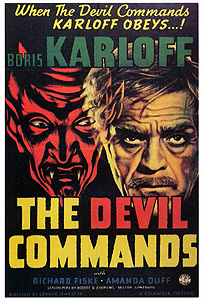

The Devil Commands/When the Devil Commands (1941) -**½

The Devil Commands/When the Devil Commands (1941) -**½

It is an oft-made and basically legitimate criticism of Columbia Pictures’ early-40’s mad doctor movies that they mostly keep covering the same ground over again. However, the last seriously intended entry in the series— 1941’s The Devil Commands— diverges in several significant ways from the template established by The Man They Could Not Hang. Yes, it’s still Boris Karloff coming to grief over a program of medical research extrapolated with unusual credibility from what was then up-to-the-minute real-world science. But it’s also an adaptation of William Sloane’s novel, The Edge of Running Water, rather than yet another original story by Karl Brown and/or Robert Andrews. It mixes science fiction with the supernatural in a way that not only wouldn’t even begin to catch on for a good quarter of a century, but was almost without precedent in American motion pictures. Most peculiarly, it seems to take a lot of its structural cues from Rebecca, of all movies, although that isn’t exactly a point in its favor. Along with being nominally presented from the future perspective of its nominal heroine, it both opens and closes on a lingering shot of the detailed miniature set representing the house where the key parts of the action take place. The Devil Commands even sets most of its major transitions to the tune of said heroine’s hilariously clunky voiceover narration, emulating what was easily Rebecca’s silliest feature. And as that might be taken to imply, this most individualistic of the Columbia mad doctor flicks is also far and away the most prone to overreaching itself with ludicrous results.

Oh— and at no point does the Devil actually command anything. Instead, what we have here is an admirably creative reinterpretation of a subgenre at least as gray-bearded as the spooky house mysteries and surgical misadventures that were riffed on by The Man They Could Not Hang and Before I Hang respectively, for The Devil Commands is really a séance movie at heart. It will take a while for that to become apparent, though. When we are introduced to Dr. Julian Blair (Karloff), it is in the context of his recent discovery that the human brain gives off measurable electromagnetic impulses, and that those impulses take the form of a wave when their intensity is graphed against time. Blair is demonstrating this for several of his colleagues with the help of his assistant, Dr. Richard Sayles (Richard Fiske), gushing as he does so about the potential applications of his findings. He’s just getting around to the point about each individual’s brainwave pattern being as distinctive as a set of fingerprints when his wife, Helen (Shirley Warde), arrives at the lab to remind him that they’re supposed to be picking up their daughter, Anne (Amanda Duff), from the train station. It’s the girl’s twentieth birthday, and she’s coming home for a few days to celebrate with her parents. Even so, Blair manages to sweet-talk Helen into postponing the trip just a few minutes longer, so as to show off the uniqueness of individual brainwave patterns by recording hers and comparing her chart with that of Dr. Sayles. Then it’s a quick detour to the bakery from which Helen commissioned Anne’s birthday cake.

That’s where things go catastrophically wrong for the Blairs. It’s pouring down rain when Helen and Julian arrive at the bakery, and there’s nowhere to park on the street out front. Helen stops the car to let Julian off, saying she’ll just circle the block until he comes out, but instead she gets into a terrible crash when either she or another driver loses control on the sopping-wet pavement; she lives just long enough for Julian to reach the wreck of their Ford and pull her from it. Dr. Blair simply shuts down in the aftermath of the tragedy. He avoids both Sayles and his daughter, spends as little time as he can manage in the house, and coops himself up in the lab, not really doing much of anything for hours at a time. One night, while engaged in the latter pursuit, Blair absentmindedly switches on the power to his brainwave-recording equipment, only to turn it off again during one of his more lucid moments. Then Blair finds his attention drawn to the graph, which ought to bear nothing but a flat trace for the minute or two that the machine was turned on, given that the receiver wasn’t hooked up to anyone or anything. That’s not what Julian sees, though. Not only is there a wave pattern on the graph, but it’s Helen’s wave pattern! Blair’s research has already shown that only Helen’s brain could produce that pattern, so it’s difficult to find any explanation for the graph save that the idle recorder was somehow picking up Helen’s thoughts from beyond the grave.

There are some claims that people just aren’t ever going to buy, though, and I’d put “Hey, everybody! I made a transdimensional recording of my dead wife’s brainwaves last night!” way up near the top of my personal list of them. None of the scientists for whom Blair demonstrated his encephalograph earlier will believe him, and more painfully, neither will Sayles or even Anne. And really, considering that Julian has been acting none too sane about Helen’s death, it would be hard not to join the chorus of dismissal if we didn’t know what kind of movie this was meant to be. The only person willing to lend any credence to Blair’s story is Karl the handyman (Ralph Penney— aka Cy Schindell— who spent most of his career playing hench-thugs in films like The Brute Man and The Monster and the Girl); he knows it’s possible for the living and the dead to communicate, because he talks to his mother’s spirit every week. If Julian wants, Karl can take him to see Blanche Walters (Anne Revere, from Secret Behind the Door and Dragonwyck), the medium who facilitates these conversations.

Normally, Blair would be disinclined to credit spiritualism, but in light of his recent experience, his own research might be taken to support it in a sense. After all, if the brain transmits electromagnetic impulses, why shouldn’t it also be capable of receiving them? And if the dead are transmitting strongly enough for the encephalograph to read them, why shouldn’t a living brain be able to pick up those signals, too? Blair’s visit to Mrs. Walters is disappointing on the surface, for she turns out to be a charlatan in the tradition of Paul Bavian and Rosemary LaGrange, but closer investigation suggests that the doctor might not have wasted his time on her after all. Blair easily finds and exposes the hidden speakers and projectors whereby Walters fakes her spirit manifestations, but he sees no obvious way to explain the electrical current that shot through the circle of suckers from hand to hand during the séance. Walters (who at this point has no more reason not to come clean about anything) says she doesn’t use any electroshock trickery, which Blair takes to mean that the current he felt must have been a legitimate product of the medium’s nervous system. That would make hers the most electrically powerful brain that Julian has ever encountered— powerful enough, perhaps, to serve as an amplifier for a modified version of his encephalograph. The first experiment along those lines shows great promise, especially after Julian adds Karl to the amplification circuit. Unfortunately, however, Karl does not have Blanche’s electromagnetic stamina, and the feedback reduces him to little more than a human vegetable.

Now that she understands both what Blair is trying to do and that he might actually be capable of succeeding, Walters begins looking ahead to the wealth and power that such success could bestow upon anyone wily enough and ruthless enough to exploit it properly. Blair, in contrast, remains monomaniacally fixated upon talking to his wife, and the combination of that blinkered vision and the doctor’s native guilelessness gives Walters an opening to become the senior partner in their project. She’s the one who finds the remote New England mansion to which the pair retreat to carry on their work in isolation and secrecy. She’s the one who pushes Julian to grave-robbing when it turns out that a dead brain can boost her telepathic power almost as well as a live one. She’s the one who manages all the household affairs, engaging the scrupulously incurious Mrs. Marcy (Dorothy Adams) as housekeeper, interposing herself between Blair and any of the locals who might wish to see him, and intercepting all the mail either leaving or entering the house so as to prevent any communication between the doctor and his former associates— including and especially Anne. The trouble with all this carefully orchestrated sneakery is that country people are severely allergic to it, and Walters soon finds herself contending with Sheriff Ed Willis (The Monster and the Ape’s Kenneth MacDonald), who feels himself compelled to investigate rumors of a connection between Blair and the five fresh corpses that have gone missing from their graves in the two years since the doctor and his scheming muse came to town. Willis eventually succeeds in suborning Mrs. Marcy to act as his spy, but the maid’s snooping gets her killed when she finds what the sheriff is looking for. Blanche is able to engineer a plausible-looking accident to account for the woman’s death, but Mr. Marcy (Walter Baldwin, of Rosemary’s Baby and All that Money Can Buy) is not persuaded by her ruse.

Looking over the preceding synopsis, I begin to suspect that I’ve made The Devil Commands sound fucking awesome, and by all rights, it really ought to be. It has a very canny script that puts all manner of wizened clichés to new and imaginative uses. It has a terrific villain in Blanche Walters, a sham medium who turns out to be convertible to the real thing with the aid of a little mad science, and Karloff’s authentically raddled performance makes Julian Blair the most sympathetic of all the deranged doctors he played for Columbia. Even the production design is super-cool, with lab sets that owe more to Rotwang the inventor’s hideout in Metropolis than to the expected Frankenstein-inspired Strickfaddenisms. (Actually, what it reminds me of most is the dynamo set from Gold— which is also the dynamo set from The Magnetic Monster via the magic of stock footage— but I wouldn’t like to speculate on the likelihood of the people behind The Devil Commands ever having an opportunity to see Gold.) And yet in practice, The Devil Commands is only slightly less silly than any of Monogram’s contemporary horror films. So far as I can tell, virtually all of the blame for that may be laid at the feet of director Edward Dmytryk, who rarely lets slip a chance to undercut himself here. That’s a curious point in itself, for Dmytryk would mature into a quite well-respected filmmaker, especially in the field of film noir. This was an earlier phase in his career, though, a phase in which he mostly made unambitious schlock like Captive Wild Woman— which this film rather markedly resembles in tone and execution. The trouble is that The Devil Commands is extremely ambitious schlock instead, ill-served by such crass features as heavy-handed narration (even were it delivered by a much better actress than the virtually useless Amanda Duff, and were it not obviously ripped off from Rebecca for no sensible reason) or rioting mobs of angry villagers. Dmytryk’s Universalesque potboiler approach works against this movie’s best qualities, but only partially compensates by infusing it with endearing goofiness.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact