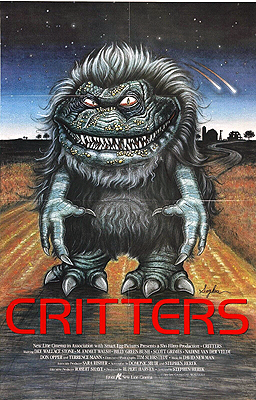

Critters (1986) ***½

Critters (1986) ***½

At about 11:00 PM on Sunday, August 21st, 1955, police in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, got one of the wildest calls for help they’d ever receive. Two carloads of frightened farm folk, led by Elmer “Lucky” Sutton, claimed to have spent the hours since 7:00 fighting off a determined attack by beings from outer space. Sutton and his companions described their assailants as gray-skinned humanoids between two and three feet tall, with huge heads, pointed ears, and lambent, widely-spaced eyes. Their legs were short and spindly, but their arms were long and strong, ending in webbed and taloned hands. And their clothing (if that’s what it was) was reflective, as if it were made of some metallic fabric. The incident began when Billy Ray Taylor, a friend of Lucky’s, and one of three people who had accompanied him on a visit to the old Sutton family homestead, observed what he believed was the landing of a large, metal object in one of the nearby fields. Taylor and Sutton were preparing to investigate when they were driven back into the house by the first of the creatures. What followed was a veritable siege of the farmhouse. Although the family were able to keep their foes out with the aid of a shotgun and a target pistol, any attempt to leave invited immediate attack. Bullets didn’t seem to harm the creatures, but they would retreat with a strange, silent levitating motion if struck. Eventually, there came a lull in the battle sufficient for Sutton and the others to make a break for it, which is how it became a matter for the Hopkinsville police. The cops found nothing at the scene but evidence of the defenders’ own gunfire. Whatever had so terrorized the occupants of the farmhouse that night, it had disappeared without a trace.

The legend of the Hopkinsville Goblins (as the press subsequently dubbed Lucky’s little, grey men) is one of my all-time favorite paranormal encounter stories, because it’s equally entertaining in each of its three most natural interpretations. Lucky and Billy Ray were both carnies, and Taylor apparently had something of a reputation as a prankster. So maybe the whole thing was an epic hoax perpetrated to liven up a dull night on the farm— one that succeeded so spectacularly that people are still talking about it 60 years later. On the other hand, Sutton’s description of the creatures bears some suspicious points of resemblance to the great horned owl, which is native to that part of Kentucky: two-foot height, big head with pointy ears and huge eyes, talons, spindly legs, capability for eerily silent flight. Great horned owls are furthermore quite ferocious in defense of their nests, especially if there are hatchlings in them. So what if we’re just talking about two half-tanked hillbillies going out to look at a low-flying meteor (several unconnected witnesses reported seeing shooting stars on the night in question), straying too close to an owl’s nest, and getting chased home by Mr. and Mrs. Great Horned? Or we could take the whole thing at face value, in which case we’ve got a nominally true spook story for the fucking ages.

Now if you do the latter, it isn’t long before you’re going, “Shit, man— somebody needs to make a movie about that,” is it? We almost got one out of Stephen Spielberg, of all people, as a sort of repost to his own Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It was to have been called Night Skies, but over the course of its development, the project split in two, and mutated into both E.T.: The Extraterrestrial and Poltergeist. Around the same time, though, another filmmaking Stephen by the surname Herek was working on a treatment for a picture of his own combining the Hopkinsville Goblins story with a childhood nightmare about being chased by rolling balls of fur and fangs. New Line Cinema bought the script that Herek eventually wrote with Domonic Muir, but proceeded to do nothing much with it for a couple years. Then Gremlins happened. Suddenly hordes of miniature monsters were the hot new thing, and Herek’s project was promoted several steps up the studio’s hierarchy of priorities. It emerged in 1986 as Critters, giving rise to a franchise that would persist until well into the 90’s.

Somewhere deep in space floats the prison asteroid overseen by Warden Zanti (Michael Lee Gogin, of Wacko and Munchies), apparently part of the correctional apparatus for an interstellar civilization of considerable diversity and extent. When we meet Zanti, his institution is taking delivery of a shipload of Crite prisoners. It’s never explained just what crime the Crites committed, but it seems safe to assume that it had something to do with their species’ habit of eating everything (and everyone) in sight. They must be really bad news, too, because Zanti has them scheduled for execution immediately upon reaching the prison. That isn’t what happens, though. Instead, the Crites overcome their guards and escape, stealing a starship with sufficient range to take them anywhere in the galaxy. As soon as he gets word of the breakout, Zanti calls in some outside contractors with whom he’s worked before, a pair of bounty hunters belonging to a versatile race who can shape their virtually amorphous flesh into the likeness of any approximately humanoid being. Although he admonishes the bounty hunters to be less wantonly destructive than they were on their last mission for him, Zanti also makes it perfectly clear that the extermination of the escaped Crites has absolute priority over all other considerations.

The Crites have chosen Earth as their destination, of course. After all, there’s plenty to eat here. But instead of jumping straight into their rampage of comestation, Critters pauses for a bit to familiarize us with the little rural community of Grover’s Bend, Kansas. We meet Harv the sheriff (M. Emmett Walsh, from Harry and the Hendersons and Sundown: The Vampire in Retreat), his rather hapless deputy, Jeff Barnes (Ethan Phillips, of Toolbox Murders 2 and The Island), and Sally (Lin Shaye, from My Demon Lover and Alone in the Dark), the short-tempered police dispatcher. We meet the smarmy Reverend Miller (Jeremy Morris) and Charlie McFadden (Android’s Don Keith Opper), the hard-drinking town loony. But mostly we get to know the Brown family: Jay (Billy Green Bush, of Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday and The Beasts Are on the Streets), Helen (Dee Wallace, from Cujo and The Frighteners), and their two children, April (Nadine Van Der Velde) and Brad (Scott Grimes). You’ve seen effectively this same bunch in a hundred other movies set in small-town America. Jay is the stern but loving patriarch, Helen is the completely useless housewife, April is the outwardly well-behaved favorite with a carefully concealed wild streak, and Brad is the put-upon pubescent troublemaker longing for parental approval that he can’t ever quite seem to earn. And in case this weren’t already obvious, the Browns are also this movie’s stand-ins for the Sutton clan.

The Browns’ first brush with the Crites is very indirect. Brad takes their stolen ship for a shooting star when it flies over the house, and the whole family experiences the vibrations of its engines upon landing as a mild earthquake. Those don’t happen in Kansas, so Jay is quick to make the connection between the two anomalous phenomena, guessing that Brad’s meteor must have crashed somewhere on the farm. The ensuing father-son investigation is cut short, however, when Jay and Brad come across the half-devoured carcass of one of their cows. Matters grow even more alarming when the power suddenly fails in the house. Descending into the basement to check the fuse box, Jay at last meets a Crite face to face. The aliens are a bit like the Tasmanian devil as imagined by the Warner Brothers cartoon studio. They stand about fifteen to twenty inches high, and their furry, almost spherical bodies are little more than support systems for their immense, toothy mouths. Although the Crites possess arms and legs, they make little use of the appendages, preferring instead to roll after their prey like killer tumbleweeds. And as if all that weren’t enough, they have crests of venomous quills down the centers of their foreheads, which they can shoot like blowgun darts to paralyze their victims. Jay is badly hurt, and April’s boyfriend, Steve (Billy Zane, of Back to the Future and Bloodrayne), is killed before the family are able to reach the relative safety of the house.

Meanwhile, Zanti’s bounty hunters are roaming all over Grover’s Bend, wreaking exactly the kind of havoc that the warden warned them against. Said havoc is rendered even more confusing and distressing to the folks on the receiving end by the guises the alien mercenaries adopt for going among the natives. One bounty hunter pulls the old broadcast-monitoring trick, and copies the face of poodle-rocker Johnny Steele (Terrence Mann, of Solarbabies) from a video on MTV. The other one gives the game away by changing faces every time he encounters somebody new. Consequently, when the reports of gun-toting crazoids start pouring in to swamp the increasingly flustered Sally at police headquarters, witnesses variously identify the puff-mulletted stranger’s companion as Charlie McFadden, the Reverend Miller, and even Jeff Barnes. Harv doesn’t know what to make of it until gunshots are reported coming from the direction of Brown’s Farm. That at least gives the sheriff an active lead to follow up. One fat cop probably won’t be much help against the Crites, but fortunately Harv won’t be alone in coming to the family’s aid. Brad is able to sneak past the besieging aliens, and the first people he meets on the road into town are the bounty hunters.

Critters is another movie that I saw and enjoyed in my earliest adolescence (I caught it in first run, when I was about twelve), but avoided subsequently for fear of disappointment. It’s also another case in which I needn’t have worried. Critters holds up remarkably well, confirming my memories of it as easily the best of the mid-80’s Gremlins cash-ins. Indeed, I’d rate it significantly higher than Gremlins itself, since Critters refrains from duplicating the latter movie’s catastrophic third-act implosion. That isn’t to say that Critters is without a silly streak; I mean, this film has its own version of the “monster in the toilet” gag from Ghoulies, alright? But Critters’ cartoon aspects are better integrated into the surrounding material, and proceed more naturally from plot points already established. For example, we’re cued nearly from the beginning to expect some humorous interplay between the aliens and the people of Grover’s Bend, since our introduction to Charlie catches him in the drunk tank, ranting to Harv about receiving transmissions from outer space via his dental fillings. So when the trigger-happy bounty hunters are played substantially for laughs, it comes across as a promise fulfilled instead of an irritating tonal digression. The character design for the Crites has a similar forewarning effect. Space criminals they may be, but rolling balls of fur with an ungovernable instinct to eat whatever is in front of their faces are obviously not meant to be taken entirely seriously. And just as importantly, Herek and Muir are consistent about how much seriousness is intended. The key tone-setting moment, I think, comes early in the siege of the Brown house. Having just seen Helen fire at them and miss with her husband’s shotgun, two of the Crites discuss this new development on the front porch. Subtitles helpfully translate the creatures’ chittering speech:

| Crite #1: “They have weapons.” |

| Crite #2: “So what?” |

| [Crite #1 explodes as Helen steadies herself and draws a bead on him.] |

| Crite #2: “FUCK!” |

Critters isn’t all just goofy fun, however. The Crites pose a genuine threat, and that threat is treated seriously even when the monsters themselves aren’t. Indeed, the incongruity between the creatures’ ugly-cute appearance and the savagery of which they’re capable is often the crux of the movie’s effectiveness. This is easiest to see in the scene where April and Steve are attacked in the hayloft to which they’ve surreptitiously retreated to be alone together. The Crites’ absurd body form is easier to make out than it was in the dark of the basement, making it simultaneously funny and horrid when they devour Steve. Then when Brad comes to his sister’s rescue wielding one of the supercharged firecrackers he’s been forbidden to have like an improvised hand grenade, one of the Crites eats it, inflates noticeably as it detonates internally, and then keels over dead. It’s as if the monsters on “The Muppet Show” were actually, you know, monsters.

Another thing that impresses me about Critters is its resistance to both of the diseases endemic to films with this kind of setting. On the one hand, it never succumbs to sentimentality, even though it’s primarily about a farm family whose greatest strengths lie in their old-timey country values, and on the other, it never reduces the people of Grover’s Bend to hackneyed redneck caricatures, despite their being the biggest bunch of tiny-town eccentrics this side of Perfection, Arizona. The first half of that is easier to account for, if perhaps also rarer to see done. When I say that the Brown family’s old-timey country values are their greatest strength, I mean that that’s something we’re shown, not merely something that’s told to us on their behalf. Again and again during the Crites’ attack, family loyalty, self-reliance, mutual responsibility, and trust in Jay’s leadership enable the Browns to survive, and to keep the invading aliens sufficiently off balance to counteract their numerical and physical advantages. As for the other half, it wasn’t for nothing that I referenced Tremors just now. Critters is like that movie in that its wacky townspeople are allowed to be a great deal more than wacky. Their personal oddities are shown to affect their lives and relationships, and not always in ways that are positive or even charming. Herek acknowledges how exhausting it must be for Jeff and Sally to work together, what a sad waste of a life it was when Charlie descended into drunkenness and delusion, how stifling an environment the isolated little town represents for a bright and self-willed girl like April. The result is that Grover’s Bend feels real, vital, and honest, in much the same way (albeit perhaps not quite to the same extent) as Perfection. It can’t be overstated how important that is in a film where the antagonists are a pack of hairy little eating machines that roll head over heels where other interstellar menaces would prefer to walk.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact