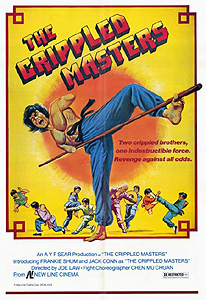

The Crippled Masters/Tian Can Di Que (1979/1982) -****

The Crippled Masters/Tian Can Di Que (1979/1982) -****

Every once in a while, you come across a film that seems to have been expressly designed to say, “And this, ladies and gentlemen, is why we call them exploitation movies.” These pictures go beyond sex, beyond gore, beyond impiety or disrespect for authority— indeed, beyond any conventional form of bad taste— to leave the viewer in slack-jawed stupefaction at the fact that their creation was ever seriously considered, let alone brought to full fruition. Tucked away in the middle of Taiwanese director Kei Law’s otherwise rather unassuming filmography is one such movie, apparently an attempt to cash in on the success of the Venom Mob vehicle Crippled Avengers, known in the English-speaking world as The Crippled Masters. The Crippled Masters might usefully be thought of as the Freaks of Chinese martial arts cinema, with the caveat that it really is as sleazy and disreputable as the old Tod Browning movie’s ad campaign misleadingly implied. Whereas the Venoms (or, for that matter, Jimmy Wang Yu in the One-Armed Swordsman and One-Armed Boxer movies) were merely playing crippled, The Crippled Masters casts as its heroes two men who suffered from profound birth defects. The reality of those absent or withered appendages, and of the things the stars are able to do anyway, is what makes this film simultaneously such a queasy viewing experience and so utterly fucking amazing.

In some vaguely defined bygone era (someone with a firmer grasp of Chinese history than I lay claim to might be able to pin it down by the costumes, but there’s no other clue that I can detect), a smallish town is beset by the tyranny of Master Lin Chang Cao (Li Chung Chien, from Immortal Warriors and Invincible Kung Fu Trio). When we meet Lin, he is specifically besetting a peasant by the name of Li Ho, although what exactly Li Ho did to get on Lin’s bad side is far from clear. Whatever the peasant’s transgression, the punishment for it is wildly excessive; Lin has one of his flunkies, a small but very muscular man called Tang, hack off both of Li Ho’s arms with a sword, after which several more flunkies eject him from Lin’s palace. (Li Ho and Tang are played by Frankie Shum and Jack Conn, both of whom went on to similar roles in Two Crippled Heroes and Fighting Life. The consensus of speculation seems to be that Shum plays Li Ho while Conn plays Tang, but nothing in the English-language version of The Crippled Masters particularly indicates which man is which.)

How Li Ho avoids bleeding to death within minutes is anybody’s guess, as he neither receives nor indeed seeks any sort of medical attention. He just staggers straight into town to launch a new career as a much shat-upon beggar, eventually getting booted out of a restaurant for putting the other customers off their lunches. The bouncer (Boon Saam, from Avenging Boxer and The Twelve Fairies) who does the rousting leaves Li Ho so badly mauled that he is mistaken for a corpse, and he gets picked up by Mr. Chin, the local coffin manufacturer (who might be played by Tai Leung, of The One-Legged Fiend and The Guy with Secret Kung Fu— there are two old men in this cast who look very much alike). This is a pretty bad deal for Li Ho, even if Chin does give him some food and a place to crash, because the biggest buyer of coffins in this town is none other than Lin Chang Cao, whose activities strangely have a way of producing lots of dead bodies. Pao (Hsiang Mei Lung, from Kung Fu of Eight Drunkards and Jade Fox), Lin’s right-hand sycophant, swings by to place an order, accompanied by one thug with an inexplicable gray face (Cheung Chung Kwai, from Shaolin Iron Claws and The Fatal Flying Guillotines) and another with an equally inexplicable gigantic and invulnerable head (Ma Cheung, of Fearless Hyena and The Killer Meteors). As soon as Pao sees Li Ho in the coffin shop, he orders his two leg-breakers to kill cripple and shopkeeper alike; Pao calls off the henchmen only when Chin poses the question of who will keep Master Lin supplied with caskets if he dies. Temporarily reprieved, Li Ho flees to the countryside for a life of misery made slightly less abject by the absence of anybody actively seeking to kill him. Eventually, he gets taken in by a peasant, which isn’t nearly as good a deal as it sounds, seeing as this great humanitarian expects the armless Li Ho to earn his keep as a farmhand. Oh well— at least having to water crops and whatnot forces Li Ho to become reasonably good at using his feet, jaws, chin, and the tiny stump of arm left to him by Tang (obviously really a congenital deformity) to perform the tasks he would once have carried out with his hands.

Meanwhile, Lin and his minions rough up an antique dealer who is late on the rent for his stall in the marketplace, take over a school (the headmaster of which is the other old guy who might be Tai Leung) in order to turn it into a gambling casino, and melt Tang’s legs away to useless streamers of skin and bone with a tiny flask of acid that somehow contains about six or seven gallons of the deadly potion. Evidently Lin has decided that Tang has been privy to too many of his secrets— although how he figures rendering the ex-flunky paraplegic is going to stop him from letting the skeletons out of the closet is a mystery to me. Tang, too, wanders off into the sticks, and as Fate would have it, he makes his way to the very farm where Li Ho has been working. Naturally, Li Ho recognizes the man who crippled him, and immediately makes with the ass-kicking— by which I of course mean literal kicking, as the poor man has nothing but one twisted little chicken-wing thing by way of an arm thanks to Tang. That’s when the shriveled old kung fu master speaks up from inside the wicker basket where he’s apparently been hiding out for the last… well, who the fuck knows, really? Even the Hong Kong Movie Database has no idea who this guy is (which is a shame, ‘cause he’s an absolute delight), but once Li Ho and Tang help him unknot himself from his X-Treme Lotus Position, the old man scolds the two enemies into making friends, and offers to teach them both kung fu so that they might take revenge on their true, mutual enemy, Master Lin. If you’ve ever seen a kung fu movie, you’ve seen the essentials of the next reel or thereabouts, except for the fact that the men undergoing the torturous training each have about a 50% shortfall in the functioning limbs department. Whether that makes the whole thing more interesting is open to debate, but it sure as hell makes it more uncomfortable to watch.

Once Li Ho and Tang have more or less earned their claim to the title of the film, the first thing they do is to drop in at that restaurant that Li got booted out of earlier. Let’s just say that the bouncer and his employers are not prepared to handle this eventuality. Equally unprepared are Pao, Bighead, and Grayface, who get themselves ambushed by the Crippled Masters while in the midst of springing their own ambush on some jewel thieves. (The operative theory here seems to be that no one is allowed to steal on Master Lin’s turf unless they work for Master Lin.) The bruisers are killed with remarkable dispatch, and Pao is sent packing in considerable humiliation. Luckily for Pao and Lin— well, maybe luckily, anyway— there’s a new arrival in town by the name of Ho (Chan Muk Chuen, of Lady Snake Fist and The Iron Monkey), who doesn’t seem to do much except lounge shiftlessly about and occasionally kung fu the living shit out of somebody who tries to mess with him. Lin is initially concerned about the disruptions Ho could cause to the local power structure, but Pao thinks he could actually be very useful. If Lin put Ho on the payroll, he’d have a replacement for Bighead and Grayface who might plausibly be a match for the two avenging cripples. A demonstration of Ho’s fighting prowess convinces the arch-villain, and Ho goes from layabout to chief bodyguard in one easy step.

This is where things start to get complicated. The Crippled Masters’ unnamed sifu knows Lin Chang Cao from way back, you see. Years and years ago, the old man discovered a set of eight jade horses, which had been sculpted so as to encode the secrets of some incredibly powerful fighting technique. Lin stole this treasure, however, before its kinda-sorta-rightful owner could crack the code. With the sifu’s help, and at his instigation, Li Ho and Tang infiltrate Lin’s palace to counter-burgle the jade horses, and only Ho has the competence to stand in their way. What he does not have, as he reveals after a short skirmish with the cripples, is any intention of actually doing so. Ho, it turns out, is really an agent of the provincial government, sent to reign in Lin’s abuses. What Ho didn’t figure on was Lin’s own fighting ability, which outclasses that of everyone we’ve seen in action thus far. In particular, it seems that the hunch on Lin’s back (which constantly changes size and shape throughout the movie, much like the huge, blackened scar on his face) is an invulnerable super-hunch, making it pointless to attack him from behind, even as his mastery of ass-kicking makes it too dangerous to attack him head on. No bonus points for guessing that the techniques revealed by the eight jade horses are the key to overcoming Master Lin, and no bonus points, either, for guessing that The Crippled Masters comes to an immediate and dramatically unsatisfactory halt the instant the final blow of the showdown is landed.

It takes a lot of moxie— arguably more moxie than any human should be able to muster— to make a movie like The Crippled Masters. This is a freak-tent picture, pure and simple, and it displays not the slightest suggestion of shame about it. The closest thing this movie offers to a redeeming feature is that it’s legitimately amazing what Frankie Shum and Jack Conn are able to do in spite of their disabilities. As impressive as Johnny Eck’s no-legged agility was, he had absolutely nothing on Conn (or maybe Shum), whom we see run, jump, climb ropes, and (obviously) perform kung fu despite being not just paraplegic, but also hampered by a rather substantial pair of vestigial legs, which he generally keeps folded up in a lotus position underneath his similarly vestigial butt. Shum (or maybe Conn) is in some ways even more impressive. Although the bamboo staff he wields in two scenes is obviously much thinner and lighter than a standard bo, he’s still twirling a goddamned staff with a goddamned chicken-wing flipper-arm! It’s a feat of dexterity that most of the people watching The Crippled Masters couldn’t duplicate with two normally formed upper limbs. I can’t begin to imagine the training that must have gone into Shum’s and Conn’s performances, and they sure as shit deserved any fame, money, or success that might have come their way as a result of the handful of films they made together in the late 70’s and early 80’s.

Otherwise, The Crippled Masters is composed of roughly equal parts sleaze and idiocy. The sleaze all comes in the form of variations on the cripsploitation theme, and isn’t much worth a detailed discussion. The idiocy, on the other hand, is of a truly fine grade, and bears looking at more closely. If you’re the kind of person who demands to have things explained, or indeed to have them make any kind of logical sense at all, The Crippled Masters is absolutely not the movie for you. What’s the deal with Lin Chang Cao’s hunch, or with his two top thugs’ comparable physical peculiarities? And for that matter, why does Grayface seem to derive no special powers or abilities from his abnormality when Lin’s and Bighead’s both confer immunity to some specific form of attack? Don’t ask me— it never comes up. Why was the Basket Sifu in a basket, why did he pick that particular barn to be his hermitage, and how did the owner of the farm fail to notice his presence for its unstated but implicitly lengthy duration? That never comes up, either. Ho seems to exist for no other reason than that cliché demands it, for he certainly never performs any function that couldn’t have been handled equally well by another character. And speaking of cliché, I got a big kick out of the “Master Lin takes over a school to use it as a casino” scene— it has little to do with anything, but what self-respecting kung fu movie villain doesn’t try to help himself to somebody else’s school at some point? Chin the coffin-maker falls right out of the story so quickly that you wonder why he was included in the first place, and the beat-down he receives from Pao and the leg-breakers is a mystifying turn of events, stemming as it does from so slender a motive. Whether such amusements make you feel better or worse about watching one of the world’s few genuine cripsploitation movies is a matter of temperament, I suppose, but it certainly worked for me. Then again, we didn’t need The Crippled Masters to demonstrate that it was going to be, “Go directly to Hell. Do not pass ‘GO;’ do not collect 72 virgins” for me, now did we?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact