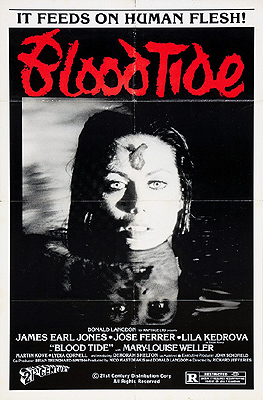

Blood Tide / Bloodtide / Demon Island / To Kyma tou Aimatos (1982) **Ĺ

Blood Tide / Bloodtide / Demon Island / To Kyma tou Aimatos (1982) **Ĺ

Oftentimes when Iím grinding my gears on a review that doesnít want to be written, Iíll try to snap out of my paralysis by taking on some junky cheap thing selected almost at random. Just about anything will do, so long as it looks formulaic enough to write about using only the shallows of my brain while my subconscious attacks whatever problem is thwarting me in reviewing the other film. Itís a sound strategy, and it usually works just fine. Occasionally, however, I outsmart myself by accidentally picking something with unexpected conceptual heft to it. Something still cheap and junky, and maybe not be especially good, either, but something that rewards close attention and serious thought nontheless. Thatís what I got myself into with Blood Tide. This Greco-British obscurity looks from a distance like a monster flick of little accountó and if you try to watch it in that frame of mind, youíll probably be disappointed, because the monster is just barely in it. But if you approach it instead as The Wicker Manís impoverished Aegean cousin, you may find much more in Blood Tide to appreciate.

3000 years ago, when civilization was first asserting itself in the territory now known as Greece, inhabitants of the isle of Sinarron had a more hands-on relationship with the gods than comes of roasting bulls on barbecue altars or wrestling for laurel crowns with oneís dork hanging out. The islanders worshipped the weird-ass horse-headed gill man that dwelled in one the sea caves along their coastline, and kept it happy by sending it a virgin every now and again. They maintained their practice of human sacrifice in the face of competition from more respectable Olympian religion, but things changed when Christianity came to Sinarron. Gill man worship was suppressed, the creatureís lair was walled up, and a convent was built on the island dedicated to Saint Cosimas, whose iconography depicted him overthrowing the virgin-despoiling fiend.

That brings us to 1982, when freelance photographer Neill Grice (Martin Kove, from Future Shock and The White Buffalo) and his wife, Sherry (Mary Louise Waller, of The Evil and Q), arrive on Sinarron by cabin cruiser. This isnít a business trip for Neill, no matter how photogenic the scenery might be, nor is it a romantic boating vacation. Rather, the couple have come to search for Neillís sister, Madeline (Deborah Shelton, from Body Double and Ultimate Desire). An artist herself, Madeline came to Sinarron months ago to do restoration work on the religious paintings in the convent, and hasnít been heard from since. The reception the Grices get from the locals isnít hostile, exactly, but it isnít friendly either, and Nereus the village headman (Jose Ferrer, of Bloody Birthday and Draculaís Dog) makes it as clear as he can without resorting to hostility that he wants them to get the fuck off of his island posthaste.

Yeah, well Neill isnít going anywhere until he at least knows what happened to his sister. The following morning, he and Sherry pay a visit to the convent, which is where they probably should have started anyway. Sister Anne (Lila Kedrova, from Sword of the Valiant and Night Child), Madelineís closest friend among the nuns, is no more cooperative than Nereus, but itís obvious that the missing girl was on the premises quite recently. Her restoration gear is still set up in an easily accessible room, in such a way as to suggest that she had just begun work on a Renaissance-era painting of (would you look at that?) a warrior saint vanquishing a sea demon. Knowing now that heís on the right track, Neill becomes even more stubborn about sticking around. His obstinacy is rewarded that evening, too, when he spots Madeline through the windows of a shack by the docks. At first, Neill leaps to the conclusion that the man in there with her is her kidnapper, but it turns out that Madeline and Frye (James Earl Jones, of Terrorgram and Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb) are in fact close yet recent friends. He and his girlfriend, Barbara (Lydia Cornell), are treasure hunters, and Madeline has them convinced that thereís something interesting (which to them means something valuable) in a sea cave at the foot of the cliffs below the Saint Cosimas convent.

Madeline is right, of course, but as Iím sure youíve already guessed, not everything hidden in that cave is susceptible to being flipped on the international antiques market. It was the custom during Minoan times for sacrifices to the gill man to be given a single silver coin with which to pay for their passage to the Underworld after the monster was finished with them. Since gill men neither shop nor pay rent, those centuriesí worth of ancient obols are still scattered all over the mostly submerged floor of the cave. Frye has already found a slew of the coins, but since he knows nothing of how they got there, he plausibly assumes that the real prize is whatever lies entombed behind the obviously man-made wall at the back the cavern. He came to Sinarron as well prepared as any Boy Scout, too, so millennia-old masonry is no more than a temporary impediment to his search. Frye doesnít even need the whole brick of plastique to blast right through. You can imagine how flummoxed the treasure hunters are to find that thereís nothing back there after all but another disorderly cache of the same old silver coins. Not long after Frye knocks down the wall, though, strange things start happening on and around the island.

First, a teenaged girl disappears while swimming in the cove beneath the cliffs. Opinion in the village initially favors the theory that she was kidnapped or worse by one pair of foreigners or the other, but after a day or two of rising tension, her corpse washes ashore in a condition that plainly exonerates Frye, Barbara, and the Grices. No human could mangle another like that without, letís say, specialized equipment. Nereus begins warning darkly of a man-eating shark in the waters where the outsiders have been spending most of their time since reconnecting with Madeline, but they all know the Aegean well enough by now to recognize that itís ecologically incapable of supporting sharks of any species large enough to threaten a person. And since the old man always couches his shark talk as a reason for them to pack up and leave, it sounds like yet another attempt at an obscurely motivated cover-up. Frye himself sees some large living creature in the water soon thereafter, and although he has no idea what it is, itís certainly no shark. Next, the local children start acting peculiar, ganging up on one girl in particular to pester her in ways that visibly frighten her mother. The supposed shark victimís funeral takes a bizarrely pagan turn, much to Sister Anneís horror. And speaking of things that horrify Sister Anne, Madelineís increasingly obsessive work on the icon of Saint Cosimas reveals that the Renaissance image was overlaid atop an earlier, more Byzantine-looking interpretation of the same scene, in which the saint seems markedly less triumphant, and the sea demon markedly more menacing. Madeline is sure, too, that thereís yet a third painting hidden beneath the second one, but the nun implores her to leave it be, for the sake of her eternal soul. Meanwhile, the men of the village are putting together a festival that hasnít been celebrated on Sinarron in some 1500 years. It isnít just that Fryeís treasure hunt has turned loose a monster, you see. The forces unleashed by the outsidersí meddling are pushing the islandís culture backwards toward Minoan barbarism on pretty much every front.

I wonít argue that Blood Tide isnít an extremely minor film, or even that itís especially ripe for rediscovery. No, the people who keep slipping it into public-domain DVD box sets have found its natural level. That, after all, is one of the nearest modern equivalents to the extinct experience of stumbling upon some forgotten oddity on late-night television, and having it lodge in your brain in fragments that leave you unsure you didnít just dream the whole thing. This is very much that sort of film. But the next time youíre in a mood to tolerate something messy, something unsettled, maybe even something that doesnít quite feel finished, but which youíll nevertheless find yourself thinking about again and again at odd moments over the ensuing days, Blood Tide fits the bill rather well.

Its most immediately obvious strength is how it uses the Greek setting to create a mood that is both like and unlike The Wicker Man. Most of what people nowadays call ďfolk horrorĒ (a term which I find unsatisfactory in its current usage for a host of reasons, but thatís a topic for another time) has a very specific set of Northern European cultural associations. Itís all about isolated farming communities and seasonal rhythms and harvest festivals with deep pagan roots. None of those signifiers are relevant to an Aegean island where people are crowded together into a tiny urban center thousands of years old, earning their living from the sea in a place that barely even has seasons as the upper half of Europe knows them. And although Blood Tide recapitulates The Wicker Manís conflict between conservative Christianity and a resurrected paganism, it draws the battle lines across Sinarron itself, with the outsiders (none of whom appear to have any religious convictions as such) positioned as onlookers with no direct stake in the outcome, but every chance of becoming collateral casualties. The latter distinction with The Wicker Man has a downside as well as an upside, however, insofar as the filmmakers seem not to have realized that the question of whether Our Heroes have accidentally brought the old gods out of retirement to stay is considerably more interesting than whether or not they can kill a monster and go home. But the main source of power that the film draws from its setting is the sheer weight of history, symbolized most evocatively by the multi-layered icon of Saint Cosimas. Madelineís work on the painting functions almost as a form of possession (I imagine many artists will find that relatable even without reference to immortal gill men), and the eventual revelation of the primordial version of the image is a genuine shock coming from a movie made at least partly by Brits.

The other thing about Blood Tide thatís sure to jump right out at you is James Earl Jones acting the shit out of what most other performers would have treated as an inconsequential paycheck role. I gather that there was a lot of improvisation in his performance, or alternately that Fryeís lines were extensively rewritten when Jones got the part, because one of the characterís eccentricities is that he, like the man playing him, was a Shakespearean actor before he got into treasure hunting. Fryeís dialogue is heavily peppered with quotes from Othello, which Jones himself had just finished starring in for the second time when the shooting for Blood Tide got underway. Itís wild hearing bursts of iambic pentameter come booming out of a smalltime crookís mouth in Darth Vaderís voice every few minutes, and thatís only Fryeís most readily describable eccentricity. The cast is surprisingly effective all around (even Martin Kove does solid, journeyman work here!), but Jones just folds the whole movie up, and tucks it into his pocket.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact