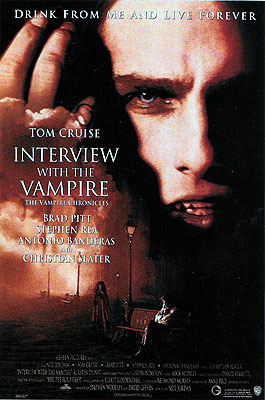

Interview with the Vampire/Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles (1994) **

Interview with the Vampire/Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles (1994) **

All movies must pass through a vast and perilous wilderness on their journey from the preliminary safe haven of the Option Agreement to the promised land of General Release. And in all that wilderness, the greatest and most fearful peril is the bottomless, sucking void known as Development Hell. Many a project has vanished into Development Hell never to return, and of those films that escaped it, few have ever come out in a form recognizable to those who knew them before they went in. Escapees from Development Hell emerge with new producers, new directors, new casts; different studios, different scripts, different titles. The most extreme unfortunates may have even their very genres altered during their sojourns on the other side. Nor is there any sure talisman against being sucked in and entrapped. The mightiest studios and the most rinky-dink, the most beloved stars and the most obscure nobodies, the most desireable pre-sold source material and the least assuming original screenplay— they’ve all been attached to projects that wandered Development Hell for years, and to others that were irretrievably lost to the void.

Consider the case of Interview with the Vampire. The folks at Paramount were so excited by the cinematic potential of Anne Rice’s novel of the same name (which, much as I loathe it, legitimately was a groundbreaking work, creating an entire new subfield of vampire fiction) that they bought the film rights in April of 1976, before it was even published. The book was a strong and perennial success, and gained steadily in readership, influence, and visibility over the next decade and a half, as Rice cranked out sequels, prequels, and spinoffs in impressive profusion. And yet throughout all those years, the movie never quite managed to come out, despite having some of the biggest names in Hollywood attached to it at various points during its gestation. Paramount sold Interview with the Vampire to Lorimar, who sold it in turn to Warner Brothers. One set of stars after another aged into and out of the roles reserved for them. Script draft followed script draft, including versions with one or both of the pivotal characters gender-flipped. And in the end, it seems to have taken the announcement that Francis Ford Coppola was making a Dracula picture for Columbia to give Interview with the Vampire the impetus needed to achieve escape velocity. (Even then, Warner Brothers cautiously held up production until Bram Stoker’s Dracula had proven itself at the box office.)

A shady-looking guy called Malloy (Christian Slater, of Hollow Man II and Tales from the Darkside: The Movie) has been following a seemingly in-no-way-interesting pretty boy (Brad Pitt, from Seven and Troy) around the streets of New Orleans for some considerable while. His pursuit is finally rewarded when his quarry enters a rowhouse, and carelessly leaves the front door unlocked behind him. There’s no crime in the offing here, whatever the situation may look like (unless you count a few against Reason which the screenwriters will commit during the coming two hours). Rather, Malloy has chased Mr. Boringly Beautiful all over Hell’s creation because he unaccountably wants to interview him. Evidently that’s just what this schmuck does, whether professionally or as the world’s most irritating hobby. Luckily for Malloy, Louis (to give this refugee from a Johanna Lindsey paperback cover his proper name) does indeed have a story to tell, for Louis is a genuine, not-fucking-around vampire. Here— watch him zip around the room at superhuman speed if you don’t believe him!

Louis says he became a vampire in 1791; before that, he was a New Orleans indigo planter. That was before the Louisiana Purchase, so he was also technically French back then. Anyway, it was a low point in Louis’s life. His wife and child had died of some grotesque disease, and he could find no more meaning in existence without them. He became a championship-level wastrel, drinking, gambling, and whoring to great excess, squandering his fortune as rapidly as he could, and mismanaging his plantation into the ground. He also developed a habit of picking fights with the roughest of ruffians, in the hope that eventually one of them would go far enough to kill him. In the end, though, Louis was slain not by any brawler, pimp, or cutpurse, but by an undead aristocrat by the name of Lestat (Tom Cruise, from Edge of Tomorrow and Legend). Mind you, Lestat didn’t do it all at once. His first attack left Louis merely on the brink of death, at which point the vampire purred to him, “I’m going to give you the choice that I never had.” Remember that, as Louis mopes and moans and pules his way through the rest of this movie. When a monster offered him the annihilation he so craved, Louis chose instead to become a monster himself, and to acquire while he was at it an infinite supply of the life that he claimed to be thoroughly sick of.

Louis goes on to describe the education in supernatural murder which he received from Lestat, together with the moral anguish that he performatively suffered each time the elder vampire took human life on their shared behalf. He tells of the fear which spread among his slaves, including even his beloved housekeeper, Yvette (Solo: A Star Wars Story’s Thandie Newton), who alone among the people of the city were prepared to admit to themselves what their master and his peculiar friend really were. He recounts how he attempted to reconcile himself to his vampirism in the most hideous possible way, by draining the blood of a little plague orphan called Claudia (Kirsten Dunst, of Midnight Special and The Beguiled)— and how Lestat multiplied the evil of his crime a hundredfold by resurrecting the child as a vampire. He further explains that as the decades wore on, Claudia become the most perverse and hateful and twisted of the trio, trapped forever as she was in her immature body, no matter how much time and experience deepened and sharpened her mind. That became the undoing of Louis’s little undead family, in fact, for Claudia rightly came to detest her elders— Lestat most of all. Louis talks about the fateful night when Claudia tried to destroy Lestat by treachery, and about how her markedly incomplete success forced her and Louis into hiding in Paris. That was where they joined the court of Armand (Antonio Banderas, from The 13th Warrior and The Skin I Live In), who claimed to be the world’s oldest surviving vampire, and whose followers used to hide in plain sight by operating a Grand Guignol-style theater in which their very real killings were passed off as ghoulish stage entertainments. But most of all, Louis reveals a melodramatic habit of burning down his domiciles whenever things go badly for him: first the plantation house in a transport of moral despair over his condition; then the mansion where he, Lestat, and Claudia rang in the 19th century, which fell as collateral damage in the aftermath of Claudia’s botched attempt at patricide; and finally the Theatre des Vampires, in revenge for the inmates’ treatment of Claudia. Finally, as Louis brings his story into the 20th century, it becomes increasingly obvious that a side effect of the vampire’s changeless immortality is a constitutional inability to learn from his mistakes. It’s even possible that that’s the intended point of the film.

Remarkably enough, I’ve been able to find no close accounting of what kept Interview with the Vampire in Development Hell for so long, even a quarter of a century after its release. My first instinct is to blame homophobia, since the novel is only marginally less queer than Rice’s extravagantly pansexual Sleeping Beauty trilogy, and the film that finally emerged, although toned down quite a bit in that department, still comfortably clears the minimum threshold for “gay as fuck.” Reports of script drafts featuring female versions of Lestat or Louis would tend to support that reading— as might, in a sidelong way, reports of at least one draft in which both central vampires were women. After all, modern Western culture has a weird and not exactly proud tradition of treating lesbianism as somehow more acceptable than male homosexuality. I’m not sure it’s that simple, though. I mean, I remember 1994. The cultural environment was less hostile for minority sexualities than it had been ten years earlier, but the struggle for gay acceptance still had a lot of uphill miles ahead of it. A tale of bad love between undead dudes still seems like a risky bet for a would-be blockbuster in the mid-90’s, if that had indeed been the stumbling block in the mid-70’s or mid-80’s. On the other hand, Interview with the Vampire ended up with Tom Cruise— an actor notoriously jealous of his heterosexual bona fides— in by far the queerer of its two starring roles. So maybe we should be looking elsewhere for the reason why it took this movie eighteen years to find its way to the screen. Or perhaps it was simply that Rice (the credited screenwriter for the finished version) and director Neil Jordan (who reworked Rice’s script extensively) managed to devise a take on the material stealthy enough to slip past the less sensitive gaydar that most straight Americans were packing 25 years ago. I can say, though, from personal experience, that Interview with a Vampire’s queer content was conspicuous enough at the time to be noticed by a college-age kid consciously in the process of figuring out the parameters of his own sexuality.

Okay, so Interview with the Vampire was useful to me developmentally in 1994, but is it good? Sad to say, not really. The movie’s central defect is its viewpoint character. Louis is almost totally reactive, even in circumstances where the stakes are literally eternal, and the choices he makes once he’s finally pushed into doing something are almost always self-evidently bad and dumb. Furthermore, it doesn’t take long before one notices that the one consistent feature of Louis’s behavior is that he invariably opts to maximize his potential for future self-pity. In that respect, his reaction to being attacked by Lestat is virtually his manifesto: given a chance to end his supposedly unbearable existence, Louis passes it up in favor of a chance to go on sulking forever. Even his most dramatic action— the conflagration of vengeance which he exacts upon Armand’s followers— he carries out in such a way as to leave himself unsatisfied with the outcome. It would be one thing if all this passive suffering and reactive self-sabotage were Louis’s way of punishing himself for the sins inherent in his condition, but he never gives any indication of seeking atonement. For all their superficial similarities, Louis is not Angel on “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” striving to pay off several lifetimes’ worth of spiritual wergild. Louis, to all appearances, is just one of those infuriating bores who are never happy unless they’re miserable.

The situation is not helped one bit by Brad Pitt’s performance, either. Pitt hated the role, which he apparently accepted without giving it half as much thought as he should have. Once it became obvious how empty the part really was, Pitt even went so far as to try backing out of the project. When he was told that reneging on his contract would cost him $40 million, Pitt did the next best thing to backing out— he checked out, going through the motions of the role without putting any meaningful effort into it. In other words, when you see Louis pouting, bitching, and whining his way through a scene like a sullen little ass-baby, that isn’t acting. It’s Brad Pitt being a sullen little ass-baby for real. We shouldn’t be too surprised, then, that Pitt displays not the slightest trace of chemistry with any of his fellow actors, despite the various outsized passions that ostensibly grip Louis throughout his unnaturally prolonged life. That would be bad no matter the circumstances, obviously, but it’s nearly fatal here, in a film that asks us to believe that one character after another— Lestat, Armand, Malloy— would become spontaneously fascinated by and attracted to such a barely animate sack of wet mice.

What do surprise are the respective contributions of Antonio Banderas, Tom Cruise, and Kirsten Dunst. Banderas is surprising in a bad way, for like Pitt, he is unutterably drab and forgettable. I don’t understand how that’s even possible for the star of Desperado— for Pedro Almodovar’s favorite personification of male kink!— yet he somehow manages to make the most powerful vampire on Earth seem wan, effete, and sexless. Fortunately, Cruise goes to the opposite extreme. I’ve never gotten on with Cruise as an actor. At best, he’s a blank screen onto which unsatisfied straight girls can project their most banal romantic fantasies, and at worst he’s the world’s smarmiest Gen-X douchebag. In Interview with the Vampire, though, Cruise gives the performance you might have expected from Banderas. His Lestat is a swaggering, virile, gleeful, puckish force of malevolent nature, the very antithesis of hangdog old Louis and Armand with his Fabio hair and his scrotum full of cobwebs. When Lestat gets sidelined at the end of the second act, Interview with the Vampire loses something that it never gets back until the final scene. He gets to deliver the line of the movie, too, although I’m not going to tell you what it is. Even so, it’s Kirsten Dunst who gets the MVP award. Twelve years old, and the kid steals the entire picture, despite having to compete with an experienced Hollywood star in the best performance of his career. Claudia is the scariest bent little girl since Alicia Witt’s precocious Bene Geserit superwitch in Dune, and wouldn’t be matched again until Daveigh Chase’s Samara in The Ring. She hits that perfect combination of sweet and soulless, cute and diabolical. And Dunst plays her with a maturity and depth of understanding that seem like they ought to be far beyond her reach at that age.

Finally, there’s one thing for which Interview with the Vampire unquestionably deserves special notice, if not necessarily special commendation. This is one of very few vampire movies I know of in which the principal conflict does not concern the turning or saving of some human character. Indeed, there are no human characters here of any consequence to the main story. Rather, the conflicts are all between or within the vampires themselves. Louis grapples fruitlessly with the moral implications of his condition, while Lestat plays the increasingly exasperated devil on his shoulder. Claudia’s affection for her adult companions curdles into hate and resentment in the face of her infinitely deferred puberty. Louis and Claudia fail to fit in with the crowd at the Theatre du Vampires, with ultimately deadly results. Very little of this stuff quite lands, but the mere fact that Interview with the Vampire isn’t about any of the things that vampire stories have been about since John Polidori wrote his supernatural hatchet job on Lord Byron in 1819 is a mark in its favor. Successfully or not, Interview with the Vampire tried something new.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact