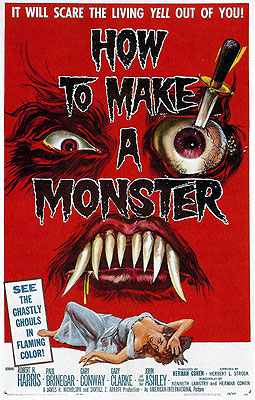

How to Make a Monster (1958) ***

How to Make a Monster (1958) ***

In 1957, the folks in charge at American International Pictures stumbled upon a formula that would revolutionize the production of B-horror films. They took a look at their audience demographics and concluded that horror movies with teenage heroes would be their golden ticket, and the genre has never been the same since. A whole slew of teenage monster flicks came off AIP’s production line in ‘57, including the famous I Was a Teenage Werewolf and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, Blood of Dracula (which more people would probably remember today if it had been called I Was a Teenage Vampire instead), and Invasion of the Saucer Men, in which teens battle midget aliens on lovers’ lane in between make-out sessions. But it was a year later, in 1958, that the studio released one of the best and certainly the smartest of the bunch, the all-but-forgotten How to Make a Monster. Not only is this picture a standout among the movies of AIP’s teenage monster cycle, it’s also one of the best inside jokes in cinema history.

How to Make a Monster is set on the lot of American International Studios, which has apparently dominated Hollywood horror for some 25 years. (American International Pictures, on the other hand, was barely three years old in 1958!) The studio has just changed hands, and its new chiefs, John Nixon (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’s Eddie Marr) and Jeffrey Clayton (Blood of Dracula’s Paul Maxwell), have in mind a radical new direction for the company. No longer will the name “American International Studios” be synonymous with horror; from now on, rock and roll musicals will be the name of the game! Nixon and Clayton apparently have some market research or other that predicts the impending demise of horror as a profitable genre, and it is this knowledge upon which they base their strategy for the company. Not everyone is happy with the plan, however, and foremost among the disgruntled is top AIS makeup man Pete Drummond (Robert H. Harris). He and his assistant, Rivero (Paul Brinegar, from Phantom of the Rue Morgue and Spaceship), have been with the studio from the very beginning, but with no new horror flicks under development, they’re going to be out of a job as soon as their current project (Teenage Frankenstein vs. the Teenage Werewolf— a movie I wish the real AIP had produced) is completed. At first, Drummond tries to prevail upon his new masters to reconsider their decision, but it is to no avail. Nixon and Clayton are hell-bent on making crappy knockoffs of Elvis movies. What’s a dedicated artist like Drummond to do in the face of such stubborn and willful myopia?

Well, for starters, he could add a mind-control drug to the formula for his monster makeup. That way, he’d be able to have the burly teen actors playing his Frankenstein monster and werewolf characters see to it that Nixon and Clayton meet with a little accident, as the saying goes. It wouldn’t be quite as good as having a pack of real monsters to do his bidding, but it’s better than nothing. Drummond starts with Larry Drake, the wolf boy (Gary Clarke, from Missile to the Moon and Dragstrip Riot), sending him to assassinate Nixon while he watches the rushes from that day’s shooting. No one notices the boy doing Drummond’s dirty work because Larry kills the studio head while a very noisy scene from the monster movie plays in the screening room, and when the cops come to investigate, everyone that Detective Thompson (Walter Reed, from Missile Monsters) interviews insists that Pete Drummond, the most likely suspect, has to be innocent. It looks like Drummond may well have committed the perfect crime here.

But there is one man who might be on to him. A studio security guard named Monahan (Dennis Cross, whom the ravages of time would later reduce to the sort of actor who appears in movies with names like Rape Squad) pays a visit to Drummond’s workshop on the day after the murder, and some of the things he says to Drummond strongly suggest that the watchman suspects something. Worried about what will happen when the police get around to interviewing Monahan, Drummond does the obvious thing, and sets about rubbing him out. He whips up another batch of his mind-control makeup, and orders Rivero to turn him into a sort of ape-man/Mr. Hyde thing. Then that night, under the influence of his own drug, Drummond tracks Monahan around the studio, corners him in an empty workshop far from the ears of the other guard, and strangles him to death.

The next day is the last day of shooting for Teenage Frankenstein vs. the Teenage Werewolf. With time thus growing short for him, Drummond gets ready to finish the job he began when he sent Larry Drake to kill Nixon. After Tony Mantell (Gary Conway, essentially reprising his I Was a Teenage Frankenstein role) finishes his scenes, Drummond keeps him in character until Jeffrey Clayton is ready to leave the studio for the night. Drummond then dispatches Tony to Clayton’s house, so that when the producer comes home, he finds the Teenage Frankenstein monster waiting for him. Tony kills Clayton, and then heads over to Drummond’s place so that the makeup artist can turn him back into a normal boy actor. On the way, though, Tony runs into (literally) a young black woman walking home from work. When she hears about the murder of Jeffrey Clayton, she goes to the police, and tells Captain Hancock (Morris Ankrum, from Kronos and Giant from the Unknown) that she encountered a “monster” on the street near Clayton’s house on the night that he was killed.

Obviously this means trouble for Drummond. His name had come up a number of times during the cops’ search for a man with a motive to kill John Nixon, and now that a witness has identified Clayton’s killer as a monster, AIS’s soon-to-be-unemployed makeup man becomes a better suspect than ever. And when the police medical examiner discovers traces of professional-grade makeup under Clayton’s fingernails, the finger of blame starts pointing at Drummond even more insistently. Detective Thompson rushes off to interview the makeup man again, but he arrives at the studio too late; with his movie finished and his contract terminated, Drummond has left the lot and cleaned out his workshop. But there is one thing Drummond left behind that may be of use to Thompson and his investigation— a jar of his special mind-control makeup carelessly discarded in his workshop’s trash can.

Meanwhile, Drummond and Rivero have brought Larry Drake and Tony Mantell over to Drummond’s place for a little wrap party. It is now that the two teenagers begin to suspect that Drummond has an unsavory secret. Given a chance both to see his extremely odd behavior at home and to compare notes on their experiences with him on the movie set, the two boys start to realize that something funny has been going on. To begin with, Larry and Tony find Drummond’s shrine to his monstrous creations— which occupies an entire room of his house— more than a little unnerving. And when Drummond and Rivero leave them alone for a while (locking them in the monster-head gallery, by the way), the boys get to talking and discover that they both have long gaps in their memories starting soon after Drummond put them into character on the last days of shooting. In addition, Drummond gave both of them similar speeches about there being enemies out to destroy them and their careers, but that Drummond could protect them if they would simply do as he instructed. When Drummond returns, and tells them he wants to add their visages to his gallery, the boys panic, understandably thinking Drummond means to put them back into makeup and decapitate them. The scuffle that then erupts in the candlelit gallery sets fire to the masks and draperies, and the boys are saved only by the timely arrival of Detective Thompson, who was just then on his way to question Drummond at home. The mad artist himself is burned to death in a futile effort to save his “children,” the wax and rubber monsters he had spent his whole working life creating.

How to Make a Monster owes its superiority to the prototypical I Was a Teenage Werewolf to a combination of speed and wit on the one hand, and the engaging, well-drawn character of Pete Drummond on the other. In marked contrast to most AIP movies of the time, How to Make a Monster zips right along, aided by the fact that its premise allows it to incorporate action scenes from Teenage Frankenstein vs. the Teenage Werewolf whenever the main plot starts to bog down. And the comedic elements are surprisingly funny for 1958, relying more on sly jabs at the foolishness and absurdity of the movie business than on the juvenile slapstick more typical of late-50’s B-movies. The scene in which Drummond watches the shooting of a song-and-dance number from one of Clayton’s new projects is especially amusing, and keep your ears open for moments when one character or another name-drops AIP productions then in the works (Horrors of the Black Museum, for example).

As for Drummond, he is one of the most complex and satisfyingly portrayed villains in the whole AIP horror/sci-fi canon. His frustration at the obvious stupidity of his new bosses’ plans for the studio, and his sense of betrayal over of the cavalier manner in which Nixon and Clayton propose to bring his career to a premature end make Drummond a very sympathetic personality, while his eccentric dedication to a job most of his shallow-minded peers find morbid and even faintly immoral makes him seem charming and likeable to anyone likely to be watching this movie today. And yet Drummond is a homicidal maniac whose grip on reality is tenuous at best, and he is beyond question the villain of the piece. But there is still another layer to Pete Drummond. Note that, on the one occasion when he feels compelled to commit murder directly, delivering the killing blow with his own hands, he has Rivero put him under the same “spell” that turns the teenage actors into Drummond’s killing machines. Does Drummond not trust himself to do the deed under his own power? Does he fear that he is still too civilized to kill a man without a mind-control drug to disable his conscience?

And then there’s the gimmick. Apparently most TV prints and at least some VHS editions of How to Make a Monster lacked this, but the final ten minutes or so were originally shown in color. The color sequence begins when Drummond lights the first of the candles that illuminate his private gallery of horrors, and runs to the very end of the movie. What makes this so cool (beyond its obvious kitsch value) is that it offers an opportunity to see what several earlier AIP movie monsters really looked like. Notable among the creatures mounted on Drummond’s walls are the heads of the She-Creature and a Saucer Man, and the face of the ridiculous alien from It Conquered the World. Seeing the latter in color is the biggest revelation— who would ever have guessed that the monster’s skin was colored in a bruise-like array of purples, reds, and blues?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact