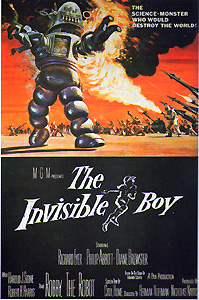

The Invisible Boy/Spaceship S.O.S. (1957) **½

The Invisible Boy/Spaceship S.O.S. (1957) **½

This fitfully entertaining late-50’s oddity enjoys the distinction of being one of the more inaptly named movies I’ve seen in a good long while. With a title like The Invisible Boy, you’d probably expect a kiddie matinee variation on the venerable H. G. Wells novel, while Spaceship S.O.S. suggests something along the lines of the later Marooned. In fact, what we have here plays more like a hybrid of Tobor the Great and a family-friendly version of Colossus: The Forbin Project.

Dr. Tom Merrinoe (Philip Abbott, later of Hangar 18 and The First Power) is the head scientist at the Stoneman Institute of Mathematics. His is the brilliant mind behind the institute’s pride and joy, a typically gargantuan 50’s-style computer, complete with dozens of erratically rotating reel-to-real tape drives and countless thousands of tiny, flickering lights. One day, an air force officer named General Swayne (Harold Stone, from X! and The Werewolf of Woodstock) comes to the institute to use Merrinoe’s machine. Swayne’s unit has finally developed a workable transatmospheric rocket, and he wants to run one last check on the calculations central to its impending launch. As it happens, the current estimates of the amount of fuel necessary for the mission are off by an alarming 29%. Having made that check, the general has another question for the computer: how does it rate the likelihood of “our friends across the pole” launching a nuclear attack on the United States in the event that their spies get wind of the rocket program? The computer figures on a 65% chance of a nuclear offensive if the Russians learn about the rocket before the launch (that is to say, while there’s still a chance to do something about it), but says a successful launch of the vehicle prior to word reaching the Kremlin will drop those odds down to a mere 13% or so. (The idea presumably being that if we’ve got one rocket, we could just as easily have a whole arsenal of the things, while a missile that can achieve sustained orbit should be equally capable of reaching the Soviet Union with a couple dozen megatons of thermonuclear goodness.) Satisfied with these answers, the general goes on about his regular business.

Skip ahead a few hours to the early evening, and shift the locale to the Merrinoe house. Professor Merrinoe’s family life is, or so it would appear, not quite what he might once have hoped. His wife, Mary (Diane Brewster, of Pharaoh’s Curse), seems awfully tedious, but then men apparently liked their women boring in those days, so perhaps it doesn’t really matter. Merrinoe’s son, Timmy (Richard Eyer, who also played the juvenile genie in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad), on the other hand, is indubitably a disappointment to his old man. Far from taking after his intellectual father, Timmy is a dullard just like Mom. Particularly frustrating to the professor is Timmy’s helplessness in the face of Merrinoe’s two great passions, mathematics and chess. At his wits’ end, Merrinoe gets it into his head that maybe the computer might be able to set the boy straight. The next day, he brings his son to work and leaves him with the machine for several hours. As per Merrinoe’s secret instructions, the computer hypnotizes Timmy, and then attempts to impart a vast amount of learning to him by way of hypnotic suggestion. And remarkably enough, the effort pays off. Not only does the boy come out of his session with the machine a full-on chess wizard, he also becomes a technical thinker of no small talent. That night, Timmy tricks his dad into granting him “anything he wants” in the event that he can beat Merrinoe at chess, and then proceeds to mop the floor with him in all of six moves. Simultaneously proud and chagrined, the professor consents to let Timmie have his wish— to play with Robby the next day.

Who’s Robby, you ask? Why, Robby is a robot that was invented by a former colleague of Merrinoe’s (now deceased), which has sat in dismantled condition in the institute’s junk room for many years, defeating all the best efforts of Merrinoe and the other scientists to put it together. (There is some indication that the dead professor brought Robby back from the future after perfecting an experimental time machine, but nothing much is made of this angle.) And in case you couldn’t guess, this is the very same Robby the Robot which we previously saw lumbering around the Morbius homestead on Altair IV in Forbidden Planet. The computer’s hypnotic lesson plan proves to be every bit as effective a pedagogical tool as that movie’s Krell brain-booster machine, and Timmy now has the smarts to put Robby together in just a couple of hours. Adopting the ambulatory machine as a sort of high-tech pet, Timmy goes home and begins getting into all manner of advanced mischief, a cause which is furthered when the boy brings Robby to the computer to have its primary directives rewritten so as to disable the robot’s programming against permitting risks to human safety.

The fun and games stop, however, when Mary Merrinoe catches her son riding aboard the gigantic kite built for him by the robot. Timmy expresses his wish that his mother wouldn’t always be around to catch him when he does that sort of thing, and Robby unexpectedly suggests a practical solution to the problem. If Robby were to alter the boy’s “coefficient of refraction,” Timmy would become invisible, and would thus never have to worry about being caught again. Timmy thinks this is a great idea, and has his mechanical playmate render him transparent that very afternoon.

You’ve got to wonder why Dr. Merrinoe has an invisibility machine just lying around in the garage. For that matter, you’ve also got to wonder how Timmy’s parents can possibly be so blasé about the idea that their son has gone and turned himself invisible somehow— Merrinoe even goes so far as to say that the boy is probably only doing it to get attention! Whatever the reason for their stoicism, the Merrinoes draw the line at being spied on in their bedroom, and when the invisible Timmy interrupts them while they’re trying to get all Barry White on each other, it does not go well for him. In the aftermath of the ensuing punishment, Timmy runs through the usual litany of childhood escape fantasies— running away to Australia and such— within earshot of Robby, and again the robot makes a suggestion. Forget Australia, he says; with Robby’s help, Timmy could run away to the Moon!

There’s something more sinister going on here than a misbehaving child and his overly helpful droid companion, though. As Merrinoe is about to discover, that computer down in the institute’s lowest subbasement has developed authentic autonomous intelligence. In fact, the machine has been a thinking, sentient being for years, and this whole strange business about making Timmy smart enough to get Robby up and running has been part of an elaborate blackmail plot. Now that Timmy is invisible and Robby has been reprogrammed so as to be able to harm humans, the computer instructs the robot to bring Timmy to the launch site of General Swayne’s rocket, whence he can be sent into orbit as the ultimate hostage. Meanwhile, Robby will also be making the rounds of Swayne’s colleagues— and Merrinoe’s too— implanting them with remote mind-control devices. With damn near everyone in authority at the institute and the rocket base doing the computer’s bidding, and with Merrinoe’s son safely in its digital clutches, it ought to be a simple matter for the computer to extort a particular bit of data from its creator— the numerical code that will disable its own built-in anti-theft system. Then the computer can have Robby load it onto Swayne’s rockets one piece at a time, launch it into orbit, and reassemble it in a place where it will be impervious to virtually any practicable form of attack. (This plan presumably also explains why the computer told General Swayne that his rocket needed 29% more fuel than anticipated.) From its unassailable new position, the computer will then be able to exterminate all organic life on Earth, and repopulate the planet with mechanical organisms like Robby and itself. The only flaws in the computer’s scheme are that Dr. Merrinoe has figured out exactly which upgrades were responsible for giving his creation consciousness, while nothing in a film of this vintage— not even a robot— can long resist the charm of a precocious child.

No doubt about it, The Invisible Boy is aimed mainly at an audience not appreciably older than its title character. Nevertheless, its creators did at least expend some effort to make it palatable to its target audience’s parents, who were, let’s face it, likely to be roped into going to see it too. Timmy ends up being little more than a background character for the movie’s final 30 minutes or thereabouts, while the menace posed by Merrinoe’s renegade computer is of a rather more adult quality that might be expected. There are some major logical inconsistencies, to be sure, but this mad computer makes much more sense than most of its inexplicably human-like fellows. Meanwhile, there are some interesting things going on in the relationship between Timmy and his parents that I can’t believe are mere accidents. The older Merrinoes’ unflappable calm in the face of such bizarre developments as their unexceptional son turning into a genius overnight, acquiring a seemingly all-powerful mechanical playmate, and even becoming invisible plays like a deliberate satire of the omniscient parental figures familiar from contemporary television shows, though the low-key handling of it all makes it difficult to be certain one way or the other. The portrayal of the other adult characters also seems calculated to wring a knowing smile out of grownups who have sat through a decade’s worth of cheap-ass monster movies in the company of their monster-loving children. General Swayne especially seems to be a milder form of the military caricature that Stanley Kubrick overplayed to such striking effect in Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. None of these angles are played out sufficiently to make The Invisible Boy much more than a passable B-grade matinee movie, but they do keep it from wearing out its welcome before the closing credits.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact