The She-Creature (1956) -*½

The She-Creature (1956) -*½

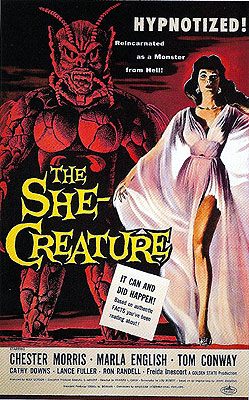

Paul Blaisdell is a misunderstood genius. Throughout the latter half of the 50’s, it was his remarkable mind that spawned the bulk of American International Pictures’ unforgettably daffy rubber monsters-- atomic mutants, squash-headed aliens with extra eyes on the backs of their hands, megalomaniacal six-foot carrots from the planet Venus, Beasts with a Million Eyes-- and he did so on budgets that not even such legendary skinflints as Roger Corman and Samuel Z. Arkoff could complain about. In 1956, when A.I.P. honcho Arkoff got it into his head to make a movie that would rip off Svengali, The Search for Bridie Murphy, and Universal International’s gill-man trilogy all at the same time, Blaisdell was the obvious man for the job of creating the monster. Holy shit, did he ever outdo himself! Arkoff had asked for a gill-woman to one-up Universal’s gill-man. What Blaisdell came up with was the only American movie monster I know of that matches the wild, hallucinatory inventiveness of a late-60’s Japanese kaiju suit; you could drop this critter into an episode of “Ultraman Leo” and nobody would even notice. The She-Creature is much less fishy than Creature from the Black Lagoon’s archetypal gill-man, resembling nothing so much as a cross between a lobster, a lizard, and a professional wrestler, with spikes protruding from all its joints, and fan-shaped fins scattered seemingly at random around its body. It’s about as unfeminine a beast as can be imagined, but Blaisdell seems to have figured that we’d get the point if he added a few conspicuous, feminizing details: a pair of majestically titanic, armor-plated tits and (of all things) a blonde wig! (Some commentators contend that the wig was added when the monster suit was reused in Voodoo Woman a bit less than a year later, but look closely, and you’ll see that it’s already in place in The She-Creature. I suspect the reason so many people miss the wig here is that it’s much less bulky than the Voodoo Woman wig, and it remains soaked to the monster’s scalp throughout the entire movie-- Paul Blaisdell was, in his way, a perfectionist, and if authenticity seemed to demand that his monster have wet hair, by God it would, even when the rest of the thing’s body is bone-dry.) It really is a pity that, in order to see such an astonishing monster, it is necessary to sit through such an agonizingly dull movie.

The She-Creature gets off to a fairly respectable start, with carnival sideshow mystic Dr. Carlo Lombardi (Chester Morris, of The Bat Whispers, who played the title character in all the zillions of “Boston Blackie” crime movies) standing on a beach, gazing into the waves as he talks mysteriously to himself about having “summoned her forth from the depths of time,” and how, now that he has done so, “nothing and no one, man nor animal, will ever be the same.” The next fifteen minutes use a surprisingly sophisticated layered storytelling technique to introduce us to the remainder of the major characters and explain their relationships to each other and to Dr. Lombardi, while simultaneously establishing the latter’s credentials as the movie’s main villain. Dr. Ted Erickson (This Island Earth’s Lance Fuller, who would square off against this movie’s monster suit again in Voodoo Woman) is a psychic researcher (or so we are told-- all we ever get to see of his “research” is the ever-popular shot of him gazing thoughtfully at a Florence flask full of dyed water and taking unexplained notes on a bunch of caged white rats) whose main field of interest seems to be the debunking of Lombardi’s ideas. Dorothy Chappel (Cathy Downs, who later played The Amazing Colossal Man’s put-upon fiancee) is a stuck-up rich girl who would very much like to get into Erickson’s pants now that she’s finally managed to rid herself of her alcoholic boyfriend. Timothy Chappel (Tim Conway, from Cat People and Bride of the Gorilla) is Dorothy’s tycoon father, whose credulous wife (Frieda Inescort, from The Alligator People and The Return of the Vampire) is a follower of all things occult and an adherent of Lombardi’s. After leaving a party at the Chappel mansion, Erickson and Dorothy go for a walk on what turns out to be the same beach where we saw Lombardi watching the surf earlier. The strolling couple see Lombardi leaving a beach house they know very well does not belong to him, and when they go to investigate, they find its owners dead, their necks snapped as though (in one of The She-Creature’s favorite descriptive phrases-- it comes up again and again) “they had been hit with a pile-driver.” Erickson calls Lieutenant Ed James (Captive Women’s Ron Randell), the worst detective in California, to report the deaths, and after a brief period of roaming around the cottage wiping his un-gloved hands all over everything that could be at all useful as evidence, he asks Erickson if he would be willing to swear for the record that he saw Lombardi leave the crime scene. The soggy footprint on the living room carpet may not look like anything made by a man (unless, of course, that man were wearing a large, rubber monster suit), but the detective is certain Lombardi is to blame.

And so ensues Lombardi’s first encounter with Lt. James. The detective and the scientist track Lombardi down at the carnival where he works, passing by a poster that advertises his act. Wow. That’s some act. He’s got prognostication, hypnosis, reincarnation, transmigration of the soul, the materialization of the spirit, past-life regression, and at least four or five kitchen sinks, all leavened with the most vital element of any two-bit spectacle: T&A. The T&A in this case is provided by his assistant Andrea (Marla English, another face we’ll be seeing again in Voodoo Woman), who spends easily half her screen time wearing absolutely the most transparent dress that it was possible to get away with in 1956. Her role is to lie on a bench looking sexy while Lombardi hypnotizes her and regresses her into identities she’d had during previous lifetimes. He then gives these prior personalities “substance, but not form,” and makes them do tricks like drawing curtains and opening windows on the other side of the room. And while all that is going on, Lombardi throws in predictions to the effect that within the next [insert timeframe of your choice], an ancient sea creature that was the original incarnation of someone living today will come ashore to commit a murder or two. It’s that last part that has James thinking Lombardi’s behind the deaths at the beach house. He figures Lombardi, either in person or acting through hired thugs, killed the cottage couple to inflate his reputation on the sideshow circuit by substantiating his clearly ridiculous predictions about homicidal Cambrian sea-monsters. When Erickson identifies Lombardi as the man he saw leaving the beach house, James places him under arrest (not for the last time, either) and takes him to the police station for the first of many wholly fruitless interrogations.

This scene is also the point at which Erickson meets Andrea, for whose sake he will turn his back on his budding but unsatisfying relationship with Dorothy. We’re supposed to think this is because her unaffected simplicity, down-to-Earth charm, and compassion-inspiring vulnerability make an alluring contrast with Dorothy’s snobbery, materialism, and grating air of personal entitlement, but it’s obvious what Erickson’s true motives are from the moment he first lays eyes on Andrea. Look closely at the reaction shot of Erickson that follows his introduction to the young woman; notice that his gaze is riveted on the precise spot where Andrea’s tits would be if she were in the shot. If you think that’s not a leer, you don’t know the meaning of the word. But whatever its basis, a close relationship with a man other than Lombardi is exactly what Andrea needs at the moment. As the sinister mystic spends so much of the movie’s running time asserting, Andrea is completely in thrall to the man, whose great hypnotic powers, combined with her unusual susceptibility to the process, enable him to make her do absolutely anything he wants. Anything, that is, except what he would really like her to do, which is of course to fall in love with him. Because Erickson is a hypnotist too, Andrea hopes that he will be able to help her break free of Lombardi’s hold.

Which doesn’t really bring us to Timothy Chappel, but we need to get around to him somehow, and this seems as good a time to do so as any. Chappel has decided that Lombardi is a goldmine waiting to be tapped by someone with the savvy to exploit him properly. Chappel goes to the occultist with an utterly ingenious scheme. Lombardi will begin making personal appearances to perform at the Chappel mansion to generate what no one had yet thought to call “buzz” in 1956. Using this new notoriety as a springboard, Lombardi will then employ Chappel’s enviable network of connections to get himself bookings at big, prestigious venues around the country. And Chappel has even figured out how to use Erickson to his and Lombardi’s advantage. If possible, Chappel will bribe Erickson to endorse Lombardi; if not, he will see to it that Erickson puts in an appearance at as many of Lombardi’s in-house performances as he can work into his schedule to try to discredit him-- after all, negative publicity is often the most effective kind. All Chappel wants in return is 50% of the profits from the venture. Lombardi signs on, and as soon as Chappel’s lawyer gets him out of James’s jail for what is now at least the second time, he plays his first gig at the mansion, where he makes another prediction that the sea monster will attack, and indeed will do so that very night.

By this time, I’m sure you’ve figured out that the “someone living today” of whom the creature is the original incarnation is Andrea. It is for this reason that, try as he might, Lombardi can’t seem to get it to kill Erickson, whom he’d really like to have out of the way. The beach-house couple-- fine. The nosy fellow carnie who becomes suspicious at the amount of time that Lombardi keeps Andrea under deep hypnosis-- no problem. A pair of necking teenagers in an early-40’s Ford-- of course. But not Erickson. Lombardi’s determination to have the other hypnotist done away with only increases when a clinical trial of Lombardi’s powers convinces Erickson that there may be something to the man after all, but no amount of determination will sway the obstinate lobster girl, who ultimately ends up slaying-- big surprise-- Lombardi instead. Lombardi repents his cruelty moments before he dies, and with his last breath, he releases Andrea from his hold, somehow using his powers to set up a barrier in her mind that will make her henceforth no more susceptible to hypnosis than the average woman. Pay no attention to that question-mark that fills the screen in the last shot; this really is the end.

And if you glance quickly at the clock, you’ll see that only an hour and 22 minutes have passed, as opposed to the week and a half you were sure you’d spent watching this clunker. The more I think about it, the bigger a shame it seems to be that director Edward Cahn put so little energy into this project. Above and beyond the obvious allure of the monster, and the slightly less obvious allure of a movie that attempts to milk simultaneously every single aspect of the mid-50’s quack spiritualism fad while also ripping off Creature from the Black Lagoon, there are also a couple of interesting ideas being explored with the surprisingly complex character of Dr. Lombardi. To begin with, there’s the unexpectedly plausible love-hate relationship he has with Andrea, which is especially intriguing in that his unrequited affection for her ultimately triumphs over the sadism into which it had been channeled throughout the film. But even more remarkable is his relationship with Chappel. We expect Lombardi to be a good little evil genius and insist at the top of his lungs that his crackpot ideas are well-founded at every opportunity, and most of the time, this is exactly what Lombardi does. And of course, he really does know what he’s talking about, even if it kills him in the end. But when he’s around Chappel, Lombardi is perfectly willing to pretend to be the charlatan Chappel believes he is. Lombardi may be a madman, but he’s sane enough to know which side his bread is buttered on, and to tell his benefactor exactly what he wants to hear, whenever he wants to hear it. You have to wonder how so elaborately drawn a character wound up in a movie otherwise populated by only the flattest of stereotypes, right down to an all-but-unendurable pair of comic-relief domestics whose entire existence in the film is predicated on the supposedly funny fact that Swedes pronounce “j” like an English “y.” (The lengths to which this movie goes to put “j”-words into the mouths of these two are nothing short of shameful.) Unfortunately, Cahn’s listless direction makes it even harder to appreciate Lombardi’s complexity than it is to appreciate what ought to be he hilarity attendant on the blonde-haired, torpedo-breasted lobster woman and her lumbering attacks on characters who are obliged by her sloth to stop fleeing periodically in order to give her a chance to catch up. It’s enough to make me wonder if A.I.P.’s frequent re-use of The She-Creature’s monster (at least part of her shows up in at least three other films) had anything to do with Paul Blaisdell wanting to give her a movie that was worthy of her.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact