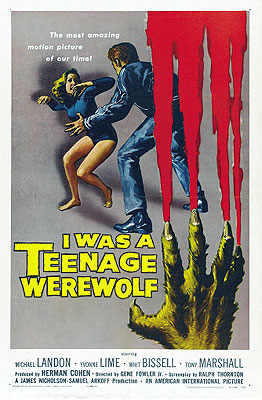

I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) **

I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) **

This is the movie that secured American International Pictures’ place at the top of the B-movie heap in the late 1950’s, adding mastery of the horror genre to the list of the studio’s conquests. The secret to I Was a Teenage Werewolf’s success-- and, by extension, that of AIP as a whole-- was that it was aimed explicitly at the teen audience. Today, this idea is old hat; nearly every horror movie of the past 40 years was pitched, at least to some significant extent, at teens, and it is easy to get the impression that it was ever thus-- especially when we’re talking about B-horror movies. But, while it is almost certainly true that the youth market has always been the primary consumer of such films, think about how many teenage characters you see in the movies themselves before 1957. There are no teenagers in It Conquered the World, Earth vs. The Flying Saucers, or Tarantula, and those teenagers that do appear in, say, The She-Creature are of decidedly secondary importance to the story. Children have a major role in Invaders from Mars, it is true, but as anyone who’s ever lived with one will tell you, there is a world of difference between a child and an adolescent. After 1957, on the other hand-- that is to say, after I Was a Teenage Werewolf-- the floodgates had opened: I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, Invasion of the Saucer Men, Teenagers from Outer Space, Earth vs. The Spider, The Giant Gila Monster, and countless others swarmed forth to join the hundreds of juvenile delinquent films, rock and roll movies, and all those awful beach party flicks. And this is the one that started it all.

Like most firsts, I Was a Teenage Werewolf hasn’t aged particularly well. The first part of the movie does quite a good job of setting everything up in an engaging and economical way, but this flick doesn’t really know what to do with its monster, and that is pretty much the kiss of death for a horror movie. This film is saved from true dreadfulness only because the titular werewolf is really only the secondary agent of evil here. The movie uses the threadbare 40’s approach of making the central character the werewolf, combining the roles of villain and victim in a single character. Unlike in The Wolf Man, however, the werewolfery in this film is entirely free of supernatural trappings, and is instead the product of that most characteristically 50’s force for chaos, Science Run Amok.

Tony Rivers (High School Confidential’s Michael Landon), you see, is a troubled boy. He’s basically a good kid, but he has an explosive temper and seems constitutionally incapable of compromise. Thus he spends much of his time getting into fights with his classmates-- even with his close friends. In fact, the very first scene of I Was a Teenage Werewolf has Tony embroiled in a raging fist-fight with another boy who must outweigh him by about 75%. We know that this is not the usual schoolyard altercation when Tony (who is of course on the fast track to defeat) picks up a nearby shovel to use as a weapon. It takes the appearance of a policeman (Barney Phillips) to stop the fight, and as the cop listens to both boys explain what happened, we discover that there was really no motive worthy of the name, and that Tony turned on the larger boy for essentially no reason. And it turns out that this is by no means the first time that this particular cop has had to break up a fight in which Tony was involved. In the inevitable Stern Talking-To that results, the policeman suggests to Tony that he see a local psychologist named Dr. Brandon (Whit Bissell, of Monster on the Campus and Creature from the Black Lagoon), who specializes in the psychology of aggression, and who might be able to help Tony control his rage. Tony, of course, is not interested.

What it takes to convince him is a scene that he causes at a Halloween party, in which, after playing several harmless pranks himself, he attacks one of his friends who pulls a similar trick on him. His girlfriend Arlene (Yvonne Lime, from Dragstrip Riot and Untamed Youth) had actually talked to him about seeing Dr. Brandon earlier that night. At the time, Tony admitted that he had a problem, but he insisted that he was able to take care of it “his way.” After the party, it’s fairly obvious that “his way” is of no practical use, and that professional help is almost certainly necessary. Such a shame, then, that the nearest provider of such help proves to be an archetypical mad scientist, obsessed with some crackpot notion that the human race will destroy itself within a matter of years if it does not regress to a primitive state and rebuild from the ground up. When Dr. Brandon meets Tony, he sees in the boy exactly the sort of atavistic personality that he has been looking for as an experimental subject. What Brandon essentially proposes to do is use a combination of drugs and hypnosis to get Tony in touch with his inner australopithecine. As you might have guessed on the basis of the movie’s title, the actual effect is to transform Tony into something that closely resembles the werewolves of European folklore.

Fortunately for the town, the janitor at the police station (Vladimir Sokoloff, from Mr. Sardonicus and Monster from Green Hell) is a Romanian, and he recognizes the marks on the bodies when Tony starts killing. No one believes him at first, naturally, but Tony’s second lycanthropic seizure causes him to attack a girl practicing her gymnastics routine after school, and he is seen and identified by a number of people, including his principal. All of these inform the police that, though the girl’s assailant was definitely Tony, he scarcely seemed human-- he was fanged and furry, and seemed to possess superhuman strength and agility.

What follows is an overly long and wholly uninteresting sweep of the nearby forest, in which large numbers of policemen wander around in the woods while Tony hides under bushes. The closest thing to excitement that this scene has to offer is a fight between Tony and a German shepherd (Tony wins), which is marred by the use of an extremely obvious dummy dog in the shots where Tony’s face is visible. (That the dummy dog isn’t even the right color is clear, even in black and white.) The inevitable confrontation between Brandon and Wolf-Tony is only slightly better, consisting mostly of Tony knocking over the doctor’s Florence flasks and Bunsen burners while staring Brandon down.

It’s true, I wouldn’t go so far as to call I Was a Teenage Werewolf an outright bad movie, but it had a distinctly hard time holding my interest. The film relies too much on the raw fact of the monster’s existence as its driving force, an approach that might have been viable many decades ago, but which seems insufficiently aggressive even by 50’s standards. Not only does the werewolf take its sweet time showing up, once it appears, it just doesn’t do much. Were it not for Dr. Brandon, a far more active agent of evil, the movie would have had nothing at all to threaten its characters with. The mistakes aren’t severe enough to be lethal, but they still take an awful lot out of the film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact