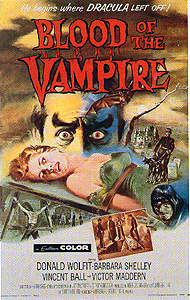

Blood of the Vampire (1958) **½

Blood of the Vampire (1958) **½

One of the problems with watching as many movies as I do is that it becomes increasingly difficult to be sure when an apparent connection between two films is real, and when it’s just a remarkable coincidence. The more comparatively obscure flicks I see, the more often I encounter scenes, characters, plot devices, etc. that make me sit up and go, “Hey! That’s just like [fill in the blank with the title of some other, usually much more famous film]!” and the more often that happens, the harder it becomes to judge whether the filmmakers really are cribbing each other’s ideas or whether they independently decided it would be cool to do whatever it was that made me suspect a connection. For instance, we may be reasonably certain that Dan O’Bannon and/or Ridley Scott saw Planet of the Vampires before getting to work on Alien. It seems pretty likely that Invisible Invaders crossed George Romero’s mind on more than one occasion while he was writing and filming Night of the Living Dead. And no matter what he may say to the contrary, there’s just no way in hell Steve Miner thought of that pin-the-screwing-teenagers-to-the-bed-with-a-spear set-piece in Friday the 13th, Part 2 independently of Twitch of the Death Nerve. On the other hand, I think we can probably discount the claims I’ve heard a few fans of Italian horror make (in all seriousness, mind you) that John Boorman’s The Emerald Forest is really an uncredited remake of Umberto Lenzi’s similarly titled cannibal gut-muncher, The Emerald Jungle. But what are we to make of something like Blood of the Vampire, in which a skunk-haired mad doctor is raised from death by technological means only to become a sadistic killer who needs other people’s blood to preserve his own unnatural life? Can it truly be that the folks at Tempean Studios were consciously creating a gothic remake of The Return of Doctor X?!

You wouldn’t even think to ask such a question on the basis of the opening scene. Blood of the Vampire’s pre-credits sequence would be right at home in any purely conventional vampire flick. After a voice-over lecture explaining (as if anyone could really be in ignorance of such things by 1958) just what a vampire is, we are shown the familiar scene of backward, mid-19th-century Central European churchmen burying a suspect body, and driving a stake through its heart. (There is one noteworthy departure from form here, though. Note the vast length of the stake. Not only does this allow the men doing the dirty work to handle the whole operation without climbing into the grave, it also plays up the original purpose of the stake in medieval folklore: to keep the vampire fastened securely to the ground and thereby confine it to its tomb.) But after the credits have rolled and the vampire killers have gone home, a mute hunchback with a bad eye (Victor Maddern, of Psycho-Circus and The Lost Continent) digs up the grave and makes off with the body (Donald Wolfit, from Satellite in the Sky and the 1961 version of The Hands of Orlac, made up to look remarkably like a cross between a gone-to-seed Bela Lugosi and Humphrey Bogart in The Return of Doctor X). Carl the hunchback takes the perforated corpse to the home of a besotted and easily blackmailed doctor, with instructions (apparently from the supposed vampire himself) on how to revive it by means of a heart transplant. Once the operation is completed, though, the doctor starts pestering Carl for more money, and the hunchback introduces him to the sharp end of the dirk he keeps in his coat pocket.

Some years later, another doctor by the name of John Pierre (Vincent Bell) is on trial for malpractice; evidently he was trying (without a lot of success) to preserve a patient’s life by the most unorthodox means of injecting him with another man’s blood. The case takes a sharp turn against Pierre when the court receives a letter from his mentor, Dr. Meister (on whom John was relying as an expert witness on his behalf), asserting that he has never heard of the young doctor in his life! Pierre is found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Oddly enough, though, Pierre spends very little time at the institution to which he was condemned, but is transferred instead to an asylum for the criminally insane under the direction of a certain Dr. Callistratus.

Callistratus. “Beautiful sky.” A pretty good name for a pocket Mengele if you ask me, but if anybody in this movie appreciates the irony, it goes unremarked. The typically brutal head guardsman, Wetzler (Andrew Faulds, from The Devils and The Crawling Eye), locks Pierre up in a cell with a prisoner named Kurt Urach (The Shuttered Room’s William Devlin), and it is from Urach that our hero first gets some idea of how much trouble he’s fallen into. It isn’t just that the regime at the prison/asylum is harsh, or that there is no real hope for someone confined unjustly to make his voice heard, but that Callistratus himself has some kind of ongoing project that consumes the lives of his inmates at an alarming rate. If ever Wetzler or one of his men comes to collect you for an audience with the doctor, you can pretty much forget about anyone ever seeing you again.

So would you care to guess what happens to Pierre on his very first day at his new home? That’s right, he gets called in to see the boss-man. And considering the fact that the man who shows Pierre to the laboratory is none other than Hunchback Carl, I bet you won’t be too surprised, either, when Callistratus turns out to be the man who was executed as a vampire back before the credits. The doctor reveals that Pierre is indeed going to play a role in his secret research, but not, as Urach has led him to fear, as a guinea pig. Callistratus needs an assistant, and it is for that reason that he arranged to have Pierre moved to his asylum. Nor is it just because Pierre is a fellow doctor that Callistratus has taken an interest in him. Callistratus knows all about the reason why John was sent to prison, and contrary to the opinion of the court, he believes that blood transfusions hold great promise as a technique of modern medicine— indeed, we will later learn that it was his transfusion experiments that gave his neighbors the idea that the doctor was a vampire in the first place. But his research has determined that there are several distinct types of human blood, and that blood samples of different types often react antagonistically when mixed. What Callistratus wants from Pierre is his help in isolating and cataloging all of the different human blood groups, with the ultimate aim of using this knowledge to treat an extremely rare— but also extremely deadly— condition of the blood. (No bonus points for guessing either that Callistratus suffers from this mysterious condition himself, or that the only way to treat its symptoms is get frequent, large-scale transfusions from people who don’t.) In exchange for his cooperation, Pierre will have the run of the prison, and will be excused from the sort of manual drudgery that so defines his fellow inmates’ existence. Faced with an opportunity to be a doctor again, Pierre signs on to Callistratus’s project.

Meanwhile, out in the world, Pierre’s fiancee, Madeleine Duval (Barbara Shelley, from Cat Girl and Dracula, Prince of Darkness), is looking for ways to spring him from the pokey. She was just as stunned as her boyfriend to hear about Meister’s disavowal of him, and immediately rushed off to Vienna to ask the old man what his fucking problem was. In doing so, she discovered not only that Meister (The Giant Behemoth’s Henry Vidon) didn’t write that letter to the court, but that Pierre’s letter requesting his aid as a witness never even reached him— hell, this is the first Meister’s heard that his old pupil was in any kind of trouble! Taking the professor before the commissioner of prisons (Colin Tapley, from Paranoiac and The Black Room), Madeleine makes a convincing enough case that the commissioner orders his right-hand man, Herr Auron (The Hand's Bryan Coleman), to reopen Pierre’s file and commence a thorough investigation.

Unfortunately for Pierre, Auron has been on the take from Callistratus for years. In fact, it was Auron that intercepted Pierre’s letter to Dr. Meister and forged the letter from Meister to the court, all so that the resurrected mad doctor could get his hands on an assistant whose scientific thinking was as radical as his own. Now in order to keep him, the two conspirators are going to have to see to it that Pierre disappears permanently off the prison commission’s radar, and what better way to do so than by faking his death? Urach, you see, has what he believes is a near-foolproof escape plan, but carrying it out will require two people. When Pierre (who has begun to believe the dire stories the other inmates— insane or not— tell about his new boss) agrees to join him in the jailbreak, Callistratus proves too clever an adversary by far. He’s known all along what Urach had in store, and the doctor has rigged the situation such that the escape attempt fails and Urach is killed in his dash to the prison’s outer wall. Then when the story gets out, Callistratus edits the tale to include the death of John Pierre as well. And just when the commissioner of prisons had decided to order the man’s release, too…

Madeleine Duval, however, still thinks she smells a rat. No sooner has she heard of her fiance’s demise than she arranges to take a job as Callistratus’s domestic; from her new vantage point within the asylum, she should have no trouble getting to the bottom of everything. Sure enough, she runs across Pierre within hours of her arrival on the premises, but there’s one thing Madeleine hasn’t figured on. Auron knows her from her frequent appearances at the office of his boss, and because he spends a lot of time hanging out at Callistratus’s place, he’s sure to bump into Miss Duval sooner or later. And when that happens— well, let’s just say Madeleine’s going to acquire some firsthand insight into why her new job has such a high turnover rate.

You don’t know how hard it is to resist the temptation to describe this movie as being “a trifle anemic.” Nevertheless, I’ve seen far worse 50’s-vintage British horror flicks than Blood of the Vampire. Some viewers will probably be put off by the fact that the movie features none of the traditional vampire trappings beyond the original execution by staking of Dr. Callistratus, but I for one don’t mind that at all. I do wish that a bit more had been made of the doctor’s need for other people’s blood, and it irks me slightly that much of the unholy research he carries on down in the asylum basement bears no apparent connection to its supposed aims, but in general, this film is nowhere near as stupid as its likely antecedent, The Return of Doctor X. Most importantly, Blood of the Vampire is surprisingly unapologetic in its gruesomeness, considering how famously squeamish about such things producers Monty Berman and Robert S. Baker were. There may not be much here that will shock a modern audience, but in 1958— especially in England— Callistratus’s ghoulish experiments were pretty strong stuff.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact