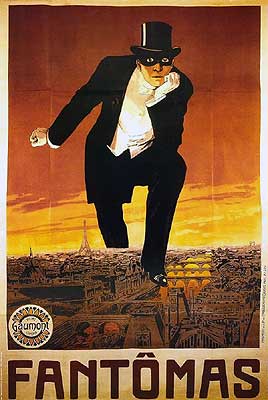

Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine / Fantomas / Fantomas: A l’Ombre de la Guillotine (1913) ***

Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine / Fantomas / Fantomas: A l’Ombre de la Guillotine (1913) ***

Okay— now I think it’s time to give my crackpot theory about the earliest prehistory of horror cinema a full airing. It seems to me that if you go all the way back to the first two decades of the last century, when “horror cinema” was barely the faintest inkling of a concept, it is possible to discern certain specific national contributions to the latent genre. The Germans, most famously, were the first to make a habit of dealing unabashedly in the supernatural, populating films like The Student of Prague and Monster of Fate with genuine wizards, devils, and doppelgangers while their counterparts abroad generally preferred to explain such things away in the final scene. The Brits, as I’ve said elsewhere, displayed a fascination with true crime, mining the gory details of infamous real-life murder cases for subject matter. Squeamish and puritanical Americans hid at first behind the alibi of adapting classic literature, then enthusiastically contracted the same mania for spooky houses that already gripped the popular stage. But the French case is remarkable, because what they brought to the table impacted not just horror, but virtually all of genre film and fiction, and it began making its influence felt even before the rise of cinema as a medium of mass entertainment. What the French contributed was a character type, the obsessed, trauma-driven outcast seeking to remake the world (or at least his world) to his liking, regardless of what society has to say about it.

A moment’s reflection will expose the vast breadth of this character type’s importance. He’s every slasher and masked arch-criminal and mad scientist, plus most of the Satanic cult leaders and supervillains. He figures in horror, sci-fi, Westerns, detective stories, historical adventures, and melodramas, to say nothing of the superhero genre, which basically couldn’t exist without him. Although he’s usually a villain or an antihero, he does occasionally turn up in a straight hero’s guise as well— but only an exceptionally talented writer or filmmaker can usually manage the latter interpretation without sacrificing something central to the trope. And while such characters certainly were not unknown outside of France, a quick roll-call of crucial early examples demonstrates that French authors did more to define them than anybody else: Jules Verne’s Robur and Captain Nemo, Victor Hugo’s Gwynplaine and Quasimodo, Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera and Cheri-Bibi. As for the movies specifically, one Frenchman in particular was in the forefront— Louis Feuillade, who spent the 20th century’s teen years cranking out an impressive volume of work detailing the extralegal adventures of Fantomas, Judex, and an anarchistic gang called the Vampires.

Mind you, that wasn’t all Feuillade did. Indeed, the sheer scope of his output makes my head spin. During his two decades as a contract director-scenarist for the French arm of the cross-Channel Gaumont firm, Feuillade signed his name to over 600 motion pictures. The great majority of those were shorts, of course, but as the film industry grew beyond single-scene vignettes and one-reelers, so did he. Feuillade was in on the birth of the feature film as we know it, and he was a pioneer of serials as well. He had a hand in expanding the art form’s initially limited visual vocabulary, standing among the first to appreciate how much the camera could do even in a film with little or no special effects trickery. He was one of the true titans of early cinema, and one of the few whose mature movies anticipate the future more strongly than they invoke the past. But the main thing that matters for our present purposes is that he was the mastermind behind the weirdest and wickedest crime pictures of his age, in which the villains frequently remind one more of the Abominable Dr. Phibes than of Professor Moriarty.

A Russian noblewoman named Princess Sonia Danidoff (Jane Faber) takes a suite at the Royal Palace Hotel in Paris. Evidently she’s expected, as the desk clerk has waiting for her an envelope containing an astonishing sum of 120,000 francs. Up in her rooms, the princess stashes both the money and her pearl necklace in a compartment of the escritoire before heading into the bedroom with her maid to change out of her flashy going-out-in-public clothes. While she is thus occupied, a distinctly Rasputinesque gentleman in a black tuxedo (Rene Navarre, from The Haunted Room and the 1938 version of Cheri-Bibi) lets himself in from what I take to be a balcony outside. He doesn’t quite have time to pocket the valuables and make his escape, though, before the princess returns. Naturally she’s rather put out at what she finds going on in her sitting room, but the thief is convincingly menacing enough to keep her quiet so long as he’s within reach of her. Before popping out through the door into the hotel corridor, he gives Sonia a perplexing blank calling card, which holds her attention long enough for him to take up a position by the elevator to the lobby. When the princess calls the front desk, and the head bellhop takes the elevator up to her floor, the thief is thus well-placed to throat-punch the unfortunate man on his way to the rescue. Then the robber helps himself to the bellhop’s uniform, discards his false beard and moustache, and escapes out the very front door on a bogus errand to the police. By that point, the invisible ink on his calling card has faded into legibility, revealing a single word: Fantomas.

That name is well known to both Inspector Juve of the Security Service (Edmond Breon, of The Vampires and Gaslight) and Jerome Fandor, reporter for La Capitale (Georges Melchior, from Queen of Atlantis). The two men already suspect him of being somehow behind the disappearance of English businessman Lord Beltham, and Juve is soon put in charge of that case as well as the theft at the Royal Palace Hotel. Sensibly enough, he means to start by interviewing Lady Beltham (Renee Carl, whom Feuillade would also hire back for The Vampires), the missing man’s wife. When the inspector arrives at the Beltham mansion, Lady Beltam is entertaining an old associate of her husband’s, by the name of Mr. Gurn. It’s hard to be really certain at the moment, because of his drastically different hair and facial foliage, but this guy Gurn sure does look like Fantomas. And indeed he becomes very agitated when the butler enters bearing Juve’s card. Gurn insists that Lady Beltham hide him at once, but in his hurry, he leaves his hat in the drawing room. Juve, who after all makes his living from noticing things, spots the hat immediately, and also observes the tag marked “G” on the inside band. Consulting Lord Beltham’s address book with the lady’s permission, the inspector discovers an entry for Mr. Gurn of 147 Rue Lavert, and although his hostess claims not to know any such man, it isn’t as though there’s another “G” name in the directory. Gurn, rightly suspecting he’s been found out, places an order the moment Juve leaves for the urgent pickup of three trunks currently sitting in the foyer of 147 Rue Lavert, which are then to be shipped out to his other address in Johannesburg (an address apparently unknown to Lord Beltham, and thus unknown to the inspector as well). Juve is just a tad faster than the shipping company, however, and when he and a uniformed cop open up Gurn’s trunks, one of them proves to contain Lord Beltham’s corpse.

Gurn understandably lies low after that, hiding out for two weeks in, of all places, his victim’s own house. His choice of spider holes looks a little less brazen, though, once we learn that he and the widow Beltham are lovers. Still, Juve is a formidable adversary, and he susses out exactly where Fantomas is hiding in time to trap him when at last he feels safe to show his face again in public. Juve and his men arrest Gurn right outside the Beltham estate’s garden gate.

In an unexpected touch of realism, it takes six months for Gurn’s trial and sentencing hearing to run their courses, by which time press and public have glutted themselves on the lurid details of the case. Equally noteworthy, it isn’t Fantomas himself who figures out how to circumvent his date with the guillotine, but Lady Beltham. Between her husband’s money and the arch-criminal’s, she is now an extremely wealthy woman— more than wealthy enough to bribe one of the guards at Sante Prison (an actor credited only as Naudier) to arrange one last conjugal visit for her on the eve of Gurn’s scheduled execution. (In my favorite moment of the whole film, the scheming lady secures the guard’s silence and continued cooperation by making him sign a receipt for the bribe money!) Meanwhile, at the Theatre du Grand Treteau, the star of a blood-and-thunder melodrama called The Stain of Blood (The Werewolf’s Andre Volbert) is creating a popular sensation by playing the villain’s role done up as the spitting image of the infamous Gurn. On the evening before head-chopping day, Lady Beltham sends the actor a note begging him to meet her at a certain address— in costume, mind you— so that she can fulfill a fantasy she’s been nursing ever since opening night. One assumes this is not the weirdest proposal Valgrand has ever received from a fan, because he goes for it no questions asked. Naturally, the address appointed for their tryst is the same one to which the crooked guard was supposed to deliver the real Gurn, and a quick switcheroo results in the cops taking a drugged Valgrand back to the prison with them at the appointed hour instead of Fantomas. It’s the perfect escape, no? Well, maybe if Juve weren’t there in the morning to witness the execution of his nemesis. Will the inspector spot the wig and false moustache on the condemned man in time to save an innocent ham? Will he be able to follow the trail of corruption back to Gurn wherever he is now? Feuillade made four more of these things over the next year and a half— does that sound like this could be the end of Fantomas to you?

Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine surprised me with how thoroughly nasty its version of the title character is. I went into this film with preconceptions formed by 60’s European arch-criminal movies like Danger! Diabolik and Psychopath, in which the super-thief is usually portrayed as an admirable rebel against corrupt authority. I probably should have figured that such characterizations were a product of their era, and that the lines between good and evil would be drawn in a more straightforward way in a picture made before the First World War. On the other hand, there was plenty of moral ambiguity in Fantomas’s literary antecedents from the century before. Maybe the tumult of the first half of the 19th century (at least equal to the tumult of the mid-20th) left French culture in a 60’s-like mood of skepticism toward traditional values too. Regardelss, Feuillade wastes very little time in placing Fantomas beyond the pale of the “gentleman thief” archetype. Even the opening caper against Princess Danidoff, which starts out in that mode, takes on a disquieting edge from the brutality with which Fantomas manhandles the bellhop. The arch-criminal looks positively sordid by the middle of the second act, when we see that he conspired with his mistress to murder her husband. And with a climax that hinges upon a plot to send an innocent man to the guillotine in the villain’s place, there’s no room left for interpreting Fantomas or Lady Beltham, either, as anything less than complete monsters.

That harshness of characterization in the villains intersects in a fascinating way with the shameless incredibility of Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine’s plot. By rejecting the romance of the gentleman thief to portray Fantomas as starkly ruthless and untroubled by conscience, Feuillade tempts us to see the villain as “realistically” depicted. At the same time, though, Feuillade wholeheartedly embraces the darker romance of the diabolical genius, so that the things Fantomas does apart from the murder of Lord Beltham become almost purely fanciful. The tension between convincing characterization and borderline-fantastical action gives rise to a sense of overlapping, contradictory realities, approaching at times the outskirts of the surreal. That quality is lost somewhat in the sequels, as Fantomas grows more extravagantly wicked and his schemes increasingly bizarre. Here at the beginning, though, it’s pleasantly disorienting to see so believably venal and brutish a character as the perpetrator of such baroque wrongdoing.

Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine also puts Feuillade’s precocious mastery of cinematic technique on full display. Modern viewers will of course notice plenty of ways in which this movie is extremely old fashioned, like the static camera, the opening credits mimicking a theatrical curtain call, or the sets that just barely attempt to hide their artificiality. And yet there’s also an almost subliminal modernity to Feuillade’s direction, something the conscious mind doesn’t easily notice without prompting, but that makes its presence strongly felt just the same. It’s all in the blocking of the action onscreen. The reason Fantomas never seems stagy even despite its rigid camera setups and its eschewal of closeups on anything save letters, business cards, and the like is because Feuillade composes and choreographs its scenes to be radically dependent on the placement of the camera. People in this movie are almost constantly in motion, even if they’re just rolling a cigarette or futzing about with some other small prop, and they’re as liable to enter the frame through a door visible in the background as they are to come in from the wings. All that activity would be pandemonium on a theater stage, with the actors all obstructing each other’s sight lines and most of the audience unable to see any of the carefully contrived prop business. But Feuillade understands that he’s not directing for the stage. The only vantage point he need worry about is the camera’s, so he can afford to keep the actors swishing and swooping around the set like globes in an orrery. The effect is strikingly similar to that of the complicated long takes favored by many artier filmmakers of later eras. Feuillade also displays subtler but no less significant gifts as an adaptor. Although I gather that Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine’s overall structure was carried over from the source novel by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, it was extremely perceptive of Feuillade to retain it. It isn’t often that one sees a film like this in which the seemingly all-powerful villain is defeated fair and square in act two, leaving the endgame to revolve around his accomplices’ efforts to spring him from death row. Throw in performances that are toned down a notch or two from the histrionics typical of the early 1910’s, and you can see how Feuillade earned his reputation as a driver of advances in the state of his chosen art.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact