disruptiveness of her obsessional symptoms as compared to Nearyís is more than counterbalanced, though, when the aliens return to her house and abduct Barry.

Meanwhile, Lacombe and his fellows are getting closer to solving the mystery of the UFOs. Operating on the theory that the series of tones sung by the peasants in India is intended as some manner of greeting, the scientists have begun transmitting it out into space by means of a radio telescope. Lacombeís team gets a response, but itís not the one they anticipated. Rather than another musical phrase, Lacombeís extraterrestrial correspondents reply with a repeating numerical sequence. No one knows what to make of it until Lacombeís interpreter, David Laughlin (Bob Balaban, from Altered States and 2010), has a look. As Laughlin puts it, before he got paid to speak French, he used to be a cartographer, and he recognizes the series as a set of map coordinatesó specifically, the latitude and longitude of Devilís Tower, a volcanic chimney out in the Wyoming desert. Guess we know what that mountain is now, donít we?

The two halves of the story start coming together when Lacombeís Pentagon partners decide to put the lockdown on the countryside around Devilís Tower so as to turn it into an easily controllable venue for the interplanetary summit meeting which Lacombe believes is approaching. The cover story the generals choose concerns a military nerve gas leakó certainly it sounds scary enough to empty every single person out of a 300-mile radius around Devilís Tower. What the brass havenít figured on is the news coverage of the evacuation being seen by people like Roy Neary. Roy, Gillian, and about ten other people who had some manner of contact with the aliens see Devilís Tower on the television, realize that itís the mysterious mountain thatís been haunting them ever since the night they saw the UFOs, and embark immediately on a pilgrimage to the site, army roadblocks be damned. The officers in charge of building Lacombeís conference center at the foot of the mountain do their damnedest to keep Neary and the other interlopers out, but they canít stop Roy and Gillian from being there at Devilís Tower when the alien mothership lands like a veritable Santaís sleigh of anticlimaxes.

To a certain extent, I recognize that an anticlimax was basically inevitable in a movie that attempts to deal with the subject of first contact with extraterrestrial intelligence on terms that jibed with UFO mythology as it had developed by the late 1970ís. ďRealĒ aliens as they were conceived at the time were just too hell-bent on staying mysterious for the pilots of Close Encounters of the Third Kindís UFOs to do anything but drop in briefly during the final reel, put on a big display of cryptic weirdness, and go home without a word of explanation. But nevertheless, I really did expectó and really do requireó a bit more in the way of an ending than the mothership setting down beside Devilís Tower and inviting Lacombe to join it in a nice game of Simon. As it stands, the original conclusion to Close Encounters of the Third Kind depends completely for its impact upon the brute visual impressiveness of the alien vessel, and after most of 30 years, that really isnít good enough anymore. (Although, to be fair, I remember being blown away by the big reveal when I first saw Close Encounters of the Third Kind at the drive-in as a small child.) Spielberg himself presumably came to recognize the magnitude of that deficiency, for he later re-released Close Encounters of the Third Kind with an extended ending in which the camera accompanies Neary and the soldiers aboard the alien ship before it lifts off. Itís been a good many years since I saw that version of the film, but I donít remember it being all that much more satisfying. After all, the terms of this story are such that no real resolution is possible, because there isnít actually anything to resolve. Earlier in the film, however, when mystery is the name of the game, most of the alien encounter scenes are highly effective. Even when you know what has to be coming, itís a great moment when what Roy Neary takes to be a car coming up behind him on the road rises up into the air and flies over his truck. And nothing in Communion (which plays approximately the same premise expressly for horrific effect) can compare to the abduction of Barry Guiler.

The most damaging defect in Close Encounters of the Third Kind has nothing to do with the aliens, though, or at least not directly. The real trouble is that weíre supposed to like Roy Neary, to be on his side, but the fact of the matter is that his wife is absolutely right about him. Heís nothing but an overgrown kid, and he hasnít a responsible bone in his body. Spielberg tries to distract us from that point by making his kids a pack of insufferable brats and Ronnie a condescending and vindictive shrew, but that doesnít change anything. We can forgive Roy for going a little nuts and building a mountain in his living roomó after all, heís acting under compulsions planted in his mind by forces beyond his control or even understanding. And we can accept that fatherhood is something he just isnít very good at, as we are repeatedly and explicitly shown examples of his parental incompetence during the first third of the film. But getting himself fired for hanging around at the scene of his encounter with the UFOs when heís supposed to be working is another matter, and Nearyís final-scene decision to abandon his family and go gallivanting around the universe with a bunch of aliens is inexcusably selfish and immature. More importantly, Spielberg gives no indication of recognizing that fact; so far as he seems to be concerned, Royís just following his bliss or doing his own thing or whatever other cockamamie hippy bullshit slogan you want to plug in there. Radical expeditions of self-discovery are fine if youíre young and single, but Roy has a wife and four kids who up until recently had been depending on him. Leaving the planet for a cruise on a UFO therefore makes him an asshole, and because Spielberg apparently doesnít see that, itís hard to watch Close Encounters of the Third Kind without coming to suspect that he must be an asshole too.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact