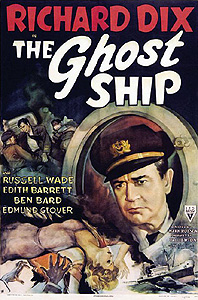

The Ghost Ship (1943) ***

The Ghost Ship (1943) ***

Hang on there, buddy— take another look at that release date. The movie I’m talking about here isn’t the new Dark Castle flick with the ad art stolen from Death Ship, but rather the rarest of the nine horror movies producer Val Lewton made for RKO between 1942 and 1946. The Ghost Ship had been out of legitimate circulation (I’ve heard that a few bootleg prints exist) for most of 60 years as the result of an ugly legal wrangle which has only recently been cleared up. Evidently a pair of screenwriters sent the studio an unsolicited script about a sea captain who goes mad and a young subordinate officer who becomes the object of his homicidal attentions, which was returned to them unbought and, from the initial look of things, unread. But then, in the fall of 1943, word of this movie’s production appeared in the Hollywood trade magazines, and those two writers (I haven’t been able to track down their names) had a look at the story and said, “Holy shit! That’s our movie!” They sued the studio for plagiarism and won; the court awarded the writers some $25,000, while The Ghost Ship was withdrawn from release after only a couple of weeks, never to be seen again. Or such, at any rate, was the intention. I don’t really know what has changed to allow this movie to escape from its tomb, but I’d be willing to bet that the deaths of all the people originally involved (to say nothing of the demise of the RKO studio) had something to do with it. Regardless, it’s a damned good thing that change took place, because The Ghost Ship is too good a movie to be gathering dust in a vault somewhere.

Thomas Merriam (The Body Snatcher’s Russell Wade) is a young merchant mariner just off the training ship, who has signed on as the third officer aboard the freighter Altair. Merriam was selected personally by Captain William Stone (Richard Dix, from Seven Keys to Baldpate and Transatlantic Tunnel) himself to replace an officer who died under somewhat mysterious circumstances on the homeward leg of the ship’s last voyage. This is only the first indication Merriam sees that the blind beggar he encountered as he mounted the gangway, who warned him that the Altair was “a bad ship,” may have had the right idea. In fact, the first casualty of the vessel’s latest voyage drops before the ship even sets sail. While the captain oversees the roll call of the new crew, it is discovered that an elderly seaman named Jenson died of a stroke or a heart attack on his way to the quarterdeck.

As the trip to South America wears on, however, Merriam will increasingly come to suspect that it isn’t the Altair that’s bad, but rather her master. Captain Stone displays a reckless disregard for the safety of his crew when he refuses to allow Merriam to order the tying down of one of the ship’s big cargo hooks, despite indications that the Altair is headed for stormy weather. The hook has just been painted, you see, and Captain Stone doesn’t want the finish marred by the tethering lines— he “like[s] a neat ship.” Well just as Merriam warned, that hook (which must weigh close to 500 pounds even without factoring in the heft of the chain to which it is attached) begins swinging wildly as the wind and the waves pick up, and the crew has a hell of a time securing it. And for that matter (though no one raises the issue), it scarcely seems to me that Stone’s professed desire to keep a neat ship can have been furthered by allowing the free-swinging hook to clatter repeatedly against the Altair’s upperworks and to destroy one of the ship’s boats! The captain’s justification for his handling of the situation when he is later questioned by his third officer is exceedingly lame, although Merriam buys it at the time. Stone tells Merriam that his responsibility for the lives and safety of his crew gives him certain rights to risk that safety. That may be true, as far as it goes, but could any truly responsible man honestly claim that it goes far enough to excuse jeopardizing life and limb for the sake of a nice, glossy cargo hook?!

The hook incident is only the beginning. A deckhand named Peter (Paul Marion, from The Mysterious Dr. Satan and the 1943 version of The Phantom of the Opera) comes down with appendicitis, and Stone (to whom falls the task of performing the surgery under radio direction from a doctor on the mainland) freezes up with the scalpel in his hand. Merriam has to step in to finish the operation, but in order to avoid embarrassing the captain, Merriam swears radioman Jacob “Sparks” Winslow (Edmund Glover, from The Curse of the Cat People and A Game of Death) to secrecy regarding who actually did the cutting. Now with one man dead and another laid up in sickbay, the crew finds itself struggling to keep abreast of all the work that needs to be done. One sailor, Louie Parker (Lawrence Tierney, of Exorcism at Midnight and The Horror Show), goes to the captain citing recently passed international shipping regulations that supposedly require the master of a seriously undermanned vessel to put into port to hire replacement crewmen. Stone turns Louie away, saying that he and he alone is the law aboard the Altair. He then makes the odd statement to Parker that “Some captains would hold this against you, you know.”

What do you want to bet that Stone is one of those captains? The next day, Parker is part of a team assigned to clean the corrosion off of the anchor chain, the hawse pipes, and the compartment in which the chain is stored while the anchor is shipboard. Parker himself is down below decks, guiding the chain to make sure that it coils up properly, when the captain walks by. It isn’t initially clear whether he does so deliberately, or whether he simply didn’t notice that there was a man in the compartment, but he closes the hatch to the chain locker as he passes, locking Parker inside with several thousand fathoms of heavy-gauge steel chain. There isn’t a whole lot left of Parker when Merriam finds him a bit later. Now Merriam was present when the dead seaman came to Captain Stone about the supposed requirement for putting into port, and he heard the captain’s enigmatic words regarding what “some captains” would do in his position. With a dead man in the chain locker who could have been trapped down there only if somebody— somebody who likes a neat ship, perhaps— had closed the hatch on him, those words start to sound an awful lot like a threat. Merriam makes the connection, and goes to First Officer Bowns (Ben Bard, from The Leopard Man and The Seventh Victim) in an effort to get Stone declared unfit to command. Bowns isn’t interested, but when the Altair arrives at its destination, the young officer speaks up again, this time making his case to an agent of the shipping company that owns Stone’s vessel. Agent Roberts (Boyd Davis, of Terror by Night and The Strange Case of Dr. Rx), an old friend of the captain’s, calls an informal hearing rather than beginning an official inquiry, and Merriam is first astonished, then discouraged, and finally horrified to discover that not a single one of his shipmates is prepared to come forward in support of his assertions, not even those who were assigned to the same work detail as Louie Parker. Realizing that his career as the Altair’s third officer is at an end, Merriam packs his bags, and begins making other arrangements to get back to the States.

Merriam must have done something to piss off Lady Luck, however. After an unexpected meeting with a woman named Ellen (I Walked With a Zombie’s Edith Barrett) who has been conducting an odd, intermittent affair with Captain Stone for many years, Merriam goes out drinking. Outside of one of the bars downtown, he sees a former shipmate of his, Billy Radd (calypso singer Sir Lancelot, whom Val Lewton used to cast in his movies at the slightest provocation), being threatened by a gang of sailors from a German ship (one assumes these fine specimens of the Aryan race take exception to the idea of an untermensch visiting the same watering hole as them). Rushing to Billy’s defense merely makes him the focus of the Germans’ violence instead, and Merriam is beaten into unconsciousness. South American port cities not being known for their state-of-the-art medical facilities, Billy figures Merriam’s best bet is the Altair’s sickbay, and thus the former third officer finds himself back aboard Captain Stone’s ship despite his intentions. A few days later, when the captain tells his former subordinate that there are no hard feelings, it’s easy to see why Merriam isn’t reassured. “You know, Merriam,” says Stone, “some captains would hold all this against you.” Bon voyage, Tommy…

Like all of the Val Lewton thrillers, The Ghost Ship works mostly by implication for much of its length. Captain Stone’s madness is kept well in hand until the final act, and the difficult balance upon which the story hinges— the captain’s behavior must be sufficiently worrisome that the audience agrees with Merriam’s assessment of the man’s personality, but have enough alibis built into it that the refusal of the authorities to take any action against him is believable— is struck successfully. Matters are further improved by the filmmakers’ decision to make Stone a complex character with realistic motivations, rather than merely a stereotyped homicidal maniac. He rightly believes that the Altair is for all practical purposes a world unto itself while it’s out at sea, and that responsibility for the smooth functioning of everything in that world ultimately rests on his shoulders. The obsessive fixation he displays on the notion of authority is thus understandable, and to some extent even justified. Where Stone goes wrong, however, is in failing to appreciate that authority and power are not the same thing. The difference lies in legitimacy— the authoritative man earns the moral right to his power by wielding it only in a fair, judicious, and responsible manner. Used capriciously, power sinks inevitably toward the level of naked force. The remarkable thing about Captain Stone is that he seems to have internalized some form of this idea even though he clearly does not grasp it consciously. Although he would never admit it to his men, Stone knows that his behavior is in some important sense out of line, and he fears that his inability to control himself without undermining the commanding demeanor he believes is essential to his role means that he is going slowly insane. His big scene with Ellen, in which he expresses his worries about the state of his own mind, is a masterful touch, in that it simultaneously raises the first unambiguous sign that Merriam isn’t just imagining things and leads you to think there might be some kind of hope for the captain after all.

But what raises The Ghost Ship up in the direction of Cat People and The Seventh Victim and away from such RKO rabble as I Walked with a Zombie, The Leopard Man, and Isle of the Dead is a screenplay that knows when to stop hinting and get down to business. Ambiguity is fine, but it’s a rare horror movie that can get by solely on the strength of what might be happening out of the camera’s sight. And in the case of a movie like The Ghost Ship, where the only evil is of a strictly human variety, playing it too mysterious would definitely be a bad idea. The climax of this film does not screw around, though, and is really quite shocking in the context of its era. Not only that, it finally redeems what had up until then been an utterly useless and profoundly annoying character, the scar-faced mute (Skelton Knaggs, from Bedlam and House of Dracula) who periodically pops up to deliver ridiculous voice-over commentary. This character alone probably cost the movie half a star in my reckoning, so it was a relief to see him do something at last beyond serving as the world’s worst Greek chorus. It probably wouldn’t be considered exactly a classic even if it hadn’t vanished off the face of the Earth for close to six decades, but the reappearance of The Ghost Ship is still something worth getting excited about for fans of old horror movies.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact