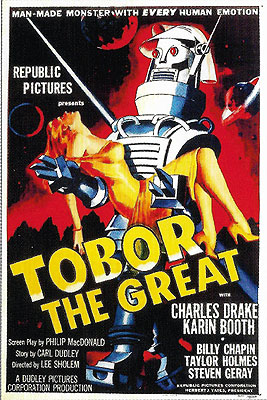

Tobor the Great (1954) **

Tobor the Great (1954) **

This one was a bit of a disappointment. This mid-50’s sci-fi kiddie flick could have been something special, what with its intriguing mix of boy geniuses, communist spies, daffy old scientists, clunky robots, and endless stock footage. But alas, Tobor the Great is neither bad enough nor twisted enough to live up to its potential.

Dr. Ralph Harrison (Charles Drake, of It Came from Outer Space and The Screaming Woman) is a rocket scientist hard at work on the problems of manned space flight— an endeavor which in this case entails showing us exactly the same stock footage of post-war test launches of captured V-2 ballistic missiles over and over and OVER AGAIN!!!! The commissioner of the space agency for which Harrison works (Norman Field, from Them! and The Twonky) is determined to send a man into space at the earliest opportunity, regardless of the risks. (Remember, in 1954, even the most up-to-date scientific thinking about the conditions prevailing in outer space amounted to little more than educated guesswork.) Harrison, on the other hand, finds the commissioner’s cavalier attitude toward the lives of his test pilots to be nothing short of disgraceful. After a particularly fierce row with the commissioner, Harrison tenders his resignation, and storms out of the office, the building, and the project as a whole.

In the days following his explosive exit, Harrison is plagued by reporters who want to know what all the hubbub is about. In the midst of fighting off the journalists, Harrison receives a phone call from a Dr. Arnold Nordstrom (Taylor Holmes), head scientist at the space agency. Dr. Nordstrom, it turns out, is just as disgusted by the commissioner’s rush to put men into space as Harrison is, only Nordstrom thinks he has found a viable alternative that might still keep the project on schedule if it can be perfected soon enough. And with Harrison’s help, or so Nordstrom says, that “might” would surely become a “will.” Harrison, happy to finally hear from someone who sees things his way, agrees to do whatever he can.

With that in mind, he and Nordstrom fly out to California, where the older scientist’s home (and secret laboratory) is located. (Nordstrom’s house, by the way, has all the amenities one would expect in a dwelling that conceals a slightly mad lab— electrified fences, infrared security cameras, everything but a squad of bloodthirsty robot monkeys.) Nordstrom introduces Harrison to his family— widowed obligatory love-interest daughter Janice (Karin Booth) and child prodigy grandson Brian (Night of the Hunter’s Billy Chapin)— and then takes him down to the basement to show off his creation. This, as you might have guessed, is Tobor. Tobor is a seven-foot robot (Hey, that’s “Tobor” spelled backwards!) which seems to have been made out of whatever metallic junk happened to be lying around the studio when production on this movie started. Being a machine, Tobor needn’t worry about such trifling concerns as cosmic rays or excessive G-forces. With it at the controls, the space agency’s rockets can be tested to their very limits without ever endangering a human life, while essential data about the actual conditions to be found in space can be collected on an equally risk-free basis. But the truly amazing thing about Tobor is that it is more than just a machine. Its “brain” has been designed to mimic the full range of human emotion, a feature which Nordstrom thinks will be advantageous from an adaptability perspective. If Tobor is capable of experiencing fear, or unease, or anger, it will be far more likely to respond to emergent situations in such a way as to maximize the chances of its— and its spaceship’s— survival. And if it is capable of affection, it will be far more useful at such time as it becomes possible for humans to join it on its missions— future astronauts are sure to appreciate having a huge, super-strong robot around with an innate drive to protect them from danger. And as the final touch, Tobor can be controlled directly by human brainwaves.

With two accomplished scientists on the case, it isn’t long before Tobor is ready for its great unveiling. Knowing full well what a stick in the mud the space agency’s commissioner is, Nordstrom and Harrison decide to make that unveiling to the press, rather than to the commissioner’s bureaucrats. They invite reporters from twelve distinguished newspapers to come to Nordstrom’s place for a press conference, wowing the lot of them with Tobor’s capabilities. There’s just one problem, though. After the journalists leave, Harrison notices that there are thirteen empty chairs set up in the basement. Thirteen chairs, twelve reporters... Oh shit! Communists!!!! Damn straight. The dirty red spy (Steven Geray of Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter) gets right to work trying to figure out a way to steal Tobor, or at least the secrets of its creation and control. When his attempts to sneak into the house fail, he changes tack and tricks Nordstrom and Brian into going to see a non-existent show at the nearby planetarium. Nordstrom and the boy fall into the spy’s clutches just hours before the doctor was to present the more or less perfected Tobor to a committee of politicians, generals, and space agency apparatchiks, and when they fail to return on schedule, Harrison and Janice just about lose their shit. Fortunately for everyone, Nordstrom is wearing Tobor’s control rig, which conveniently resembles an early-50’s hearing aid, and he is able to con the spy and his henchmen into letting him turn the thing on. Then it’s Tobor to the rescue, and a big round of happily-ever-afters for everybody but those lousy, stinking reds.

Sounds like fun, doesn’t it? The problem is that it’s handled in such a way as to be actually quite dull. Only when the incredibly shitty robot is on the screen does Tobor the Great have any real life to it, and Tobor’s screen time is unfortunately rather limited. More of Tobor lumbering about doing whatever would have paid great dividends. Or if less time had been spent on perfecting the usually inanimate robot and more on the activities of the communist agents, this might also have made Tobor the Great more than just a middling juvenile fantasy film. But the filmmakers did neither of those things, and middling juvenile fantasy is exactly what we get.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact