The Mistress of Atlantis/The Lost Atlantis (1932) **½

The Mistress of Atlantis/The Lost Atlantis (1932) **½

The international marketing of movies was both cheap and simple during the silent era. All it required was to snip out the intertitles and to replace them with new ones translated into the local vernacular. As with every other aspect of the film business, however, the coming of sound introduced big and expensive hassles. Subtitling, the simplest approach to the problem, would have negated to some extent the central appeal of the talkies— that the audience got to listen to the film instead of reading it— and doesn’t seem to have come into use until after the novelty wore off of the talking picture. Overdubbing meant hiring new writers to devise translated scripts that would both preserve the sense of the original dialogue and at least broadly match the actors’ mouth movements. It also meant hiring new casts to deliver that dialogue, new sound recordists to capture it, and new editors to synch it up with the existing film. In the late 1920’s and early 1930’s (and in comparison to the simple cut-and-splice that had sufficed only a few years before), all that effort and expense must have seemed tantamount to recreating the movie from the ground up. What’s more, in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States— countries with technologically advanced film industries, in which synch-sound very rapidly became the norm— dubbing was perceived as chintzy and low-class. Thus it was that for the first several years of the sound era (that is, until rising production costs made it no longer economical to do so), the major studios in all the synch-sound countries sometimes shot multiple versions of movies they expected to have wide international appeal. In America, this mostly meant Spanish-language parallel productions for export to places like Mexico and Cuba, although some movies (like MGM’s The Unholy Night) had French-speaking doppelgangers instead. In Europe, however, things could get very complicated indeed. On the other side of the Atlantic, smaller domestic audiences meant greater reliance upon export profits, but exploiting nearby foreign markets meant contending with a multitude of different languages. Italy and Spain generally post-looped the sound even in movies meant for domestic consumption, so they weren’t as much of a problem. But industry standards in Britain, France, and Germany seemed to require custom-made export versions, and the early 30’s often saw films being shot in triplicate in order to satisfy the demands of all three markets.

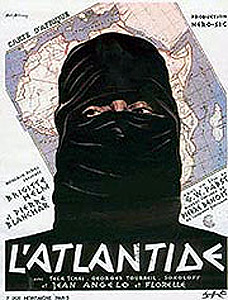

Georg W. Pabst’s The Mistress of Atlantis was part of one such threefold production, and it illustrates just what a headache the practice could be. Pabst filmed it simultaneously with the French-language L’Atlantide and the German-language Die Herrin von Atlantis, but a combination of linguistic obstacles and box-office calculations forced him to use three different core casts. Brigitte Helm, who spoke both English and French with fair facility in addition to her native German, was able to assay the title role in all three versions (trading on the femme fatale image she had established in Metropolis and two successive versions of Alraune), but she would do so opposite a bewilderingly recombinant cast of male leads. Vladimir Sokoloff (who later worked as a character actor in Hollywood— look for him in Monster from Green Hell and I Was a Teenage Werewolf) appeared in the German and French versions, but not the English. Jean Angelo (reprising his performance from 1921’s silent Queen of Atlantis) seems to have played in the French and English versions, but not the German. Five other key performers can be seen in only one version each, while the same extras and bit-players show up across the board. It must have been incredibly trying to keep track of it all, and no doubt there’s a very good reason for it if Helm often seems both bored and exasperated in the English-speaking version (the material for which was reportedly always shot last).

The Mistress of Atlantis takes as its starting point the intriguing premise that the fabled lost civilization was swallowed up not by the sea, but by the Sahara desert. Two French Foreign Legionnaires are listening to a radio broadcast of an archeologist making precisely that contention in an address to a gathering of his fellows when one of the soldiers, Captain St. Avit (John Stuart, later of Paranoiac and Enemy from Space), tells the other that the scientist is exactly right. St. Avit knows this because he once saw Atlantis with his own eyes. In fact, he sojourned there for a matter of months two years ago.

In the ensuing flashback, Captain St. Avit is merely Lieutenant St. Avit; the captain is named Morhange (Angelo), and he is not just St. Avit’s commander, but also his closest friend. The two officers have been assigned to foray south into the Sahara in the hope of feeling out the political sympathies of the Tuareg desert nomads, who could prove most valuable to the French colonial government if they could be bought out or otherwise co-opted. For safety’s sake (and secrecy’s as well), they’ll make most of the trip in company with a salt caravan bound for Timbuktu— I can’t really explain what purpose is supposed to be served by bringing along a female Western journalist (Gertrude Pabst, the director’s wife), and since she disappears from the story almost immediately after being introduced, I don’t think the various screenwriters can, either. In any event, the Frenchmen separate from both the reporter and the caravan near the foot of an uncharted mountain range, bringing along only a few camels and a single native guide. They find a Tuareg quickly enough, but he’s in very bad shape, and the guide swears that there are no villages anywhere nearby; one can only assume that Sigha ben Sheik had been on a mission of his own. The Frenchmen almost immediately find themselves dependent upon the Tuareg, for their guide is soon killed from ambush by tribesmen whom Sigha ben Sheik identifies as the enemies of his people. That leaves him the only one who knows the way through the mountains. All is not as it seems, though. Those “enemies” are in fact a branch of the Tuareg tribe themselves, and Sigha ben Sheik is leading Morhange and St. Avit into a trap.

The warriors who overrun the legionnaires’ campsite a few nights later don’t kill their prey, however, but merely carry them off to their home in captivity. That home is nothing less than the legendary Atlantis, hidden away from the eyes of the world within the impregnable mountains. St. Avit has all this explained to him by Count Velovsky (Gibb McLaughlin, from Juggernaut and The Spell of Amy Nugent), an eccentric Frankified Russian who is one of only two other Westerners within the city walls. The other is a drunken, drug-addled Swede named Ivar Torstensen (Mathias Wieman). Neither of these men will take St. Avit to wherever Morhange is being held, nor even tell the lieutenant where that might be. All St. Avit can get out of them is a bunch of cryptic mutterings about someone called Antinea— the goddess who rules over the ancient city, if Velovsky is to be believed. St. Avit will find out all about Antinea soon enough, for she has taken an interest in him and his captain. This actually almost gets St. Avit killed, for the “goddess’s” summons provokes an outburst of jealous fury from Torstensen. When the soldier eventually overcomes him, the despairing Torstensen kills himself with a broken brandy decanter.

Antinea certainly comes across as at least semi-divine in the lieutenant’s first brush with her: reclining on a divan in the most luxuriously appointed chamber he’s yet seen in the desert city, surrounded by slaves and tamed cheetahs, beautiful, imperious, and possessed of all the glacial impassivity of untrammeled royalty. St. Avit demands to know what has become of Morhange. She ignores the question. Antinea invites St. Avit to play chess against her, with his freedom as the stake in the game. When he takes her up on the challenge, she trounces him effortlessly and banishes him back to his room in Velovsky’s quarters. The net result of this performance is that St. Avit becomes every bit as obsessed with Antinea as Torstensen had apparently been. She, meanwhile, greatly prefers Morhange, who is impervious to her charms and thinks only of escape. Thus is the main conflict of the story set in motion, as St. Avit’s bizarre infatuation with the Mistress of Atlantis gives her a potentially deadly weapon to use against the stonewalling Morhange. And while that asymmetrical rivalry is playing out, Count Velovsky at last opens up and reveals that Antinea’s origins are substantially less than numinous— not that it changes St. Avit’s opinion of her any, you understand, or makes him any less willing to consider murdering his best friend on her say-so.

Georg Pabst is an extraordinarily well-respected director, sometimes described as the greatest working in Germany during the late Weimar period. Consequently, I find it most ironic that The Mistress of Atlantis should so closely resemble an early Jesus Franco movie. I mean, nobody ever so much as called Franco the greatest director working down the street from his house the Tuesday before last! The parallels are incontestable, though. There’s a deadly seductress, an old weirdo who knows more than he cares to tell, a man hopelessly in thrall to a love that is sure to destroy him eventually. The setting is studiedly exotic, the pacing languorous, the narrative so loose-jointed that it falls apart completely the second you ask any serious questions of it. Hell, there’s even a ribald nightclub scene that comes out of nowhere, stops the movie in its tracks, and leaves the audience gaping in sheer astonishment. You really could release this movie with phony packaging, credits, and main titles, claiming an early-60’s release date and billing it as “Jesus Franco’s She,” and hardly anybody would notice the subterfuge. Those who have been reading my reviews for a while will doubtless have surmised by now that I was rather taken with it in spite of its flaws. The Mistress of Atlantis has a weird, dreamy quality that turns its muddled and inconclusive script into an asset. You spend the whole movie having no more idea what’s going on than Lieutenant St. Avit, but that seems to have been Pabst’s intention— and while we’re on the subject, John Stuart capably conveys the soldier’s helplessness and confusion, too. Brigitte Helm is somewhat underutilized (and somewhat overdressed, to my taste…), but does project at least a hint of the necessary seductive force. It’s a mystery to me, however, what she could possibly see in Jean Angelo’s Morhange. But probably the greatest strength of The Mistress of Atlantis is Atlantis itself, together with the frightfully inhospitable North African locations. Whereas most lost-race movies tend to go overboard in presenting their forgotten civilizations as gaudy utopias (or gaudy anti-utopias, more commonly), Pabst opted here for grubby authenticity; if you happened to stumble upon the remains of Atlantis hidden in the Tunisian interior, chances are it really would look a lot like this. The believable setting acts in curious dissonance with Pabst’s ethereal style, playing up the disorientation that is so central to the movie’s success. It seems almost like an accident, though, so I’d be very curious to compare this version to its Continental sisters if ever the opportunity arose.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact