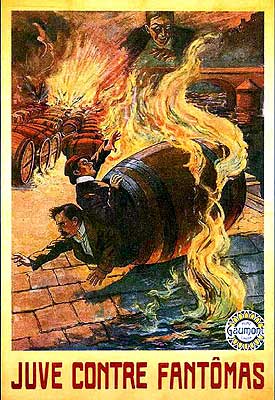

Juve Against Fantomas / Fantomas II: Juve vs. Fantomas / Fantomas: Juve Contre Fantomas (1913) **

Juve Against Fantomas / Fantomas II: Juve vs. Fantomas / Fantomas: Juve Contre Fantomas (1913) **

Louis Feuillade’s Fantomas is frequently described as a serial, and that isn’t technically inaccurate. The five constituent movies do collectively tell a more or less coherent story in which not only the core characters, but even many of the supporting figures recur in ways that won’t make a lot of sense if you watch the series out of order. Each successive chapter begins at least roughly where the last one left off, and the first two end with a clear setup for the next. But other typical features of the mature chapterplays are conspicuous by their absence. Most noticeably, the individual Fantomas installments are all much longer than those of a conventional serial, and there are nowhere near as many of them. Instead of twelve or fifteen episodes of 20-30 minutes’ duration, we have what amounts to five feature films (with the caveat that the concept of feature length was itself still being pinned down in 1913-1914). Three of the Fantomas installments run about an hour apiece. Juve Against Fantomas, the second film in the series, is a bit shorter than that, while the third, The Murderous Corpse, runs a fully modern hour and a half. Not coincidentally, the odd chapters out feel the most like a serial episode and a self-contained feature respectively, while the others wander a strange limbo between the two states. It follows that Juve Against Fantomas is the least satisfactory of the series when taken solely on its own merits. Like any chapter dug out from the middle of a serial for viewing without reference to its intended context, it seems too busy, too elliptical, and it both begins and ends with self-defeating abruptness.

Fantomas (Rene Navarre again) is still at large an unspecified length of time after cheating the guillotine, and Inspector Juve (still Edmond Breon) remains on his trail with the help of newspaper reporter Jerome Fandor (still Georges Melchior). In fact, Fandor will be a much bigger presence this time than he was in the preceding chapter. I’m not sure how that’s legal, but maybe they just did things differently in France 100 years ago. The pair’s current investigation concerns a female corpse crushed beyond recognition, which a certain Dr. Chaleck claims to have found in his house upon returning from several days out of town on business. Discovered on the victim’s person were identity papers belonging to Lady Beltham, a known associate of Fantomas, but the condition of the body is such that there’s no telling whether or not it’s really her. Dr. Chaleck is unable to explain how the lover of a criminal mastermind might have gotten herself squished to death in his home while he was away— nor, I’m afraid, will Feuillade be much help in that department even after all the other details of the story come out. Still, Juve reports to his superiors that he can find no basis on which to connect Chaleck with the murder, or with Fantomas either. He surely plans to keep looking, though.

Actually, the connection between Chaleck and Fantomas is trivially easy to sort out: they’re the same person. Juve beings to suspect as much when his surveillance of the doctor catches him sneaking into a rough, proletarian neighborhood, disguised as a rough proletarian. The doubly incognito criminal (who goes by “Loupart” in this identity) meets up with a young woman named Josephine (Yvette Andreyor, from The Hunchback and The Castle of Fear), who slips him a letter reporting her progress on their latest heist. Josephine has secured the courtship of Mr. Martiale (Laurent Morleas, of The Man Without at Face, who would return to the series later on as a different character), an agent of Bercy wine magnates Kessler & Barru, and she has learned that he’ll be arriving in Paris soon with 150,000 francs for some manner of sales or distribution transaction. While he’s in town, Martiale intends to take Josephine on an excursion by train. She’ll keep Loupart posted on further developments as they arise. Juve’s pursuit of Chaleck is quickly thwarted by a member of the Loupart gang, but Fandor fares better in keeping up with Josephine. In fact, he does such a good job that he’s actually on the train with her and Martiale when the girl springs her trap, and a mob of masked goons descend upon their car. Fandor and the wine salesman only narrowly escape death when the robbers detach their victims’ coach from the rest of the train, sending it coasting helplessly downhill, straight into the oncoming Simplon Express! Kessler & Barru have outsmarted the criminals, however. All 150 of the thousand-franc banknotes that Martiale was carrying had been cut in half, the other halves to be sent along in 30 days upon completion of whatever contract the agent had been negotiating. Whoops.

Obviously Fantomas wants the rest of that money. With that in mind, he dispatches the Loupart gang to the Kessler & Barru plant in Bercy, but he also arranges for Juve to meet them there. Fantomas sends Juve a telegram signed “Fandor,” inviting him to help stake out the wine merchants’ facility, and when the inspector arrives in response, he walks straight into an ambush. Lucky for him, Fandor really was staking out those docks and warehouses at the time, so the odds in the resulting battle end up being at least slightly less unfavorable.

After their narrow escape from that trap, the investigators get back onto Josephine’s trail. They find her at a Montmartre nightclub called the Crocodile, where she has just finished drinking a lightweight dandy under the table. Under threat of arrest, the girl leads Juve to Fantomas, who happens to be sitting at a table in the next room in the respectable guise of Dr. Chaleck. Convenient, eh? Now it’s Fantomas’s turn to cheat capture, thanks to a breakaway overcoat tricked out with a pair of puppet arms.

Next, we learn the rather startling fact that Lady Beltham (still played by Renee Carl) not only isn’t dead after all, but has apparently been in police custody all this time. Released at last due to lack of evidence linking her to either the murder of her husband or to the escape of Fantomas from Sante Prison’s death row (wait— really?!), she has taken refuge in a nunnery outside Paris, even going so far as to put her villa in Neuilly up for sale. Lady Beltham can’t hide from Fantomas, though. Writing to her at the convent, he extorts from her a renewal of their relationship, to be carried on each Wednesday at midnight at the Neuilly house. Their activities inevitably convince the superstitious caretaker that the place is haunted, but Juve and Fandor quickly settle on an alternate interpretation of the strange sights and sounds reported from the villa once each week at the witching hour. They go to the Beltham house the following Wednesday night, and soon find themselves in a position to eavesdrop on the villain as he plots once more to kill Juve. This time, it’s going to involve a “silent executioner.” Can’t wait to see that, can you? Believe it or not, it’s a huge python which Fantomas releases into the detective’s flat through the bedroom window, and incredibly enough, Juve defeats it by wearing a nail-studded corset and bracers to bed! (Shades of the Lambton Worm…) With the ophidian menace bested, the stage is set for a showdown at the villa. But just like last time, don’t go expecting too final a finale. In fact, Juve Against Fantomas ends on a full-fledged cliffhanger.

Much as I enjoyed it, the bit with the python really does epitomize everything that’s wrong with Juve Against Fantomas. It’s an outrageously implausible turn of events that seems to come out of nowhere, and it’s resolved in a manner even more absurd than its setup. To be fair, I realize in retrospect that the weird business about the pulped female corpse at Dr. Chaleck’s house was supposed to be foreshadowing, but the attempt to cock Chekhov’s gun fails because that’s not how pythons work. Constricting snakes don’t crush their prey— they asphyxiate it— and they don’t normally kill things they’re not interested in eating. Neither does the squished dead lady foreshadow Juve’s deduction that the “silent executioner” Fantomas will be dispatching to kill him must be a colossal snake. What we really need for that is an intertitle establishing that Juve has made the connection between Fantomas’s odd statement about how he means to kill the inspector and the woman whose crushed body so baffled him at the start of the film. To go straight from “silent executioner” to Juve going to bed in a corset of nails is cheating, pure and simple. Even the final outcome of the python incident reeks of bullshit, since the snake survives its spiky surprise to be smoked to death later on in its lair within the heating ducts of the Beltham mansion.

The whole movie is like that to one extent or another, inattentive to detail and too ready to cut indispensable narrative corners. We never do learn who the crushed woman was, for example, and the cops’ early assumption that she may be Lady Beltham is rendered nonsensical later, when we hear that the latter woman had been locked up since the end of the last movie while the police tried to figure out whether they could make a conspiracy charge stick to her. What, did nobody think to tell Juve that they had Fantomas’s mistress in custody? Less destructive, but still annoying in its way, is the lack of meaningful connection between the “haunting” of Beltham house and the Kessler & Barru caper. It’s here that Juve Against Fantomas feels most like part of a conventional serial, and if the two segments really had been released separately, the dissociation probably wouldn’t have been a problem. But with the one vignette following directly on the heels of the other, while the second neglects even to mention the first, it comes across as inexcusably careless writing. Such sloppiness is irritating not only in and of itself, but also because it deprives Juve Against Fantomas of one of In the Shadow of the Guillotine’s best features. There’s no longer that shrewdly balanced tension between veracity and pulp convention throwing our sense of reality out of whack. What we get instead is pulp in its crudest and most unselfconscious form, and Feuillade’s visual artistry, although no less impressive than it was the first time around, can’t make up here for a story that is simply not believable on any level.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact