Murder at the Baskervilles/Silver Blaze (1937/1941) **½

Murder at the Baskervilles/Silver Blaze (1937/1941) **½

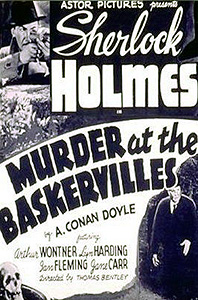

No, this isn’t the sequel to the 20th Century Fox Hound of the Baskervilles; that was called The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. In fact, not only is Murder at the Baskervilles not a Fox production, it wasn’t even made in the United States, and it premiered back home in Britain two years before Basil Rathbone’s screen debut in the role that would virtually define his career. But when Astor Pictures (a very minor company that would win very minor renown in the 50’s by releasing a string of sci-fi and monster movies even chintzier than AIP’s) got their hands on the film known on the other side of the Atlantic as Silver Blaze, they quickly noticed that Sir Henry Baskerville and his daughter were among the supporting characters, and saw in that fact an opportunity to wring a few extra bucks out of what American audiences would otherwise have seen as a very undistinguished B-movie indeed.

Acclaimed private detective Sherlock Holmes (The Terror’s Arthur Wontner, who had portrayed Holmes for the screen on five previous occasions) has evidently been pushing himself rather hard of late, and his old friend, Dr. Watson (Ian Fleming, who had also been Wontner’s Watson in Sherlock Holmes’ Fatal Hour and Sherlock Holmes and the Missing Rembrandt), contends that it is well past time he took a vacation. Fortuitously, Holmes receives a letter from Sir Henry Baskerville (Lawrence Grossmith, from the 1944 version of Gaslight)— with whom he has evidently kept up an acquaintance ever since that hound business twenty years ago— inviting him and Watson out to his estate in Exeter. Sir Henry has a grown daughter now, and both Diana (Judy Gunn) and her fiance, Jack Trevor (Arthur Macrae), are eager to meet at last the legendary genius who dispelled the old family curse once and for all. Despite his general distaste for both idleness and the countryside, such a visit appeals to Holmes (and one suspects that the prospect of finally putting a stop to Watson’s nagging appeals to him even more), and he begins making arrangements for a getaway to Baskerville Hall. Interestingly, it turns out that another of Holmes’s associates is going that way, too, for Inspector Lestrade of Scotland Yard (John Trumbull, of The Murder Party and The Black Abbot) has received a temporary transfer in order to oversee security and crowd control for the upcoming Barchester Cup horse race.

You know who else will be spending the next week or two in Exeter? Professor Robert Moriarty (Lyn Harding, of The Man Who Changed His Mind, reprising his role from The Triumph of Sherlock Holmes), that’s who! One of the big bookies for the Barchester Cup, a man by the name of Miles Stanford (Gilbert Davis, from Condemned to Death and The Sign of Four), is covering about £150,000 worth of bets against a horse called Silver Blaze, placed at a time when Silver Blaze was assessed with odds of 106:1. The trouble is, that horse has unexpectedly blown away all of the competition in the trials, and is now favored to win. If that happens, Stanford is totally fucked. Thus it is that the bookie has come to see Moriarty at his secret lair in a disused London tube station; he’s hoping the arch-criminal will be able to see to it that that troublesome animal does not win the Barchester Cup, and eliminate thereby the threat to Stanford’s business. It’s a little outside Moriarty’s usual line of work, but if Stanford is willing to fork over the necessary £10,000 retainer, he’ll accept the assignment. The professor rounds up his henchmen— Moran (Non-Stop New York’s Gilbert Davis), Barton (Danny Green, from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and William Castle’s The Old Dark House), and Prince (Ralph Truman, of The Crimson Circle and The Bells)— and sets off for Exeter.

Now a horse is a horse (of course, of course), and no one can bribe a horse to throw a race (of course), and that pertains even if the horse is the famous Silver Blaze. The only thing for it is to make sure that Silver Blaze never enters the running at all, and that’s going to entail even more risk than one might expect, because the horse’s owner, Colonel Ross (Robert Horton), is also the local chief of police. Nevertheless, on the morning of the last trial race, Mrs. Straker (The Lodger’s Eve Gray), the wife of the colonel’s stable manager, awakes to find the night watchman dead and both her husband (Martin Walden) and Silver Blaze missing. Ross calls in Lestrade, and Lestrade calls in Holmes. Heaven knows there’s enough suspicion to go around at first glance. The watchman was evidently poisoned with powdered opium in his food, and it just so happens that Mrs. Straker made curry for dinner that night, one of the few dishes with a strong enough flavor to disguise that of the poison. The Strakers’ dog raised no alarm during the night, suggesting that the horse thief was somebody known to it. Jack Trevor paid a visit to Straker a few hours earlier, hoping to raise some emergency cash by selling Colonel Ross one of his polo ponies, and it turns out that he has £5000 riding on the horse who up until recently had been the favorite to win. Also, Silas Brown (D. J. Williams, of The Ghost Train and Maria Marten, or Murder in the Old Red Barn), who owns that formerly favored horse, is an extremely shady character. Obviously we know that Moriarty is behind the whole caper, but he sure as hell had his pick of potential local accomplices.

Back at the beginning of this review, I said that Murder at the Baskervilles would have seemed like an extremely undistinguished B-movie to American audiences, were it not for Astor’s efforts to play up the Baskerville connection. In fact, however, this is a pretty damned important B-movie, for it was the last appearance of Arthur Wontner in the part of Sherlock Holmes. Wontner had no transatlantic reputation to speak of in 1937 (or in 1941, either), but in the years to come, asking a dedicated Holmes fan whether they were a Wontner person or a Rathbone person became almost like asking a Trekkie whether they preferred Kirk or Picard. Mind you, Jeremy Brett seems to have shut down that longstanding argument for good, but for decades, Wontner had a large and vociferous cheering section proclaiming him the cinema’s definitive Sherlock Holmes. If Murder at the Baskervilles is anything to go on, I can kind of see why, too. To start with, he looks exactly like Holmes as drawn by the illustrators for the magazines that originally published most of Arthur Conan Doyle’s fiction. He also has a self-possessed dignity about him that contrasts sharply with Basil Rathbone’s more flamboyant approach to the character, and like Reginald Owen in A Study in Scarlet, he can deliver the usual Holmes put-downs without coming across as an insufferable prick. On the other hand, Wontner is nothing if not stuffy, and while stuffy might work for the rather aged Holmes of Murder at the Baskervilles (set twenty years after the hound case, remember), it doesn’t leave much room for the eccentricities that distinguish the character from any other Steam Age hero detective.

What even Wontner’s most ardent partisans were usually willing to concede was that the star of the show was often let down by his material, and some of that can be observed in Murder at the Baskervilles, as well. There’s simply no getting around what a cheap and shoddy movie this is, with sadly obvious rear-projection backgrounds in the “exterior” shots, a few tawdry fanfares standing in for a musical score, and one automobile to be shared among all the characters who are ever seen driving. But more importantly, there’s the issue of Professor Moriarty. B-Movie Message Board regular Paul “Supersonic Man” Kienitz posited not long ago that the mere fact of a Holmes movie featuring Moriarty as the villain is a strong suggestion that the filmmakers have missed the point of Doyle’s stories about the detective, and have failed to understand what it is about them that their fans like. I think he’s right, too. After all, it rather removes the mystery from the mystery to know that whatever the crime may be, there’s that same proto-supervillain behind it. In Murder at the Baskervilles specifically, the problem is compounded by the obvious mismatch between an evildoer of Moriarty’s supposed standing and the triviality of the scheme in which he is engaged. Horse-napping hardly seems a worthy occupation for somebody whose nickname is the Napoleon of Crime! And indeed, Moriarty does not figure in Doyle’s version of “Silver Blaze” at all; he appears here solely in order to beef up the running time and to add a bit of action, both functions which Miles Stanford could easily have been made to perform himself. Furthermore, layering the villains this way has the unfortunate effect of sidelining the mystery plotline, which is what we’re really here to see, and which is handled with considerable finesse and effectiveness in and of itself. It’s just that it must end well before the movie does, in order to set up a predictable and mostly uninteresting confrontation between the two arch-nemeses. The one good thing Moriarty brings to the movie (although, again, Stanford could probably have been written so as to do this job just as well) is an opportunity for Ian Fleming’s Watson to seize the spotlight for a few minutes. Watson has not fared well in the movies, for the most part. He gets turned into comic relief, reduced to an ineffectual cheerleader telling us all how very fucking smart Mr. Holmes is, and in worst-case scenarios, made over into such an all-around butt-monkey that you wind up wondering how he ever managed to earn that M.D. of his in the first place. For the first hour or so, Murder at the Baskervilles gives Watson so little to do that you simply assume that it will be more of the same, but once Moriarty’s thugs capture him, it’s a whole different story. As Watson stares death in the face, Fleming suddenly starts acting like this is his movie instead of Wontner’s, and an entirely new picture of the relationship between Watson and Holmes emerges: Holmes might be the brains of this operation, but Watson is the balls. For anyone who’s ever gotten sick of seeing Watson get crapped on by one screenwriter after another, that scene will make Murder at the Baskervilles worth a look all by itself.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact